The capital markets union: Should the EU shut out the City of London?

- London is home to Europe’s biggest capital market. Brexit poses significant policy questions for the EU-27 as to how capital market activity should be managed and regulated once the UK has left the EU.

- The EU’s ambition is to create an ‘onshore’ capital market within the Union, and this has become the focus of the capital markets union (CMU) project since Britain voted to leave. The CMU project, which has been going since 2014, aims to create a deeper, more integrated market for cross-border financing and investments within the EU. The ambition is laudable: deeper integration of capital markets could make the European economy more stable, more effectively channel funding to the best investments, and give investors and firms more options.

- However, progress was slow even before Brexit. Integration of capital markets requires changes to many different areas of policy, including business and financial law, taxation, accounting and insolvency regimes.

- The UK’s imminent departure probably ends the prospect of the development of a global-scale capital market within the EU. This raises a fundamental question for the Union: how integrated into global capital markets does the EU want its domestic capital markets to be?

- Continental European capital markets are small, relative to the US, because EU industry is overwhelmingly reliant on banks for finance. While some argue that the banking model of corporate financing is appropriate for European business, global pressure on bank balance-sheets suggests that banks alone are insufficient to fully finance growth. Companies will increasingly be forced to look for financing elsewhere.

- With the UK leaving, Europe’s major hub of non-bank capital will soon be outside the EU’s regulatory purview. The EU will need to decide whether to keep London at arm’s length while pursuing an inward-looking strategy, or instead open up its market to London and the rest of the world.

- This dilemma poses a fundamental policy challenge for the EU. Deeper integration with the UK and the rest of the world would increase European businesses’ access to international capital and could boost European growth. However, deeper integration might also result in a loss of EU regulatory control, given the relatively small size of EU markets compared to New York and London: European corporates could continue to seek finance outside the Union as a result.

- For the UK, the concomitant policy challenge is how far it diverges from EU rules and mechanisms, since some form of ‘equivalence’ is likely to be the price of frictionless admission to EU markets. Regardless, in the current environment there is no plausible route to a ring-fenced, closed EU capital market. The EU should accept that global capital markets are here to stay and seek to maximise its involvement in those markets, and therefore its voice in their regulation.

In 2014, upon the establishment of the Juncker Commission, Jonathan Hill was made commissioner and given a portfolio called ‘Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union’. Jean-Claude Junker’s ‘mission letter’ to Hill tasked him with “bringing about a well-regulated and integrated capital markets union, encompassing all member-states, by 2019, with a view to maximising the benefits of capital markets and non-bank financial institutions for the real economy.”

The backdrop was the eurozone’s on-going economic travails and concerns about the over-reliance of European businesses on bank financing. European corporates were largely financed by banks in their home countries. This meant that the health of bank balance sheets, and therefore corporate balance sheets, were closely linked to the financial health of the country that hosted them. This link – whereby an economic contraction could lead to a bank failure, which could then lead to an economic contraction (known as the ‘death spiral’) – suppressed economic growth in those countries which most desperately needed it. Viewed from this perspective, it was clear that in order to break the cycle, and decouple the financial health of industry from the financial health of domestic governments, industry should be persuaded to fund itself through international capital markets, from non-bank investors. This would create pan-European shock absorbers, increasing the eurozone’s ability to weather future economic shocks.

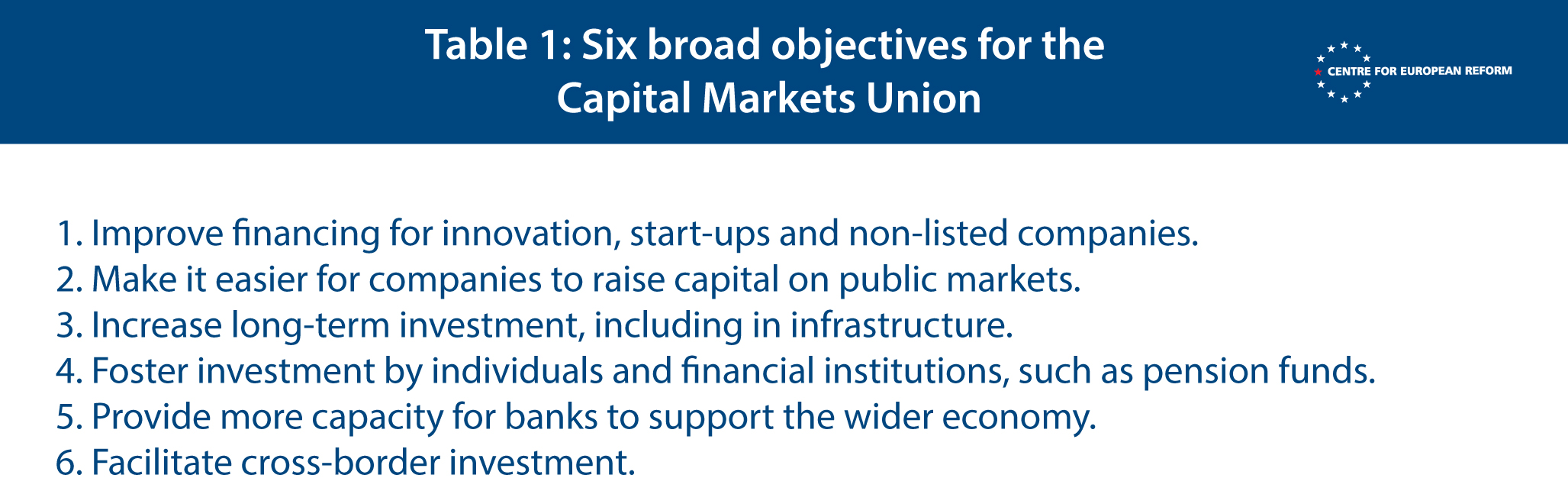

A lot has happened since 2014. Jonathan Hill is no longer a European Commissioner – the current commissioner in charge of creating the CMU is Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis. The Commission has tabled proposals and conducted consultations on various aspects of the CMU (see table 1). Most importantly, the member-state with the biggest European capital market, the UK, is set to leave the EU. Upon conception, it was argued that the CMU could not function without London’s involvement, and hence should not be a eurozone-only project. Paradoxically, with the UK leaving, some now argue that because London will be on the outside, the EU must push the CMU forward faster.

However, before deciding to race ahead, decision-makers should pause and consider the direction of travel. What should Europe’s capital markets look like post-Brexit? This policy brief lays out the options for the EU.

Why does Europe need capital markets?

European industry is excessively reliant on the banking sector for its finance, with smaller companies in particular proving reluctant to raise funds directly from the markets. This is in marked contrast with the funding of companies in the US. To simplify for illustrative purposes: the most successful small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Europe, the family firms of the German Mittelstand and northern Italy, continue to finance their activities through banks rather than the bond market. Reliance on banks for finance is sustainable so long as the banks themselves are reliable and stable, and so long as the borrowers are both established and highly creditworthy. However, the model of stable national banks financing stable national businesses curbs access to funding, and leaves companies overly exposed to localised economic downturns.

The practical difference between bank finance and capital market finance is simply that bank finance is intermediated. A bank can lend only as much as it can borrow, and it can borrow only to the extent that those who lend to it have confidence in it. Thus where there is a loss of confidence in a bank, the bank must call in its loans and withdraw from providing new financing in order to repay its creditors. Bank finance is therefore cyclical – it grows in a boom when confidence is high, and shrinks in a crash when confidence is low. Capital market finance, by contrast, is not intermediated. Bonds are generally bought directly by end-investors – pension funds, life insurance companies and the like. These investors generally do not respond to booms and busts in the same way as banks, because they are not reliant on short-term borrowing to fund long-term investments. As a result, firms funded by capital markets investors are less exposed to swings in market confidence than firms funded by bank credit.

The creation of an open, liquid trading market is essential for the development of capital market corporate finance.

However, one of the problems that CMU advocates must address is that a capital market is not exclusively composed of ‘buy-and-hold’ investors. Whereas bank credit is a private transaction, capital market credit is public: a company’s liabilities being bought and sold on a daily basis. The public nature of capital markets means they attract more scrutiny from the media, public and politicians than bank lending. It is not uncommon to hear such public lending markets described as a ‘casino’, in which investors are perceived to be placing high-risk bets without any means of controlling the outcome. However, such (sometimes adverse) attention is a necessary by-product of capital market finance. Generally speaking, bondholders will only buy bonds if they believe that they could sell them on if they need to, and they will only believe this if there is sufficient evidence that such a market does in fact exist.

To simplify: investors will only be attracted into a capital market if they believe that they will be able to get out again in reasonable time and at a fair price. In order to estimate the likelihood of that happening they will look at the depth and liquidity of the market – how much is traded on a daily basis, how many traders there are, and how substantial those traders are. A deep and liquid market means lower costs for borrowers; a thin and illiquid market means higher costs. Transparency is not an undesirable by-product of market financing, but the very thing which gives it its price and stability advantage over other forms of financing. In other words, liquid capital markets reduce the cost of capital to the economy as a whole.

This means that the creation of an open, liquid trading market is essential for the development of capital market corporate finance. As the European Commission said in its green paper on building a capital markets union:

“Improving the effectiveness of markets would enable the EU to achieve the benefits of greater market size and depth. These include more competition, greater choice and lower costs for investors as well as more efficient distribution of risks and better risk-sharing… Well-functioning capital markets will improve the allocation of capital in the economy, facilitating entrepreneurial risk-taking activities and investment in infrastructure and new technologies.”1

Finally, capital markets are the preferred mechanism for foreign direct investment (FDI) into an economy. By 2015, the EU-27 had received a stock of €5,692 billion of inward investment. And by that year, the major EU-27 exporters of capital measured in stocks of FDI to all worldwide destinations were Germany (€1,634 billion), France (€1,184 billion), the Netherlands (€948 billion), Spain (€426 billion), Italy (€421 billion) and Belgium (€414 billion).2 The same set of countries are the leading importers of capital, although on a somewhat smaller scale. The important question is, of course, how much of this FDI passes through the City. A European Parliament report estimates that approximately one half of all FDI flows between the UK and the EU consist of investment in financial services.3 FDI in financial services is mostly made up of the build-up of financial assets and liabilities in companies. The implication is that the proportion of global FDI which flows through the City into the rest of the EU is very large. Post-Brexit, assuming that it will be difficult to build mechanisms to replace the City immediately, the obstruction of flows of FDI into the EU-27 economy could pose a significant problem.

Despite being conceived before Brexit, the EU’s CMU must now be pursued in light of Brexit. The most sophisticated capital markets in Europe, and participants in them, are to be found in London. At the time of writing, the nature of the EU-UK relationship in respect of the financial sector is unresolved, but whatever the outcome the EU has tough decisions ahead of it as to the future of EU firms’ and investors’ access to capital.

The CMU so far

The CMU initiative is pushing at an open door. Since the financial crisis, corporations – including large EU corporations – have increased their reliance on bond market finance. This is largely driven by the reduction in bank lending capacity caused by increases in bank capital requirements. Bonds made up 19 per cent of total global corporate debt in 2018, nearly double the share in 2007.4 From the perspective of European corporates, the question is not whether they should raise capital through financial markets; it is a question of which markets they should use to raise that capital.

The EU’s progress towards a single EU capital market has been erratic. A fully-fledged CMU requires the harmonisation of many policies. Those include major areas of national policy-making such as insolvency, corporate and tax laws, in which resistance from national governments to harmonisation is formidable. It is therefore not surprising that there has been little progress on these important building blocks of a unified capital market. Instead, the Commission has focused on product market rules and supervision, to remove some smaller obstacles. These include regulation on common European rules on securitisation, covered bonds or sustainable investments; making it easier for retail investors to invest across borders, for example into a pan-European personal pension product; and simplifying or reviewing existing regulation on such issues as investment prospectuses. The Commission said it had “delivered on all its commitments”, and “tabled all legislative proposals set out in the capital markets union action plan and mid-term review to put in place the key building blocks of the CMU” in March 2019.5 While this may be true, there is still a lengthy to-do list before even this limited agenda is completed, let alone harmonisation of taxation, corporate and insolvency laws.

How can the EU create an effective capital market?

Market liquidity is essential to the creation of an efficient and effective capital market. As noted earlier, the propensity of an investor to buy a company’s debt depends upon the ease with which they can sell it. Where there is a deep and liquid market for a bond, the bond buyer will pay a lower price (that is, the issuer will get cheaper credit) than would be the case if the buyer feared that they would be locked into the investment for years to come. Capital markets enable credit providers to price the credit they provide as short-term (because the bond they own can be sold tomorrow), whilst issuers get long-term funding (since they are indifferent to the fact that the bond has been bought and sold). The deeper and more liquid the market, the more effectively this process works.

Long-term investments can be sold short-term on a market, but that requires deep and liquid markets to work effectively.

Liquidity, in turn, is provided by dealers. In particular, dealers who are prepared both to buy and sell securities in their own name, and to promise to buy and sell securities to market participants in order to keep markets liquid (often referred to as ‘market makers’). These dealers are sometimes traditional banks, sometimes investment banks, and sometimes specialist trading businesses. However, in this regard, their approach is the same: they take risk by buying securities, holding onto them for a period, and then selling them in an attempt to make a small profit on each transaction.6 In general, the larger the positions that these dealers are prepared to take, and the longer they are prepared to hold them for, the more liquid the market will be – they are, in effect, the buyers and sellers of last resort, and their presence emboldens other market participants. However, since all securities dealers are (by definition) regulated investment firms, they cannot take risk or hold positions unless they have enough regulatory capital to do so. Thus, a good proxy for the liquidity of a market is the amount of capital which dealers in that market have available to support their trading inventories, and the size of the inventory which that capital can support.7

The liquidity of a market is therefore proportional to the size of the trading inventories of the market makers. There are only two ways to increase the size of these inventories: either market makers can choose to commit more capital, or borrow more. Encouraging securities dealers to borrow more to finance their market-making activity is ill-advised – it would most certainly threaten systemic stability. As such, the development of an EU capital market requires either an increased appetite amongst investors for financial market risk, or existing financial market participants to divert their existing capital from other activities and into financial markets trading.

There is little chance of either of these options happening. Investors are currently capital-constrained, risk-averse, under significant political pressure to invest in the so-called real economy, and facing massively increased regulatory capital requirements on their financial market activities. A study of the current state of capital markets by the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) revealed that (pre-tax) return on equity (ROE) from 2010 to 2016 dropped from 17 per cent to just 3 per cent as a result, taking into account risk mitigation measures. It should also be noted that these mitigation measures included a 40 per cent reduction in the balance sheet capacity committed to capital markets.8 With another significant increase in capital requirements (the implementation of the Basel Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB)) due to take effect in Europe by 2022, it is almost certain that returns on capital from trading will fall further, and the amount of capital committed to trading will also fall.

European banks and firms are reducing the amount of capital committed to supporting market liquidity.

Put plainly: the liquidity of global capital markets is decreasing in absolute terms. European banks and firms are reducing the amount of capital committed to supporting market liquidity, and their ability to leverage that capital is, at the same time, being reduced.

Market illiquidity has a cost to the real economy, but estimating that cost is difficult. However, recent experience provides some data. After the financial crisis, bank regulators significantly increased the capital requirements for banks engaging in market-making activity. This increase resulted in a corresponding decline in bank trading positions, and therefore in market liquidity, globally. Policy-makers argued that this reduction was a net benefit to the financial system, since the reduced prospects of a crisis resulting from increased capital more than offset the resulting loss of market efficiency.9

However, the interesting question for us is the gross cost of that reduction. Ignoring all other factors, what is the cost of a reduction in market liquidity to the economy? Bank of England researchers estimated that the resulting increase in costs of trading in the bond markets resulted in GDP being 0.2 per cent smaller than it would otherwise have been.10 Thus the basic point – that shrinking capital market liquidity directly impacts GDP growth – seems clearly established.

A further point that the Bank of England researchers made was that bond and loan markets are closely connected, since bond markets, being public, are generally used as reference points for the pricing of loan finance. Thus a widening of spreads in the bond markets will tend to drive up bank loan rates. This means that an inefficient bond market will tend to have a detrimental effect on costs of business finance even in regions (such as continental Europe) where business is predominantly loan-financed rather than bond-financed.

More importantly, those EU firms which are global market participants face a choice as to where to allocate their increasingly scarce capital. It is unlikely that such firms would chose to allocate capital to an anaemic continental European market, unless the spreads in that market were sufficiently wide to compensate them for the liquidity risk inherent in taking positions in an illiquid market. And, as noted above, very wide spreads in capital markets have a detrimental effect on economic growth. This means that the less open the EU market is, the less liquid it will be, and the less likely it is that non-EU firms will wish to (or be able to) commit capital to that market.

Not all securities markets are equally dependent on intermediaries (banks or other institutions that funnel finance between end investors and enterprises). The Bank of England draws a distinction between markets that are less reliant on intermediaries putting capital at risk to facilitate transactions between investors (such as equity markets), and markets that are more reliant on intermediaries putting capital at risk (such as corporate bond markets).11

In general, the more liquid the market, the less important intermediary capital is. For example, an investor in highly sought after short-term US treasury paper will be confident that they will be able to find buyers for that instrument regardless of the capacity of the market. Therefore, in the bonds of larger governments, the most liquid equity markets, and the bonds of a few very large corporates the need for intermediation is reduced and there has been a move towards fast, electronic trading. This does not, however, apply to the equities of smaller firms, nor even for the equities of big companies, where liquidity in times of market turbulence may be at risk in the absence of intermediaries. In corporate bond markets, which are generally highly illiquid, the effect is even greater.

The upshot: if European firms are deprived of access to the intermediaries in the London market, which is by far the largest and most open capital market in Europe, the question of where and to whom they can sell these instruments will become important.

The EU and the world

If the supply of capital within Europe is unable to meet the demands of European businesses, the EU should make sure that its markets are as open as possible to capital providers from elsewhere in the world. Such an approach would, however, give EU legislators and regulators – who worry that increased non-EU participation in EU capital markets will undermine regulatory standards – cause for concern. These concerns, and the measures put in place to address them, will determine how open Europe’s capital markets will be post-Brexit.

Any ‘raising of the drawbridge’ against the UK would mean raising the drawbridge to international finance in general.

While London was embedded within the EU, the focus of EU policy-makers was on improving EU market regulation, with measures to prevent market abuse and improve business conduct, for example. However, some argue that the effect of these measures was a soft closing of the EU’s markets, with firms required to obtain EU authorisation and subject themselves to EU rules in order to be permitted to participate in European markets.

Brexit has significant implications for the impact of those measures. The ‘soft closing’ which was designed to protect EU markets now runs the risk of isolating them from the largest financial centre in Europe. The EU has taken the view that the UK is not a special case, and that, post-Brexit, EU law should be enforced in the same manner as it was before.

This problem is enhanced by the (understandable) tendency in Brussels to look holistically at EU-UK arrangements and attempt to eke out negotiating levers in every aspect of regulation. In particular, it believes that, since access to EU customers is a priority for UK firms, the denial of such access is a potential negotiating tool for the EU. The Commission’s recent attempt to use the threat of derecognition of the Swiss stock market as a bargaining tool in the EU-Swiss treaty negotiation is an example of this happening on a smaller scale.

However, the EU’s own equivalence rules would make it extremely difficult for Europe to apply actively discriminatory measures to the UK without applying equivalent measures to American, Asian and other foreign firms. Since the EU is, above all, a rules-based system, it struggles not to act in accordance with its own rules. As such, any ‘raising of the drawbridge’ against the UK would mean raising the drawbridge to international finance in general.

In the immediate aftermath of the Brexit referendum, many in Europe hoped that the problem would resolve itself by financial firms relocating from London to the EU. It now seems unlikely that this will happen, at least in the short-term. Firms are establishing subsidiaries in the EU and will book transactions with EU counterparts with those subsidiaries, but their guiding minds will remain in London. This configuration may change over time but is unlikely to do so immediately. Consequently, there is scope to examine the fundamental issue which will face EU financial services policy-makers post-Brexit: how open should EU capital markets be to non-EU participants?

The case for closed markets

The argument for a closed approach is borne of a desire to protect Europe from exogenous shocks. After Brexit, unless the British have a change of heart and pursue a much closer relationship than currently envisioned, the EU will be in the uncomfortable position of having no regulatory control over the financial market its economy relies on for access to global capital markets. This situation is by no means unique – Canada, Mexico, Russia and many other major economies are all in the same position – but it will significantly alter the EU’s perception of its own role in the financial world. This loss of control is also viewed – correctly – in Brussels as a significant reduction in the ability of EU regulators to protect EU citizens. It would be difficult for European policy-makers to simply accept this outcome as a fait accompli – there is too much at stake.

Viewed from this perspective, a closed EU capital market has its attractions. The fewer the direct links between EU and UK financial firms, the lower the risk of contagion were a crisis to hit London. And if EU banks could be persuaded to deal only with other EU banks on EU trading platforms, then the EU could regard itself as having restored its sovereignty in this area.

The case for open markets

A closed market approach has drawbacks, however. For one, an insulated EU capital market would be too small to finance the EU economy efficiently. EU companies, savings institutions and other market users would be forced to relocate a significant proportion of their activities outside of the EU to enable continued access to global markets. Flows of inward financial investment into EU economies, which currently enter via the London market, run the risk of being diverted away from the EU.

To complicate matters further, capital markets in the EU are currently supervised by national, member-state, authorities, and there is no collective desire to move to an EU-wide model. There is a logic to this approach – different member-states have different fund-raising and investment needs and, indeed, ideologies and outlooks on financial markets. The core issues mirror those in the macro-economic sphere. How much risk sharing is necessary and how much risk reduction does there need to be as a pre-requisite? There is no scientific answer to this question; it is inherently political.

The departure of the UK will affect non-euro member-states the most in respect of their relationship with the EU’s banking and capital markets unions. The British played a key role in the design of the mechanism by which non-euro member-states could join the banking union, if they so choose. While the CMU is not a euro-related project, the sensitivities of countries such as the Czech Republic, Denmark, Poland and Sweden have to be accounted for, even in the absence of a loud voice fighting their corner. More importantly, it is a gross oversimplification to reduce EU protagonists to France, Germany and the departing UK. Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Ireland are examples of countries with important interests in the development of European capital markets.

Conversely, if the EU were to embrace the underlying logic of the CMU proposals, it would facilitate the access of large global financial institutions to the EU market. That would create a significant EU market, substantially expand the proportion of global financial activity under the EU’s direct regulatory control, and amplify the EU’s voice in global financial forums. However, this approach would significantly enhance the links between the EU and global markets, and therefore expose the EU to financial crises that arose elsewhere. Also, such an approach would result in significant pressure being exerted on the EU to accommodate its regulatory approach to global standards, and thereby to reduce its scope for idiosyncratic policy measures.

European markets – open or closed?

It appears that there are good arguments for both open and closed European financial markets. However, this is a false dichotomy. It is true that maintaining an open approach to financial markets would expose the EU to global market fluctuations. But it is not true that maintaining a closed approach would protect it from those fluctuations. When the US’s secondary mortgage securitisation market went into meltdown in 2007-8, the result was not a regional collapse in the US, but a more general collapse in credit markets worldwide; a tremor which shakes Citibank can be felt on the banks of the Rhine, and a tremor which shakes Deutsche Bank can be felt on the Hudson. It is 50 years too late to restore economic autarky in any part of the global financial market, and attempts to do so are unlikely to result in stronger or more stable markets. Indeed, a closed market strategy which produced a thin and anaemic market would probably leave that market more, rather than less, vulnerable to external shocks.

The answer must be a compromise that gives Europe some involvement in the regulation of the London markets.

Closed markets are not the answer. However, fully open markets threaten the EU with a complete loss of regulatory control. The answer must therefore be a compromise that gives Europe some involvement in the formulation and implementation of regulation in the London markets. The British authorities should not be resistant to the EU having that involvement, any more than they are resistant to the EU having a voice in global financial regulation: the EU has legitimate interests and is one of the largest customers of the London market. Conversely, if the EU is satisfied it has sufficient say in the regulation of London, there ceases to be any good reason to place obstacles in the way of London firms servicing EU clients.

The obvious mechanism for a co-operation agreement of this kind would be a joint policy-making forum between the UK and the EU regulatory authorities, with formal structures in place governing supervision and enforcement of institutions active in both markets. While informal arrangements do exist – such as those the UK have with the US – they only work because they have been developed over many years and are well understood by market participants. If such an arrangement is to be created between the EU and UK from scratch, over a short period, it would be preferable if it were accompanied by some degree of formality – if only to reassure market participants.

The EU may resist such entanglement by relying on equivalence. Equivalence has the enormous advantage of autonomy – the EU can declare a counterparty to be equivalent or not as it sees fit. This creates the possibility of equivalence being used as a tool to obtain indirect regulatory involvement in third countries – the idea being that a third country can be persuaded to adopt EU rules under the threat of lost equivalence. However, equivalence is a big stick but a small carrot. It can be used as regulatory leverage in those circumstances where equivalence is currently in place, is relied upon significantly by market participants, and where the threat of derecognition would have a significant negative effect on the third country concerned. (Although the attempt to use this weapon against Switzerland in 2018 over equity trading is widely regarded as having been a failure). However, once equivalence has been refused, market participants will make other arrangements to execute the business in question. And once such arrangements have been made, it is unlikely that obtaining equivalence will be a significant policy objective for the relevant government in the future. The more easily banks and others can deal with EU clients without equivalence, the less valuable the offer of equivalence becomes as a bargaining chip.

A policy conundrum

The EU has already demonstrated that a deep, liquid and globally connected capital market is important for the European economy. More importantly, the days of financial autarky are gone, and Europe cannot bring them back. Europe must accept that its future is as a participant in the regulation of global financial markets, and seek to maximise its involvement in those markets, and its voice in their regulation.

There are a number of aspects to this. One is full participation in the global standard-setting bodies for bank, securities and accounting regulation – in Basel, the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and other venues – with the concomitant obligation to implement those standards domestically. Another is involvement in the existing transatlantic dialogue with US regulators and standard-setters. The most important aspect, however, is the relationship with the UK, and in particular the regulators and supervisors of the London markets. Regardless of the legal form of the arrangement, the EU needs to ensure regular exchange of information, deep supervisory co-operation and joint policy-making on new issues between EU and UK authorities. This could have been best managed through a mutual recognition arrangement – but such an arrangement was always a London pipe-dream; the EU will not accept mutual recognition in financial services, and there was never any chance of it being extended to an exiting country. In the absence of legally binding measures, formal, institutionalised co-operation should remain the ultimate objective of supervisors and regulators on both sides of the channel regardless of the legal form of the eventual settlement between the UK and the EU.

2. European Parliament, ‘Economic and scientific policy: An assessment of the impact of Brexit on the EU-27’, Study for the IMCO Committee, 2017, Annex 6.

3. European Parliament, ‘Economic and scientific policy: An assessment of the impact of Brexit on the EU-27’, Study for the IMCO Committee, 2017.

4. Susan Lund and others, ‘Rising corporate debt: Peril of promise?’, McKinsey Global Institute, June 2018.

5. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, ‘Capital markets union: Progress on building a single market for capital for a strong Economic and Monetary Union’, March 2019.

6. The profit on securities dealing can only ever be small, because if it became too large investors will cease to use the market. Even a monopoly securities dealer does not seek to increase the profit on individual securities transactions beyond accepted levels – rather they seek to increase the number of those transactions.

7. For an exhaustive analysis of market liquidity, see PWC, ‘Global financial markets liquidity study’, August 2015.

8. AFME and PWC, ‘Impact of regulation on banks’ capital markets activities: An ex-post assessment’, April 2018.

9. See Hyun Song Shin, ‘Market liquidity and bank capital’, speech, Bank of International Settlements Quarterly Review, April 27th 2016.

10. Yuliya Baranova, Zijun Liu and Tamarah Shakir, ‘Dealer intermediation, market liquidity and the impact of regulatory reform’, Bank of England, July 2017.

11. Niki Anderson, Lewis Webber, Joseph Noss, Daniel Beale and Liam Crowley-Reidy, ‘The resilience of financial market liquidity’, Bank of England, October 2015.

Sir Jonathan Faull

Chair, European Public Affairs, Brunswick Group. European Commission 1978-2016. Member of the CER Advisory Board. All views expressed are personal.

Simon Gleeson

Partner, Clifford Chance

View press release

Download full publication here