Putin's last term: Taking the long view

- Vladimir Putin has dominated the Russian political scene since 1999. But he is now in what should be his final term as president. He faces economic, social and foreign policy problems; and he has to decide what will happen at the end of his term of office.

- The performance of the Russian economy in recent years has been mixed. Inflation has fallen, foreign reserves have risen and the ruble’s exchange rate is relatively stable; but growth has been anaemic and real disposable incomes have fallen.

- Putin has set ambitious economic targets for his final term, but is unlikely to achieve them. Russia is not investing enough in education to enable it to modernise and diversify the economy. The oil and gas sector is too dominant. Structural reforms (such as moving investment from the defence sector to other, more productive areas) are not on the cards.

- Russia has suffered from demographic problems since the Soviet period. With a shrinking working-age population and an increasing number of unhealthy pensioners, Russia risks stagnation, while countries like China leap ahead.

- Putin has yet to give any hint of his thinking about his successor. He could find a trusted individual to take over as president; change the Russian Constitution to allow himself to run again; or create a new position from which he could still exercise power. But if he stays in power too long, Russia could become like the late Soviet Union – a system unable to renew itself.

- In foreign policy, Putin has had a number of successes, and when the West has pushed back, for example by imposing sanctions after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, his regime has used the external pressure as a unifying force at home. He has regained some of the influence in international affairs that Moscow lost when the Soviet Union broke up. He has engaged with other great powers in solving shared problems, when it has suited him; he has acted decisively when the West has hesitated; and he has been adept in exploiting the West’s internal divisions.

- In dealing with Putin, Western policy-makers need to act as though nothing will ever change in Russia, and as though everything might change overnight. That means ensuring that the West itself is resilient in the face of threats; but also that the door is open to improvements in relations. Russia needs to consider whether its interests would be better served by having more co-operative relations with its neighbours – a policy that would also build trust with the West.

- Russia and the West should talk about some of the issues that divide them, even if agreement on what to do about them will have to await fundamental political changes. International security, including nuclear and conventional arms control, should be at the top of the agenda. New areas of confrontation, such as outer space and cyber space, should also feature. The two sides should look for shared problems, such as climate change or global health, that they could tackle together or at least in parallel.

- For Putin, a better relationship with the West could be part of his legacy. And the West has an interest in laying the foundations for a stable relationship for the rest of the Putin era and beyond.

It is 20 years since Russia, in the midst of its post-Soviet economic crisis, with workers unpaid and an ever-growing gap between state revenue and expenditure, defaulted on its debts and devalued its currency. In the midst of the chaos, President Boris Yeltsin appointed an obscure former deputy mayor of St Petersburg, Vladimir Putin, as head of the Federal Security Service (the inheritor of most of the Soviet era KGB’s internal security functions). A year later, in August 1999, Putin became prime minister and Yeltsin’s anointed heir.

Putin has dominated the Russian political scene ever since. In his first dozen years in power, Putin benefited from high oil-prices. The resulting high growth rates gave the Russian population a new sense of confidence after the turmoil of the economic crisis. When oil prices turned against him and the economy weakened, Putin changed his narrative, making more overt use of nationalist themes and hostility to the West. This period culminated in the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014.

Though Russia has been under Western sanctions since then, Putin has been able to exploit divisions in Western societies and failures in Western policy-making to strengthen his position on the international stage. Whether Russian influence played a decisive role in the UK’s Brexit referendum, the election of Donald Trump as US president or the strengthening of populists in Italy and elsewhere in Europe hardly matters: Putin certainly favoured all those outcomes and has benefited from the political disruption they have caused in the EU and NATO.

After an election in March 2018 from which Putin’s most effective critic, the anti-corruption campaigner Aleksey Navalniy, was excluded on dubious legal grounds, Putin was inaugurated on May 7th for what (according to the Russian constitution) should be his final six-year term as president. He faces long-term, structural economic challenges; serious social problems; and a variety of difficult foreign and security policy problems. For the first time since before he annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 he is seeing his opinion poll ratings fall, and public opposition to his domestic policies grow. And above all, he has to decide on what happens in 2024: who will succeed him, and what will his own role be when he leaves office?

This policy brief, written jointly by a Russian and a British author, aims to take account of both Western and Russian perspectives on the way ahead. It analyses the Russian economy and the proposals that Putin and his advisers have put forward for reforming it; and looks at Russia’s foreign trade and patterns of economic relationships. It analyses Russia’s demography, and the impact that migration within and from outside Russia will have. It considers the weakness of Russia’s institutions and the implications that has for Putin’s decisions on who should succeed him and for the long-term strength of the state. It examines Russia’s relations with other international actors, in particular China, the EU and the US; and Russia’s involvement in conflicts, both in former Soviet states and further afield in the Middle East. And finally it considers whether Russia and the West can or should try to do anything more ambitious in the remainder of the Putin era than avoiding conflict.

The economic context for Putin’s term of office

Putin’s problem with the current state of the economy is not that it is very bad (the picture is more mixed than that), but that it is nothing like as good as he said it would be when he was inaugurated in 2012. Before looking at his targets for 2018-2024, it is worth examining where he fell short in 2012-2018. In 2012 he began his term by issuing 11 decrees setting out detailed targets for the government. But he left the government very little flexibility, and when external circumstances changed, many of the targets were missed. Of those that were achieved or at least claimed, some successes could be attributed to the performance of the Russian government, but others were either a result of external developments, or the manipulation of statistics.

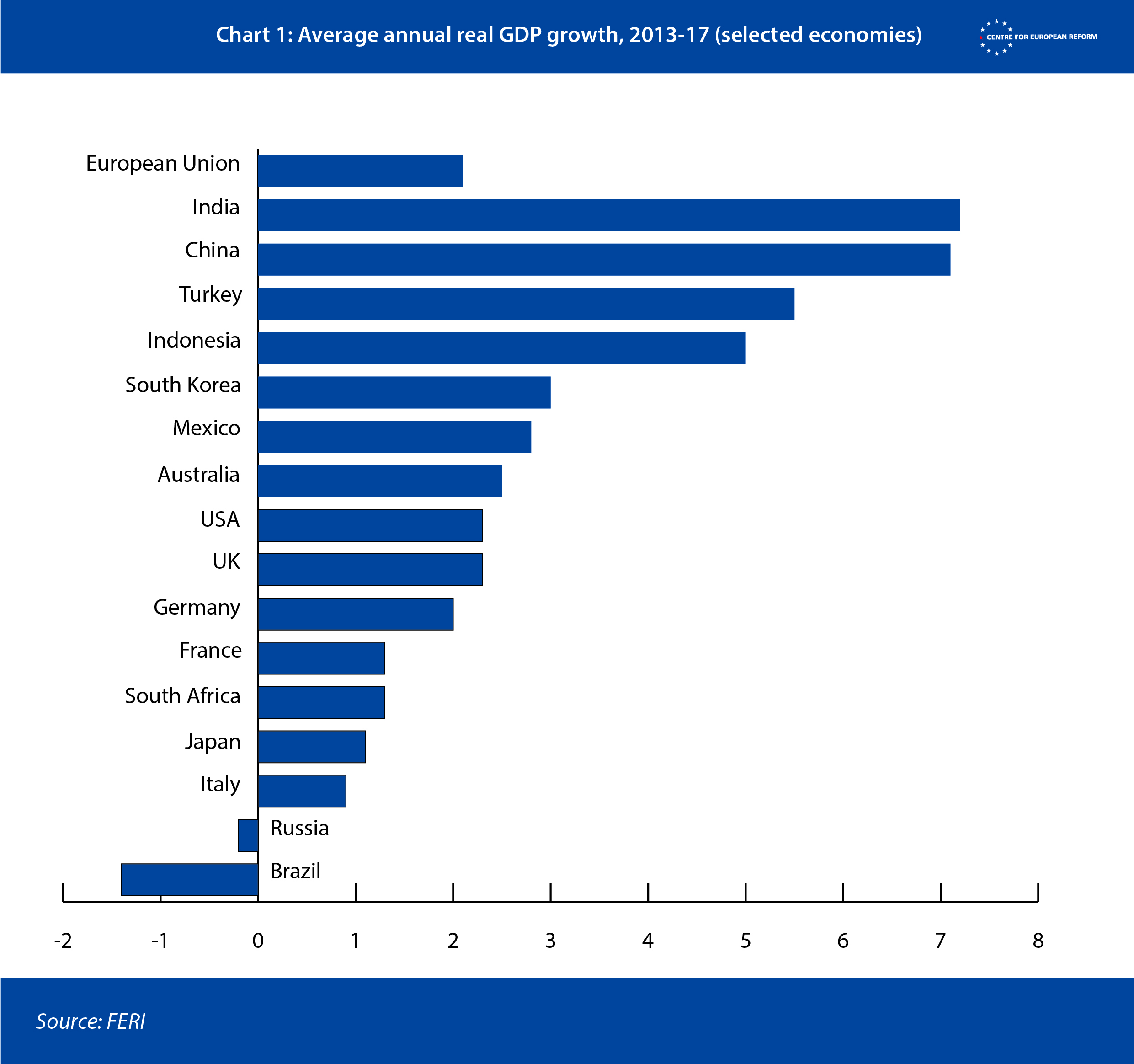

Overall, the targets set in 2012 proved to be too ambitious, especially after the 2014 conflict in Ukraine led to open confrontation with the West and a succession of sanctions and counter-sanctions. Coupled with a long-standing preference for guns over butter, these conditions led to Russia’s economy shrinking on average by 0.2 per cent per year between 2013 and 2017 (Chart 1).

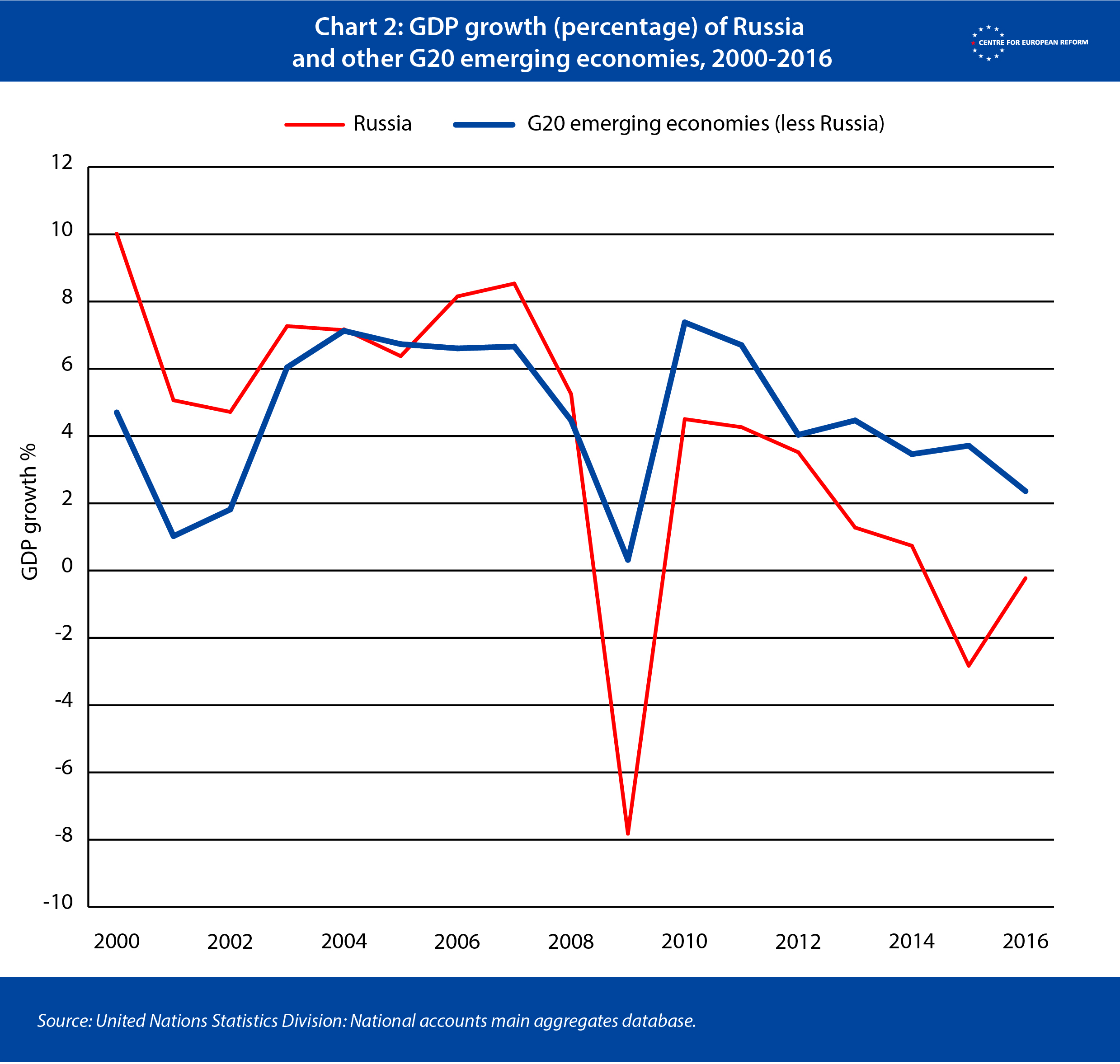

Among major economies, only Brazil performed worse than Russia, averaging -1.4 per cent. Meanwhile, the EU’s economy grew by 2.1 per cent a year and the US’s by 2.3 per cent. In eight of the first nine years after Putin came to power, Russia’s growth rate was higher than the average of the other nine emerging economies among the G20. In 2008 Russia grew by 5.2 per cent versus 4.5 per cent for the other nine; but the economic crisis that began that year hit Russia harder than any of the others. Its growth rate has remained below the average of the other nine in every subsequent year (Chart 2).1

The economic situation at the start of his latest term is not all bad news for Putin. The price of crude oil averaged around $70 per barrel in 2018, well above the level the government assumed when estimating its revenues for the year (though the price in December fell to around $55). Russian government debt is relatively low at an estimated 15 per cent of GDP. Central Bank of Russia data shows that Russia’s international reserves at the end of October 2018 were over $450 billion, having risen by more than $30 billion in the previous year. Russia had enough foreign exchange reserves to cover 18 months of imports (by comparison, UK foreign exchange reserves would cover only two and a half months of imports).2Russia’s sovereign wealth fund, the National Welfare Fund, amounts to $76 billion, or 5 per cent of GDP.

The Central Bank of Russia has managed to stabilise both inflation and the ruble’s exchange rate. Consumer price inflation in December 2018 was 4.2 per cent year-on-year, after shooting up to 15.5 per cent in 2015 under the pressure of Western sanctions, Russian counter-sanctions and a sharp fall in the value of the ruble (caused by a drop in oil prices). The ruble’s real effective exchange rate – which measures the value of a currency against a basket of currencies, corrected for differences in inflation – is rising again, after falling by 25 per cent between 2013 and 2016, and now stands at 93 per cent of its 2010 value.3

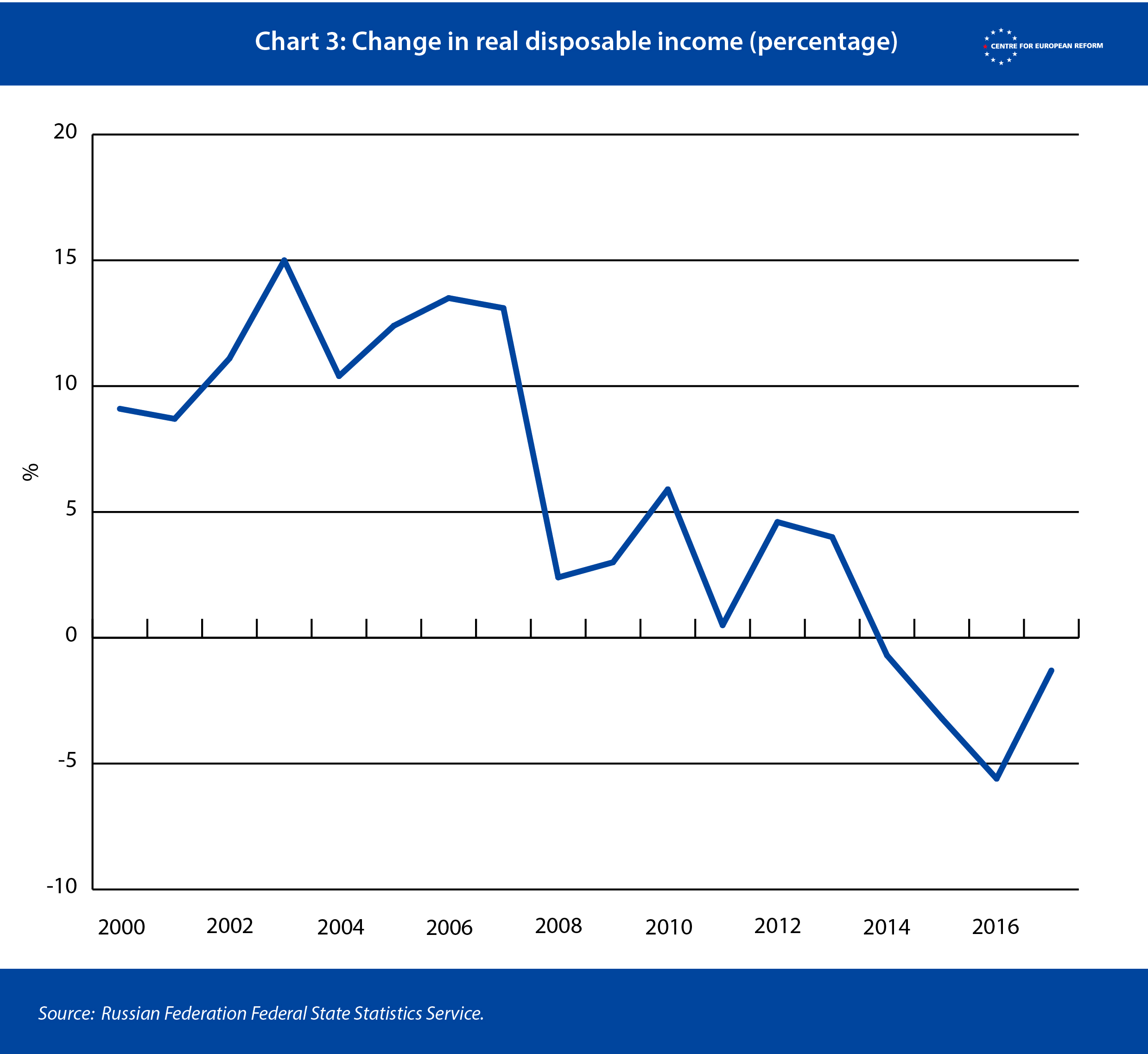

At the same time, after growing throughout Putin’s first 12 years in power, real wages fell by around 10 per cent between 2014 and 2017. While this cut has helped to preserve jobs, real disposable incomes, after growing strongly before the crisis, have fallen in every year since 2013 (Chart 3).

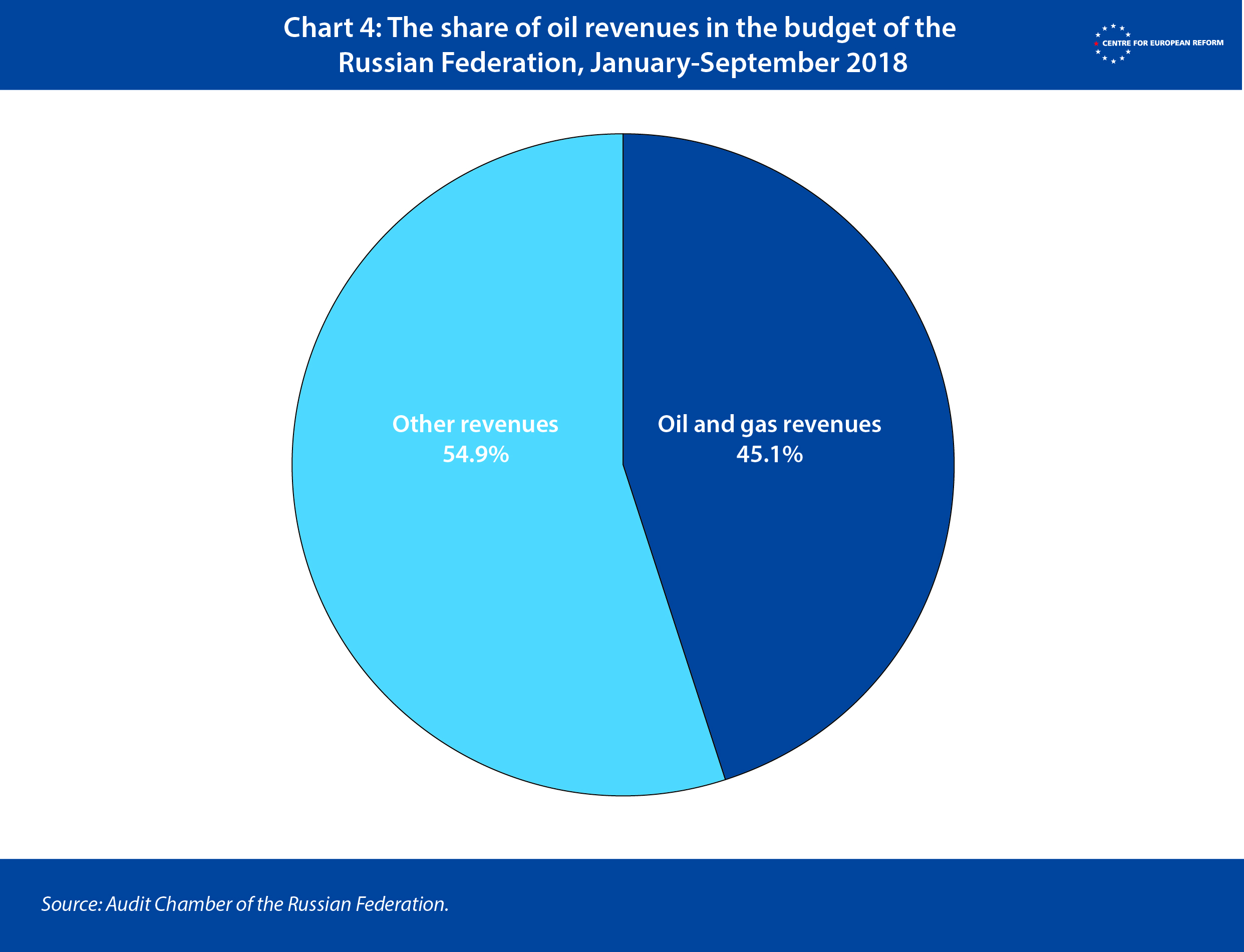

The oil and gas sector plays a predominant role in Russia both economically and politically. In 2017 Russia produced about 11 million barrels of crude oil per day – more than Saudi Arabia. Oil and gas production fuels economic growth and provides funds which the government can spend to ensure domestic stability. According to the Russian Audit Chamber, oil and gas revenues together made up 45.1 per cent of total federal budget revenues in the first nine months of 2018, more than five per cent higher than a year earlier (Chart 4).

Putin’s programme

Immediately after his inauguration on May 7th 2018 Putin set out ‘national goals’ and ‘strategic targets’ for the government of Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev, in a wide range of economic and social fields, in a single ‘May decree’ (as opposed to the 11 separate decrees of 2012). The aims include making Russia one of the world’s five largest economies, ensuring sustainable natural population growth, cutting poverty in half, and speeding up the introduction of digital technologies in the economy and society.

The 2024 agenda set out in the May decree could in some respects have shown better integration between the various goals and targets, and been more specific, but, on the whole, it was well-designed. It set out nine ‘national goals’, and instructed the government to present by October 1st 12 ‘national programmes’ for achieving them. It looked forward to Russia making the maximum possible progress at the cost of the lowest possible turmoil – an approach that fully meets the expectations of the majority of the Russian electorate.

By the next presidential elections, the May decree pledges a growth in welfare (cutting the poverty level in half, yearly improvement of the housing conditions for at least 5 million families, and so on), along with an improvement in the demographic statistics (sustainable natural growth of the population, life expectancy increased from the current 72 years to 78 years) and acceleration of technological development (including increasing the use of digital technologies in business and the social sphere).

The list of targets also includes a minimum of five per cent growth per year in labour productivity at medium and large enterprises in national industries outside the resource sector; a threefold increase in domestic expenditure on building the digital economy; ensuring that Russia is among the top five countries for research and development in the priority fields of scientific and technological development (though what these priority fields are is not specified); inclusion in the top ten countries with the highest standards of general education; and drastic modernisation and expansion of basic infrastructure. Consistent with these aims, Russia is also planning to become one of the five largest economies in the world (by purchasing power parity, which now places it sixth, after Germany).

Will Putin hit his targets?

There are reasons to doubt that most of the economic targets in the May decree will be reached. Speaking at the Saint Petersburg Economic Forum in late May 2018, Christine Lagarde, International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director, said “Russia has put in place an admirable macroeconomic framework”. However, in October the IMF estimated that Russia’s GDP would grow by 1.7 percent in 2018 and 1.8 percent in 2019, which is about half the global average. Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development is more optimistic, forecasting growth of 2.1 per cent in 2018, 2.2 per cent in 2019 and 2.3 per cent in 2020 (Table 1). But this is still relatively sluggish growth for an emerging economy. The reasons for this, as Lagarde went on to explain, remain the same – the poor demographic situation, the low productivity of labour, and underinvestment in education and skills.

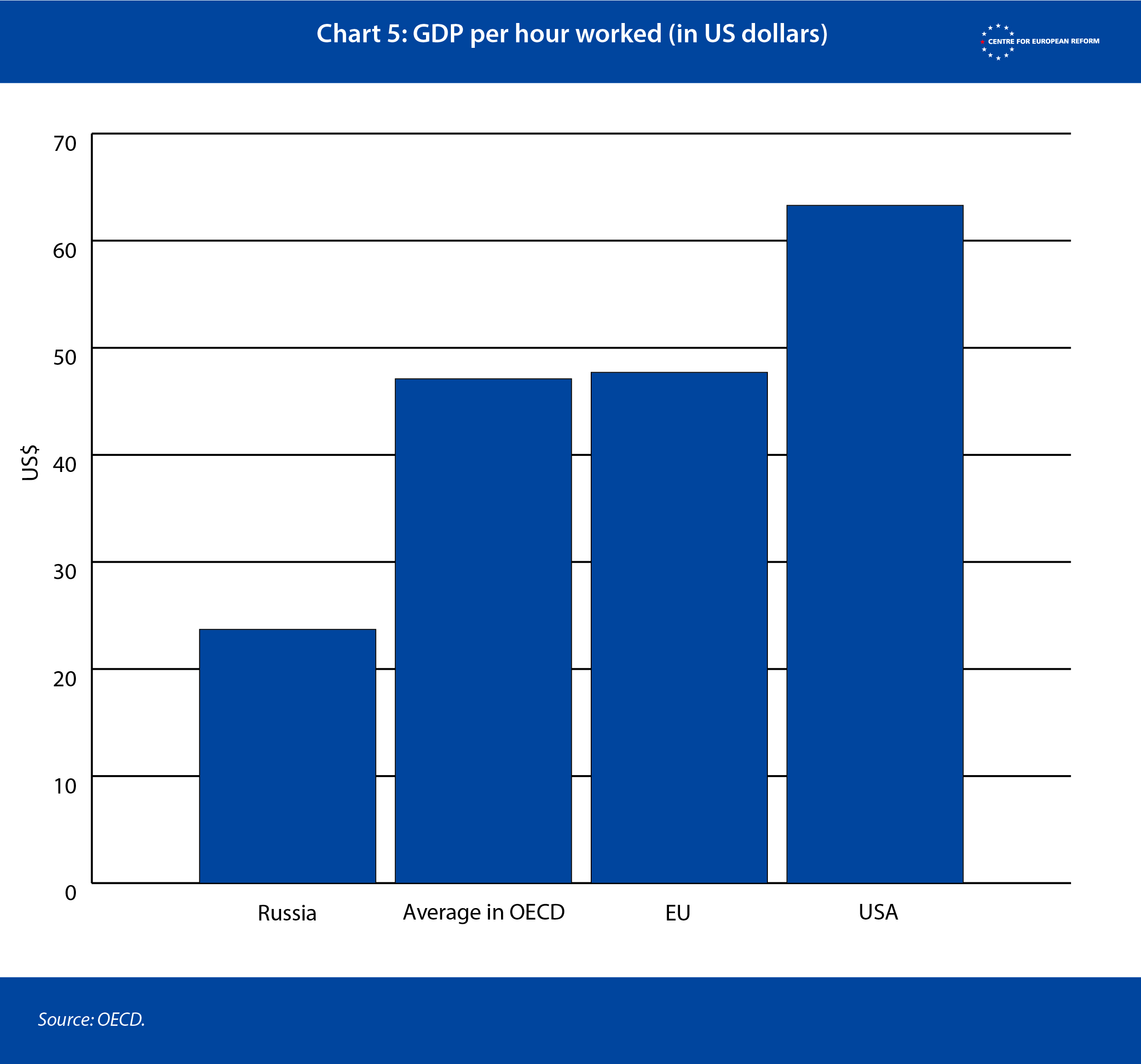

Reaching Putin’s targets requires deep economic and institutional reforms, and a lot of investment. Russia must keep inflation low and the currency stable; these are realistic aims, since monetary policy has been and remains the strong point of the current authorities. But more far-reaching progress will also depend on Russia achieving growth rates exceeding those of recent years, and of comparable countries. As Lagarde highlighted, Russia’s productivity in terms of GDP per hour worked is less than half of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average, and less than 40 per cent of the US level (Chart 5).

The hydrocarbon sector, which plays such a large part in the economy, is unlikely to be a source of broad-based productivity growth. Indeed, it would be a mistake for the government to be complacent about the future of the sector. First, US unconventional oil and gas production (oil and gas from shale formations rather than conventional deposits) has had and will continue to have a significant impact on the market. Production of US ‘tight’ oil (oil trapped in shale or sandstone, extracted by hydraulic fracturing) has risen from less than 0.4 million barrels per day in 2000 to more than 6 million in 2018, enabling US total crude oil production in August 2018 to exceed 11 million barrels per day for the first time ever.4 Meanwhile, US shale gas production has risen from less than 60 million cubic metres per day to almost 1.6 billion cubic meters per day over the same period – around the same as Russia’s total gas production.5

Second, Russia may be approaching peak oil production: the energy minister, Aleksandr Novak, warned in September 2018 that production might reach its maximum in 2021, before falling by almost half in the next 15 years.6 His claim should be treated cautiously, since it was made in the context of the oil industry lobbying against tax increases that Novak said would force production cuts. But over time, if Russia is to maintain current production it will need to exploit new oil and gas fields in more difficult areas, including the Arctic. US and European sanctions have prevented Russia from getting access to the Western technology needed in these areas.

More positively for the Russian oil and gas sector, the growth of renewable sources of energy in the world does not yet threaten its prospects. The Russian leadership can take comfort from estimates of steady growth in the demand for oil until at least the 2030’s. Russia’s position in global oil production is such that the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cannot manipulate the oil price without Russian participation – an important element in Russia’s political as well as economic calculus.

The state-owned gas company Gazprom, in spite of all its political difficulties over the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, maintains its position as Europe’s leading gas supplier, giving it considerable political influence in some European countries. By any corporate standards Gazprom is not run efficiently. A leaked analytical report in May 2018 from the state-owned savings bank Sberbank demonstrated that Gazprom pipeline projects favour the business interests of those who are close to Kremlin, rather than Gazprom shareholders.7 The authorities have allowed some competition in the previously monopolised sector by promoting the production and export of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Privately-owned Novatek and the state-controlled oil giant Rosneft are both lobbying for liberalisation of gas exports. The question is whether by 2024 Putin will have laid the foundations either for an economy less dependent on hydrocarbons, or for the Russian oil and gas sector to become more innovative.

Though its development in recent years is a comparative success, growth in agricultural production and exports will also be unable to drive modernisation of the Russian economy.8 The conditions under which agricultural production has increased have been artificial: Russia encouraged import substitution when it imposed sanctions on Western food imports in 2014, in retaliation for EU and other Western sanctions against Russia for its annexation of Crimea and intervention in Eastern Ukraine. As a result, investment in Russia was diverted from more competitive sectors of the economy into producing more expensive local substitutes for banned foreign food products.

If it is at all serious about modernising and diversifying the economy, Russia needs to invest more in education.

Structurally, small and medium enterprises make up a relatively small proportion of the agricultural sector’s output, while ten large holding companies dominate production and distribution. Unlike the US, Russia has a lot of very small-scale individual producers (often using out-dated technology) and a few very large-scale agricultural enterprises, with relatively little in between. Two per cent of the largest agricultural firms (with annual revenues of more than one billion rubles – around $15 million) account for 46.5 per cent of total agricultural revenues from the sale of goods, services and labour. But research shows that these very large enterprises are more indebted and less profitable than many smaller firms.

Russia’s agricultural progress in recent years has been based on importing higher quality seeds, animal breeds, technology and equipment from the West. Meanwhile, there has been significant under-investment in agricultural science and education in Russia. In 2013, agricultural science in Russia received $268 million; in the US, it received $16 billion. The result is a long-term shortage of qualified specialists.

The state’s role in the agricultural sector in Russia also hinders its development: the Ministry of Agriculture, regional governors and the Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Supervision (Rosselkhoznadzor) operate in non-transparent ways, impose burdens on farmers, and do little to help Russia develop an internationally competitive agro-industrial sector,

The government may succeed in making Russia a grain-exporting powerhouse, as it was before World War One, but that will not transform the country’s economic prospects. Agriculture makes up less than five per cent of Russian GDP. Though the OECD forecasts increases over the next decade in the area under cultivation and yields per hectare for many commodities, it does not foresee dramatic changes in agriculture’s share of the economy.9 According to the Centre for Strategic Research, Russia’s share of global food exports in 2016 was 1.2 per cent; if it carries out serious structural reforms, in the most optimistic scenario it will be two per cent by 2024. Agriculture is not going to rival the role of oil and gas in the Russian economy, therefore.

If it is at all serious about modernising and diversifying the economy, Russia needs to invest more in education: it cannot live on the scientific and technical legacy of the Soviet Union for much longer. Spending on basic science was cut at the end of the Soviet era, and has never recovered. Despite a fall in the defence budget in 2017, Russia still spends more on defence, security and law enforcement (more than 6 per cent of GDP) than its economy can sustain, at the expense of sectors that would contribute more to its economic development and long-term prospects.10 While its spending on tertiary education, at 1.1 per cent of GDP in 2015, is close to the EU average of 1.3 per cent, spending on basic education is much lower. In 2015, Russia spent only 1.9 per cent of GDP on education from primary to post-secondary but non-tertiary level, compared with an EU average of 3.4 per cent.11

Russian economists unanimously believe that structural and institutional reforms are the sine qua non for sustainable economic growth in Russia (and every official in the current Russian establishment would agree with them). Such reforms should include the introduction of modern management techniques for running the state, ensuring real independence of the courts, re-orientation of budget expenditure from unproductive areas (above all, security and defence) to productive sectors (such as investment in infrastructure and human capital), modernisation of the system of social welfare, and a radical reduction in the state’s share of the economy.12 But nearly all Russian economists and officials anticipate that, under the present authorities, such reforms will not be implemented.

Putin’s economic dilemma is that as long as oil and gas prices and demand hold up, the incentives to carry out far-reaching structural reforms are limited; but when prices fall, as they did in 2014-16, the surplus that could be invested to mitigate the social effects of reforms disappears. Structural reforms can be expensive, are politically risky (because groups that lose out may cause problems) and may in the short term even reduce output and employment. Even in the hydrocarbons sector, investing in more extraction by conventional means brings quicker returns for Russian firms than investing in improving technology; as a result, some innovations in drilling and extraction techniques researched decades ago by Soviet scientists have ultimately been exploited by US companies, rather than in Russia.

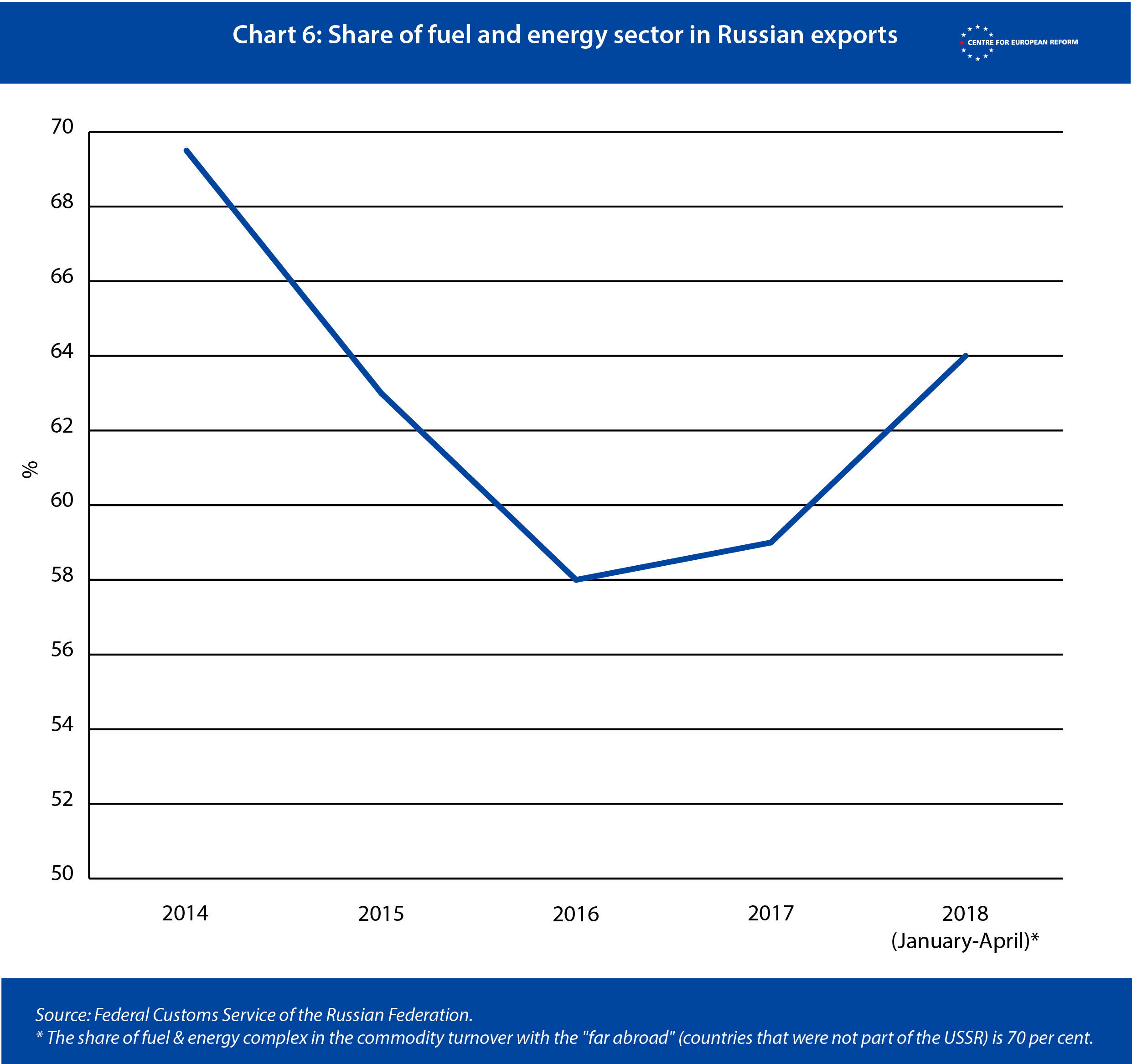

So far Putin has preferred to use the rhetoric of economic modernisation while as far as possible avoiding changes that would upset either the rentier class who benefit from controlling the hydrocarbons sector or ordinary Russians, who have continued to support him. The share of the fuel and energy sector in Russia’s exports tells its own tale: after falling with oil prices between 2014 and 2016, it has since risen from 58 to 64 per cent of the value of exports, in contrast with the May decree’s aim of increasing non-resource exports (Chart 6).

There is one exception to Putin’s aversion to risky reforms: he has pushed on with changes to the pension system that raise retirement ages, despite the negative impact on older citizens from whom he draws significant support. When Putin tried to reduce various benefits to pensioners in 2005, he backed away in the face of street protests. In 2018, despite popular protests in many cities across Russia, he made some compromises with opponents, but he did not give up the fundamental elements of the reforms. Though he did not raise the retirement age for women as far as planned (it will go from 55 to 60, not the original target of 63), he has raised the retirement age for men from 60 to 65. Putin seems to have been convinced by his economic advisers that pension reform is essential (over the next few years, a significant deficit will appear in the pension fund, unless retirement ages rise). He has taken action early in his term of office, perhaps hoping that people’s anger will dissipate quickly. And he has not left it to the unpopular Medvedev to explain the reform, making an unusually detailed technical address to the nation to set out the case, based on demographic change in Russia.13

In his agenda-setting article ‘Three Tasks for Two Years’, former reformist finance minister Aleksey Kudrin offered a softer set of conditions for higher than average growth rates, including reconfiguration of state governance, a focus on new priorities in development (such as innovation and skills), transparency and predictability of economic policy.14 But the entire record of the preceding years shows that, for the current Russian president, these tasks – even in such softened form – would most probably be unachievable.

The make-up of the new Russian government appointed by Putin after his inauguration confirmed emphatically that no ‘breakthroughs’ were to be expected. The way the government was put together showed clearly its non-political character. It has a complicated structure, with ten deputy prime ministers and 21 ministers whose functions are not always clearly delineated. Prime Minister Medvedev was only partly involved in the process of forming the Government (most ministers still feel they are Putin’s appointees). It does not look like a consolidated team. This is not an entirely technocratic government; it is a mixture of well-qualified professionals and managers and people whose main virtues consist of affiliation to the top power, strong loyalty and well-developed private ties to Putin and those around him.

The essence of Putin’s activity over almost two decades has been to improve the country’s steerability.

Konstantin Gaaze, an expert from the Carnegie Moscow Center, describes the new cabinet as “a weak government with strong ministers”.15 And he predicts that “some real functions will flow away from the government to the special services or to the [Central] Bank while some others will be allotted to the State Duma [lower house of the Russian legislature] and the expert institutes. But there will no longer exist a government as such”. That is, there will be no collective capable of and empowered to develop the conditions for advanced growth on a national scale.

The country’s development, however, has always been a secondary objective for the current Russian authorities; they talk about ‘development’ as part of an image-building effort – because the population thinks that the authorities ought to be concerned about it – rather than because they intend to do anything serious about it. The essence of Putin’s activity over almost two decades has been to improve the country’s ‘steerability’. This was precisely why he became president after Yeltsin – to assert control as Yeltsin had failed to, and rein in the intractable Duma, the regions and business. Having successfully accomplished this task, he is now building up coherently what he believes to be an ideal system of governance: a fairly simple structure, with a single centre serviced by an elite that looks like a large family; a system that does not recognize other top constitutional authorities – be they executive or legislative – as real powers, apart from the president himself.

The authorities will do what they can to maintain economic well-being, in order to ensure internal political stability and national sovereignty. They probably assess, judged on the history of the last two decades, that even if they do not achieve a dramatic increase in the growth rate, provided that they make some progress towards their targets, they can avoid serious social unrest in the – relatively short – timeline of the next six years.

What hope for export-driven growth?

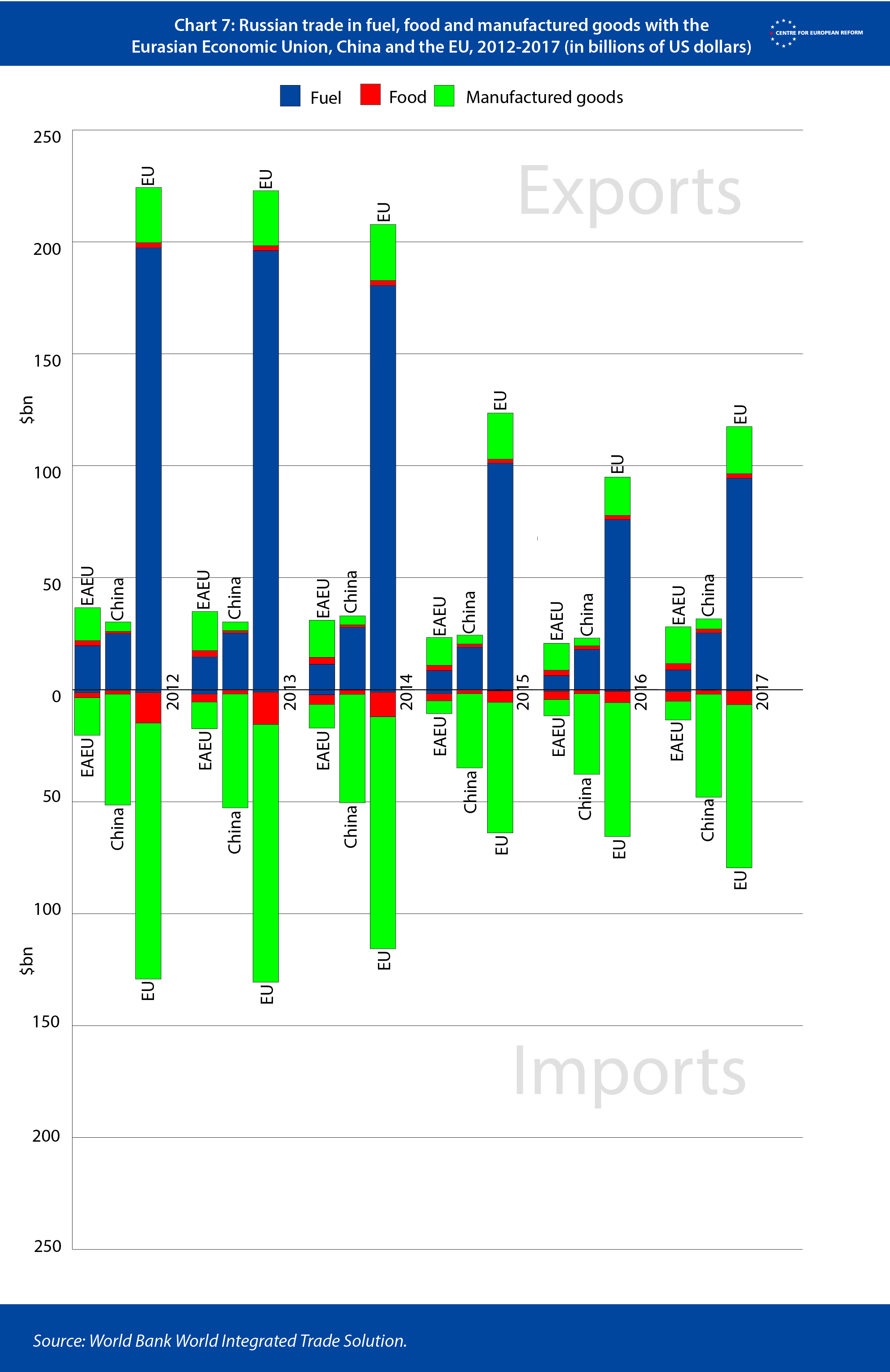

Trends in Russia’s foreign trade also support the thesis that there is unlikely to be a sudden surge in growth. A sharp increase in oil prices might change the picture somewhat; but the dollar value of Russia’s chief exports to its main trading partners, China, the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) declined every year from 2012 to 2016, before recovering slightly in 2017 (Chart 7).16 Russia’s exports of fuel, food and manufactured goods to the EU were 48 per cent lower in 2017 than in 2012. On the import side, Russia began to import more from its partners again in 2016, but imports from the EU, hit by the sanctions imposed from 2014 onwards, were still almost 40 per cent lower in 2017 than in 2014.

Though Russia held the presidency of the EAEU in 2018, the organisation’s role in Putin’s plans for the next six years seems to be limited. The May decree instructs the Russian government to develop an effective division of labour and co-operation in production in the EAEU framework (that is, the sort of integrated cross-border supply chains that the EU’s internal market have facilitated elsewhere in Europe), with the goal of increasing mutual trade and stocks of mutual foreign direct investment by 150 per cent; and to complete the common markets in goods, services, capital and labour and the removal of barriers to economic co-operation. But when officials met under Medvedev’s chairmanship on June 18th to discuss the implementation of projects to increase Russian exports, the role of the EAEU was not mentioned at all.17

Despite this apparent neglect, intra-EAEU trade increased significantly in 2017. But this came after four years of decline, and still only takes trade within the bloc back to 80 per cent of its level in 2013. With GDP growth in the EAEU as a whole of 1.9 per cent in 2017, and with Russia accounting for almost two-thirds of EAEU GDP, Russia will have to look to the rest of the world for growing markets.

In relation to manufacturing exports, the only sector in which Russia remains a world leader is armaments. It was the second largest arms exporter globally, behind the US, from 2013 to 2017.18 According to one estimate, the defence industry accounts for about one-third of employment in manufacturing.19 But exports in 2013-2017 were 7.1 per cent down on exports in 2008-2012.

Russia’s arms exports are vulnerable to competition. The West is challenging it in important markets such as India (which accounted for more than one-third of Russian arms exports in 2013-2017, but is also an increasingly lucrative market for the US and others); and China – partly by copying Russian technology – is becoming a competitive supplier in Asia and Africa. Russia’s defence industry has survived for a long time on a Soviet legacy of high quality research and development and technology. But it is proving hard to develop next-generation technology, and to recruit and train the scientists and engineers needed if Russia is to innovate as its competitors do.20 And even if Russia could deal with this weakness, success in defence sales would not transform Russia’s economic future. In 2013, when Russian arms exports were almost $16 billion, that still amounted to less than one per cent of Russian GDP. Whatever it does to strengthen its armaments sector, therefore, Russia needs to also invest in civilian industry.

If there is a bright spot for Putin in relation to trade, it is that Russia’s import ban on food and agricultural products from the EU and other Western countries has, as he hoped, provided a stimulus for domestic production in Russia, with some knock-on effects on exports. Russian exports of agricultural goods were around 15 per cent higher by value in 2017 than in 2013; over the same period, US agricultural exports declined slightly and EU agricultural exports were effectively stagnant. But Russian agricultural exports still amounted to only $29.5 billion in 2017, compared with EU and US agricultural exports of $175 billion and $163 billion respectively.

At the June 18th 2018 government meeting, Medvedev said that the government’s task was to create a high productivity, export-oriented sector in the economy, in particular in manufacturing industry and agriculture. Putin has called for Russian exports to reach $250 billion by 2024, about twice the current figure; Medvedev himself noted in a discussion of export policy on April 25th 2018 that Russian exports would have to grow at a rate of almost 10 per cent a year to achieve that target, while the WTO forecast was that global exports would only grow by 2.5 per cent a year.21

Putin’s people problem

Putin has been talking about Russia’s demographic problems for many years. The death rate has exceeded the birth rate in every year except three from the early 1990’s onwards. The situation in the countryside is particularly stark: while urban populations saw more births than deaths from 2012 to 2016, there has not been a single year since the collapse of the Soviet Union when the birth rate in rural areas was higher than the death rate.22

With a shrinking population that includes a larger proportion of unhealthy pensioners, Russia risks stagnation.

Life expectancy in Russia has been rising, from 69 in 2010 to 72 in 2017. But there remains a large gap between male life expectancy at 68 and female life expectancy at 78. Still more troubling is the healthy life expectancy (HALE) at birth, that is, the years that a person can expect to live in full health. In 2016, this was 63.5 years overall, but only 59.1 for men (this compares with an overall HALE for China of 68.7, and 68.0 for men).23 Though Russians’ HALE has increased significantly (from 58 overall, and 52.5 for men, in 2000), the May decree target of 67 overall still seems some way off. Against this background, protests against the government’s plan to increase the retirement age to 65 for men (and 60 for women) are understandable: many will be unable to keep working until they qualify for their state pension, and are likely to die soon after they collect it. While many Western societies are also keen to keep older people in the work force for longer, in most cases they are also targeting a healthier group: the UK’s HALE, for example, is 71.9.

The May decree also calls for an increase in Russia’s fertility rate (the number of live births throughout a woman’s childbearing years) to 1.7 – a relatively undemanding target, since it was exceeded in each year from 2013 to 2016 (the figure in 2017 was 1.62). Merely to maintain the size of the population, however, requires a rate of more than 2.0 (to take account of infant and adolescent mortality), so the number of Russians seems doomed to shrink further.

Low birth rates and high death rates create a number of challenges to Russia’s economic development and its place in the world. Population growth would not automatically lead to rapid economic growth, especially not if achieved through an increased birth rate, but it would help. Putin and Medvedev have not managed to increase growth through the alternative method of structural reforms leading to higher productivity and more efficiency – in other words, Japan’s (partial) solution to its ageing population. With a shrinking population that includes a larger proportion of unhealthy pensioners, Russia risks stagnation.

Russia is importing labour, and could increase immigration still further to fuel economic growth. Russian official statistics show that net migration from former Soviet states between 2000 and 2016 was 3.3 million. An unknown number of migrants from the former Soviet Union work illegally in Russia; according to one estimate, even after the Russian government introduced simplified procedures for them to regularise their status in 2007, only 35-40 per cent of migrants working in Russia had authorisation to do so.24 As a result, migrants are vulnerable to organised criminals exploiting them, and to discrimination and sometimes violence from local authorities, extremist groups and a suspicious or hostile population.

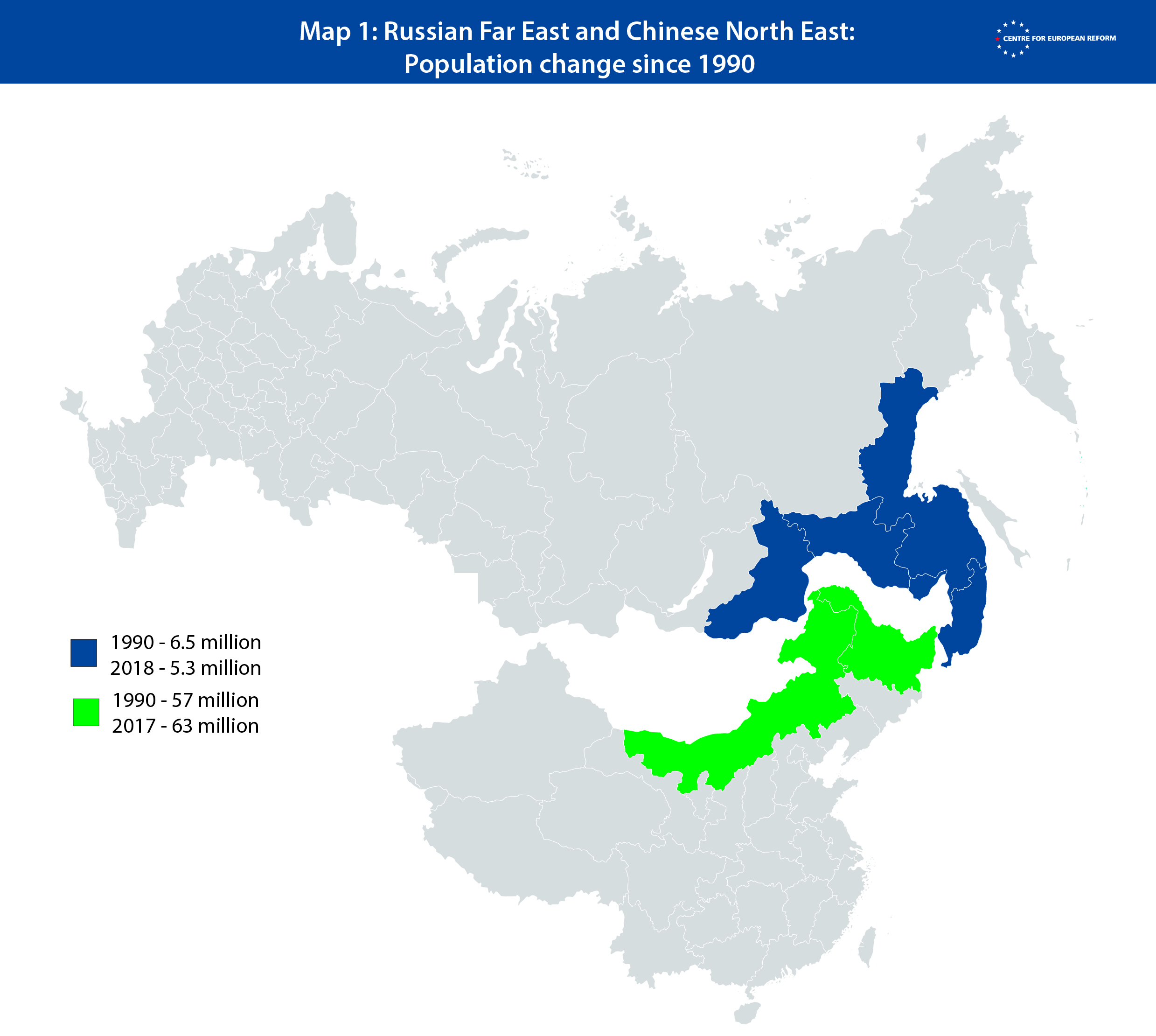

Russia’s declining population also poses strategic problems, particularly in the Far East. Russia’s overall population was about two per cent smaller at the start of 2018 than in 1990; but in the five regions bordering on China’s North East, it had shrunk by almost 19 per cent, leaving 5.3 million Russians facing more than 60 million Chinese in the regions across the border.25 Even though Russia and China have settled all their border disputes, many Russian military and political figures have worried since the break-up of the Soviet Union that large numbers of Chinese would migrate into these resource-rich but under-populated eastern regions, turning them into de facto Chinese territory. As late as August 2012, Medvedev warned against “excessive expansion by bordering states” and “the formation of enclaves made up of foreign citizens” in the Russian Far East – though Russian official statistics record net migration from China of fewer than 20,000 people from 2000 to 2016.26

Putin’s person problem

Repopulating the Russian Far East is a task of generations. Putin faces a more pressing problem, which will get worse throughout his term of office: who will rule Russia after May 2024? Under the current constitution, the president can only serve two consecutive terms; given that Putin will be 72 in 2024, it seems unlikely that he could repeat the stratagem of 2008, and arrange to be succeeded by a compliant ally who would step down in favour of a 78-year-old Putin in 2030. Putin could allow free elections in 2024 to choose his successor, but that would be entirely at odds with his efforts throughout his years in power to manage the electoral process, and to exclude ‘undesirable’ candidates. That implies that he has three main options:

- Do as Yeltsin did in 1999, and find his own Putin – someone who would guarantee his safety, and perhaps those of his close associates, after his retirement. That may have been Putin’s intention in 2008, when he swapped places with Medvedev, becoming prime minister while Medvedev kept the presidential seat warm. If so, for some reason he decided that Medvedev was not the man to protect him in the long term.

- Change the constitution to allow him to run again. This has been common practice in the former Soviet Union, used in Belarus, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to keep their leaders in power beyond two terms. Putin could follow this route, but he said in 2017 that he did not intend to change the constitution to allow him to stay in office.27 Commentators have noted that Putin often looks bored while taking part in the set-pieces of the presidency, such as his annual news conference, and speculate that he might want to retire.28 On the other hand, after the election in March, a former minister told Time magazine that Putin “can’t imagine life without power”.29

- Find a new position from which he could exercise power. Again, Kazakhstan might provide a model – or even two. In 2010, a law declared President Nursultan Nazarbayev ‘Leader of the Nation’, giving him control over government policy even after he might eventually leave the presidency, as well as immunity from prosecution and protection for his assets and those of his family. In case that was not enough, in 2018 another law made Nazarbayev chairman for life of Kazakhstan’s Security Council, which is responsible for co-ordinating national security policy, defence and internal security capability, and protection of Kazakhstan’s international interests. Putin created a powerless ‘State Council’ as an advisory body in 2000, with regional leaders and representatives of pro-system political parties as members; there has been speculation in Russia that he might give it new authority to enable him to exercise effective power through it after 2024, while delegating much of the hum-drum work of the president to his successor. Putin himself, however, has said nothing publicly about such a plan. Alternatively, he could repeat the 2008 experiment, find a compliant president and exercise power from the prime minister’s office.

By building a system that relies on him to keep it running, Putin may have imprisoned himself in the Kremlin.

Perhaps Putin fears that talking about leaving office would immediately make him a lame duck and trigger infighting among the elite. If so, he may already be too late: even before the March 2018 election Igor Sechin, the powerful chairman of Rosneft, and a leading representative of the siloviki faction (made up of current or former KGB or military officers), seemed to be ‘on manoeuvres’, securing the imprisonment of former economy minister Aleksei Ulyukayev in 2017, after the latter had tried to impede Sechin’s plans for expanding Rosneft. But Putin has in the past clipped the wings of ambitious subordinates; there is no guarantee that Sechin will end up as ‘Tsar’, or even as the king-maker. Equally, there is no sign that Putin wants to rebalance his team away from the siloviki who have been in the ascendant since he returned to power in 2012, and towards the economically more literate and reform-minded technocrats like Aleksei Kudrin or Central Bank governor Elvira Nabiullina.

It may be that the only way for Putin to stay in firm control and prevent intra-elite conflict is to make clear at an early stage that he will remain in charge (with whatever constitutional decorations are necessary) beyond 2024; in effect, by building a system that relies on him to keep it running rather than on viable independent institutions, he may have imprisoned himself in the Kremlin for the foreseeable future. But the longer he stays in power, the more he risks the fate of Communist Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, who led the Soviet Union from 1964 until 1982: his latter years were characterised by economic stagnation, and he himself became an object of ridicule, epitomising a system that could not renew itself.

Foreign and security policy: Six more years besieged?

Whether Putin decides to stay in power beyond 2024 or not, it seems likely that his world view will have a lasting impact on Russia’s relations with its neighbours and other world powers. Russian national security policy documents (and the rhetoric of the authorities) have portrayed Russia as a fortress besieged by enemies for at least the last decade, harking back to an image of Russia standing alone against a hostile West that Lenin used during the Russian civil war. It became the dominant image after the protests against the authorities in 2011 and 2012, which Putin blamed on the West and in particular on Hillary Clinton.

The Kremlin’s experience over the last four years is that pursuing a daring and radical foreign policy, with the stakes always rising, has in reality neither led to a significant degree of political isolation for Russia, nor noticeably drained its resources. At the same time, the regime has been able to use external turbulence and the perception of threats from abroad as a unifying force to ensure internal stability.

At a time of domestic economic hardship, an external threat (real or imagined) encourages the population to ‘rally to the flag’; it justifies a high level of military and security expenditure; and (by putting the blame for problems on Western sanctions) it explains why a country with such abundant resources still suffers so much from poverty.

As the March 2018 elections clearly showed, it is much easier to be the president of a nation at war, provided at least that the scale of the conflict is such that it does not demand serious sacrifices from the population: today’s Russians are not as willing to die for the Motherland as those who fought in the ‘Great Patriotic War’ from 1941 to 1945. Putin has carefully concealed the casualties of fighting in Ukraine and minimised the involvement of Russian ground troops in Syria. He portrays ‘Russian values’ as under threat from the West; opposition to European decadence is part of his narrative for consolidating the population around him, but it was not something he focused on in his first and second terms of office: it may not be a deep-rooted belief system, even for him. And despite the alleged ‘Western threat’, the Russian elite (including some of those close to Putin) continues to store its money in the West and educate its children there.

Despite the alleged ‘Western threat’, the Russian elite still stores its money in the West and educates its children there.

Whether or not Putin genuinely believes in the wickedness of the West, he would like his Western interlocutors to take it as read that his grievances are justified and to accept that the West must somehow pay for the errors in its Russia policy. He has had some success with Trump: at the press conference after their Helsinki Summit in July 2018, Trump said that the US had been “foolish” in its policy towards Russia. Some Western leaders, especially those in Central Europe and the Baltic States, have been less easily persuaded.

The pre-election interview that Putin gave to the American TV Channel NBC in March 2018 focused on relations between Moscow and Washington. But it also provided a clear idea about the Russian leader’s general approach to foreign policy issues, and to dialogue with foreign partners.30

Putin set out an explanation of the recent history of US-Russian relations in terms of constructive suggestions from Russia that were rejected by the US – a continuous, ritual exchange rather than a substantive dialogue. The aim of contacts with the US, from Putin’s perspective, was not so much to take decisions collectively, as to establish Russia’s international stature. The exchanges comprise not only occasions on which Russian and Western representatives talk to each other, but demonstrations of power to impress a Western audience. Russia’s military presence in Syria or the introduction of modern arms systems into Russia’s arsenal, announced by Putin in his ‘Message to the Federal Assembly’ in March 2018, were also, in the first instance, remarks aimed at his Western counterparts.

Does Putin regard Western countries as partners, or adversaries? He uses the words “partner” or “partnership” often enough – 14 times in his NBC interview. But in Putin’s lexicon that is no more than a respectful reference to a foreign interlocutor. It does not imply an identity of values, a point often misunderstood by Western leaders. The history of Moscow’s relations with the EU bears witness to this.

Moscow saw the EU-Russia relationship, as it evolved from the Partnership and Co-operation Agreement of 1994 to the Partnership for Modernisation of 2010, as a ritual leading to mutually respectful dialogue. The Kremlin’s view was that such a dialogue should guarantee the parties freedom of action where their areas of interest did not overlap, while creating a framework for them to resolve their differences should their interests clash. In Moscow’s view, the contractual relationship excluded any attempts to advance the EU’s political values inside Russia.

That view was at odds with that of the EU, which saw the various agreements as leading to broad convergence – understood as meaning Russia gradually adopting EU norms and standards, rather than both parties compromising. The Kremlin regarded such a partnership, based on claimed ‘shared values’ where none existed, as meaningless at best and dangerous for Russia’s current system at worst.

By 2014 both sides had lost any remaining illusions about respect for each other’s areas of interest, or convergence. In 2018, the pre-election preview of Russia’s new weapons systems that Putin offered the Federal Assembly ended with the phrase: “Nobody listened to us. Listen now”. It sounded like the tagline for a blockbuster about the birth of a new global evil.

Despite this air of belligerence, Putin would like to move on – or rather back, to the kind of business-oriented relationship between Russia and the EU that was characteristic of the first years of his presidency. He would like the EU to focus less on Russia’s behaviour in recent years, and more on the fact that it remains a huge market, one of the world’s largest sources of raw materials, and an infrastructure hub between Europe and China with high potential. Putin has already shown his ability over the last 18 years to use a variety of tools to help Russia regain some of the international influence that was lost with the break-up of the Soviet Union; he would like to continue the process during the remainder of his time in office.

Putin has proved to be adept at exploiting the divisions within and between Western countries, by overt and covert means

First, Putin has shown that Russia can engage with the other major powers to tackle shared problems when it is in its own interests to do so – notably in the negotiations to help curb Iran’s nuclear weapons programme. The permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany worked together effectively to reach an agreement with Iran in 2015; and when Donald Trump announced that the US was withdrawing from it in May 2018, Russia continued to work with the other members of the group to preserve the deal.

Putin has assiduously cultivated President Xi Jinping in an effort to strengthen the partnership between Russia and China, particularly in opposition to Western intervention in other countries’ affairs. Russia and China are often (though not always) tactical allies at the UN. Putin has responded to Xi’s signature ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI), with its large-scale infrastructure investments in Russia’s neighbourhood, by trying to strengthen the links between the EAEU and the BRI. The security relationship between Moscow and Beijing has also warmed up. Less than a decade ago a senior Russian general judged the threats to Russia from NATO and China to be comparable; but in September 2018, 3000 Chinese troops took part in Russia’s large ‘Vostok’ military exercise in Siberia and the Russian Far East.31

Regardless of Putin’s motives, he has also continued to talk to French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel about the conflict in Ukraine. Because the West sees the Minsk process (so-called because the agreements that put an end to the most active phase of the conflict were finalised in Minsk) as ‘the only game in town’ in the pursuit of a lasting peace in Eastern Ukraine, Putin can portray himself as a disinterested mediator rather than a party to the conflict. He has been able to persuade many Western politicians and commentators to see the conflict as a result of ‘separatism’, which Ukraine needs help to resolve internally, rather than an inter-state conflict in which Russian forces are fighting on the territory of a neighbouring country.

Second, Putin has sometimes acted decisively to pursue Russia’s interests while the West has hesitated. This is clearly the case in Syria, where the US and its allies insisted that Bashar al Assad could not remain in power, but did not make any effort to overthrow him. As a result, when Putin committed Russian forces to keep Assad in power, he became the key player in international efforts to bring the war to an end. Though the US and its allies have been involved in fighting the so-called Islamic State in the region, they have largely been marginalised in the diplomatic moves led by Russia, Iran and Turkey to broker a solution to the Syrian civil war. Putin has been remarkably successful in maintaining good relations with most of the external parties involved in the Syrian conflict: Iran (an ally in propping up Assad); Turkey (despite tension over traditional Russian support for the terrorist organisation the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and over Turkey’s shooting down of a Russian fighter aircraft in December 2015); Saudi Arabia (a leading backer of Assad’s opponents); and Israel (pre-occupied with keeping Iran and its proxies away from Israel’s borders).

Third, Putin has proved to be adept at exploiting the divisions within and between Western countries, by overt and covert means. Whatever US Special Counsel Robert Mueller uncovers about alleged collusion between Trump’s presidential campaign and Russian interests, it is clear that the Kremlin saw Trump’s election as preferable to Hillary Clinton’s. In pursuit of their aims, they found it easy to manipulate a deeply divided America, in which (for instance) supporters of the right to bear arms were willing to accept Russian backing if that helped them to attack their domestic opponents; or Russian social media accounts could organise demonstrations in Texas by both supporters and opponents of Islam.32

Even though Trump has been unable to resist Congressional pressure to impose more sanctions on Russia, in response both to the Ukraine conflict and to the use of chemical weapons against the former spy Sergey Skripal in the UK, Trump’s hostility to NATO and his trade wars with traditional US allies including Canada and the EU are certainly helping to increase Russia’s relative strength and influence. In a recent opinion poll in Germany, 69 per cent of respondents said that ‘a more dangerous world because of Trump’s policies’ was their top worry; Putin’s policies were not among their top 20 concerns, despite the Skripal case and the continuing conflict in Ukraine.33

Within Europe, the Russian intelligence services and Russian business figures with close ties to Putin have put considerable effort into building up links with populist parties, including the ‘National Rally’ in France (formerly known as the ‘National Front’), the Lega and the Five Star Movement in Italy and the Freedom Party in Austria (which signed an agreement on collaboration and co-operation with Putin’s ‘United Russia’ party in 2017).34 Some of these parties have since become very influential in their respective countries: the Lega and the Five Star Movement formed a coalition government in May 2018, while the Freedom Party is a junior partner in Austria’s coalition government and provides the ministers of defence, interior and foreign affairs. The Kremlin’s views have even found a few sympathetic ears within the mainstream parties in Western Europe, where there are politicians of both right and left who accept the argument that NATO and the EU have provoked Russia, and have only themselves to blame for the conflict in Ukraine and other sources of tension.35

Sanctions apart, there is reason for Putin to feel that his foreign and security policy is in good shape.

Though the success of the pro-Russian populist parties has not resulted in the lifting of EU sanctions, Putin may be able to use their lack of enthusiasm for restrictive measures to his advantage. There are six draft bills imposing additional sanctions on Russia under discussion in the US Congress. The US may not in the end adopt such measures; but the prospect of tougher sanctions is dividing the US from its European allies and US business from Congress.

The EU has long objected to US sanctions with extra-territorial effect. US measures would have an impact on Russia, but they would also hit EU firms. In the US itself, energy firms are lobbying hard against aspects of the proposed sanctions that would not only prevent them from investing in Russia but from dealing with or being in consortia with Russian oil and gas firms in third countries.

Sanctions apart, there is reason for Putin to feel that his foreign and security policy is in good shape: even if the defence budget had to be cut in 2017, and is likely to remain flat for a few more years, the armed forces are – for now – stronger than at any point since the fall of the Soviet Union; his adversaries, though increasing their defence budgets, have shown little political will for confrontation; and he has been able to find willing allies in most of the main Western countries. He has also shown that when an international crisis breaks out, being able to obstruct the search for a solution will get him a seat at the table just as easily as being able to contribute to resolving the problem – and often at lower cost.

Managing tension between Russia and the West: Talking therapy

Putin’s foreign policy actions in Syria, Ukraine, and elsewhere have led to economic sanctions and condemnation from the West, but he has remained on the front foot. The West, meanwhile, has often been unable to take the initiative, and has had little option but to react to Moscow’s moves and narrative. Putin’s message to the West in his March 2018 NBC interview ended: “Listen, we should sit down and talk it over in order to get things straight… But we are ready to discuss any matter, be it missile-related issues, cyberspace, or counter-terrorism efforts. We are ready to do it any moment… We will be ready the instant our partners are ready”. Putin could say this, comfortable in the assurance that the West would be divided over whether to treat his offer as a serious attempt to find areas of common interest, or a cynical attempt to make himself look like ‘the good guy’, without making any concessions on important issues.

Though these are dangerous times in relations between Russia and the West, the world is not facing a full-scale ‘Cold War’. For one thing, Moscow cannot offer an alternative societal model in the way that it could in the Soviet era; it can only exploit local alternatives to the prevailing order, whether populist euro-pessimism or Trumpian nativism, to undermine its adversaries. Nor is a full-scale arms race likely – or at least, not between the US and Russia. There are simply not enough resources available in Russia, as its now-declining defence budget shows. Over the last three decades of the ‘Cold War’, the US spent on average between two-and-a-half and four times as much on defence per year as the Soviet Union. In 2000, the US military budget was 60 times larger than Russia’s. By the 2010’s, the multiple had shrunk back to 10, but Moscow has been unable to get any closer to matching American defence spending than that. It is unlikely that Russia will be in a position to do so in the foreseeable future either, particularly as Trump is expanding the US defence budget again, after real-terms declines under Barack Obama.

European leaders have considerable experience of dealing with the Russian president and his team, and most of them have probably found it exhausting and unproductive. The EU shares some of the blame for this state of affairs. Over the past two decades, the EU has struggled to produce its own realistic and unified agenda for dialogue with Russia, and then to keep its Russian interlocutors focused on it. Europe was not – and still is not – sure what it wants from Moscow, or what it can realistically hope to get.

Policy-makers dealing with Russia must assume that nothing will ever change, but everything might change overnight.

Western policy-makers dealing with Putin’s Russia have to assume both that nothing will ever change, and that everything might change overnight. They need policies that increase the West’s resilience, on the assumption that Putin’s successor will also pursue policies to increase Russia’s relative power vis-à-vis the West. That work is already underway: European countries are (slowly) increasing their defence spending, investing more in cyber security and thinking about how to counter disinformation and influence operations. They are taking more seriously the need to identify flows of money from Russia, and to understand the extent to which wealthy Russians may work at the behest of the Kremlin to shape political debate in the West. Despite grumbling from some countries in Europe, and from some businesses, Western sanctions remain in place, not at a level that would threaten Russia’s economic stability, but enough to be an irritant to the leadership.

But Western governments also need to keep the door open to improvements in relations, and to build links to Russians who might facilitate them, under different leadership. Isolating Russia diplomatically is neither desirable nor possible: it is not North Korea but a permanent member of the UN Security Council and a member of the G20. Engagement cannot mean a return to business as usual, however, or dialogue only on Putin’s terms. Talking to the Russian authorities where it is mutually beneficial or even essential, without signalling to Putin that he has weathered the storms caused by the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the US election interference of 2016, will demand a difficult balancing act.

The West did a good job of concerting sanctions policy in the immediate aftermath of the annexation of Crimea. The Obama administration put considerable effort into keeping like-minded countries aligned, even if it proved impossible to ensure that the sanctions of all countries remained identical. The Trump administration, with its idiosyncratic Russia policy and Trump’s personal hostility to the EU, has struggled to maintain the same level of co-ordination. The foundation for any productive dialogue with Russia has to be a firm and united Western position; without it, Putin will have every opportunity to exploit the divisions for his own ends.

Western allies need to agree among themselves what facets of Russian policy are matters of principle and not open for discussion, and where there might be room for co-operation with Moscow. As in the Cold War when Western countries refused to recognise the annexation of the Baltic States, for example, they should now reinforce the message that the annexation of Crimea is illegal and that it can never be a subject of negotiation; but that should not rule out discussions on other matters.

For its part, Russia also needs to consider whether its economic and political interests would be better served by developing more co-operative relations with its neighbours. Russian foreign policy objectives often seem geared to giving neighbouring countries a choice between being in Russia’s orbit, or being weak and divided. That is a viable strategy for a country that does not trust its neighbours to act in ways that bring mutual benefit. But does Russia need to feel quite so threatened? The data shows that defence spending in the former Warsaw Pact countries and the Baltic States was higher in 2003, before most of them joined the EU and NATO, than in 2013 (though it has risen rapidly since Russia’s intervention in Ukraine).36 The Central European countries also traded more with Russia after joining the EU than before, presumably as a function of their increasing prosperity: trade more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2014, from $19 billion to $82 billion.37 In the long term, the policy of dividing and weakening neighbouring countries decreases the scope for building trust between Russia and the West, and therefore the opportunities to develop economic and other forms of mutually beneficial co-operation.

What to talk about?

Relations between Russia and the West are likely to be characterised by distrust, mutual fear and confrontation for the remainder of the Putin era, and probably for some time after. But as the Cold War showed, both sides may accept that it is in their interests to discuss certain issues, even if agreement on what to do about them has to wait till the political situation has changed fundamentally. There may also be some areas of mutual interest which are less politically controversial, in which both sides can benefit from co-operation without necessarily wanting or needing to agree on specific actions.

Top of the list of issues that must be discussed, regardless of whether agreement is possible in the foreseeable future, is international security. The most urgent item is nuclear arms control. The US has announced its intention to withdraw from the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty (the INF treaty), blaming Russian violations for its decision. The treaty, signed in 1987, eliminated a whole class of Soviet and US weapons that were perceived as particularly threatening because they could strike targets in Europe and the Western Soviet Union with very little warning. The West should not give it up without further efforts to persuade Russia to change course. Russia also has its own concerns about US compliance with the INF treaty, at least some of which are reasonable enough to deserve a response.

Even if arms control discussions do not produce agreement, they can be a useful confidence-building measure.

In addition to the INF treaty, the New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), which entered into force in 2011, will expire in 2021 unless the US and Russia agree to extend it for a further five years. Trump has attacked the treaty, largely because his predecessor Barack Obama negotiated it. But there are reasonable questions, which the US and Russia could start to address together, about the future of strategic nuclear arms control in an era when China is still adding to its nuclear weapons stocks and will become increasingly relevant to the global nuclear balance. Russia would like to widen future negotiations, to include China, France and the UK, but is reluctant to discuss China bilaterally with the US. It should accept that Washington and Moscow need to agree at least conceptually on how to take other nuclear powers into account in future, whether or not the other states are willing to join them at the negotiating table.

The next priority after nuclear arms control should be a new effort to reduce military tension through confidence- and security-building measures, discussions of military doctrine and other efforts to increase transparency. Existing agreements have largely broken down, resulting in increased tensions every time NATO or Russia carries out a large-scale military exercise.

Under the auspices of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe and its predecessor, the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe, European countries adopted six sets of progressively broader confidence- and security-building measures between 1986 and 2011. Since then, however, Russia and the West have each alleged that the other has circumvented the agreements, for example by artificially breaking down large-scale military exercises into smaller components that no longer automatically trigger an invitation to observers, or claiming to carry out short notice ‘readiness exercises’ in order to avoid having to warn other countries in advance. They need to start talking again about their concerns and how the other side could allay them.

Rather than tearing up existing arms control and confidence-building agreements and starting again with a clean sheet, Russia and the Western allies should discuss whether problems with implementation are the result of identifiable, legitimate disagreements over interpretation or procedures, and then look at steps they could take to make the agreements work again. If there have been advances in technology or military practice since the agreements were first reached that require the texts to be amended, then both sides should be willing to explore them. British and Russian experts have laid the foundations for possible bilateral confidence-building steps, but a broader range of countries need to be involved for such measures to have a significant effect on the security environment in Europe.38 And even if ultimately such discussions do not produce agreement, they can be a useful confidence-building measure in their own right, and can lay the foundations for progress later, when political conditions are more favourable.

Informal contacts between Russia and the West might be particularly useful on issues such as military activity in space, and government-sponsored hostile cyber activity. These are emerging areas of confrontation in which there are few well-defined rules.

The UN Conference on Disarmament has been discussing how to prevent the militarisation of space in a desultory fashion since the 1980’s. In 2008, Russia put forward a draft treaty on the prevention of an arms race in outer space, while the EU proposed a code of conduct (which would not be legally binding). The US has always resisted multilateral agreements on arms control and disarmament in outer space, and the Trump administration, which wants to set up a ‘Space Force’ as a new branch of the armed forces, is very unlikely to welcome a new effort in this area. Nonetheless, the EU, Russia and the US (and others such as China) all have a lot to lose from hostilities in space, given the dependence of the civilian economy and military forces on satellite navigation and communications. It would be worth exploring privately (outside a UN forum where both sides are tempted to play to the gallery and put forward unrealistic proposals, knowing that the other side will always block them) what the concerns of the parties are about each other’s activity in space, and how they could be mitigated.

Russia and the West face a number of similar social issues and could benefit from discussing how they tackle them.

Likewise in cyberspace, all parties are increasingly vulnerable to attacks. The case of the Stuxnet virus, used against the Iranian nuclear weapons programme in 2009-2010, but inadvertently damaging systems in a wide range of other countries, shows that there is a significant risk of unintended consequences. Russia, China and other authoritarian states on the one hand and Western democracies on the other are at odds over how best to regulate conduct in cyber-space. Though internationally-accepted rules on how to deal with cyber-attacks may be far off, there is still scope to talk about acceptable and unacceptable behaviour in cyberspace, and to create more clarity about how countries might react to (for example) a cyber-attack on critical national infrastructure: would it be treated as the equivalent of an armed attack, for example?39 Some talks along these lines, involving current and former officials from Western countries, Russia and China, have already taken place and helped the parties to understand the differing concerns they have.40

Even during the Cold War, the Soviet Union and three Western countries with nuclear weapons (France, the UK and the US) worked together to prevent nuclear proliferation. Together with China, the nuclear weapons states should consider what they can do to reduce the risks of proliferation in the run-up to celebration in 2020 of the 50th anniversary of the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT). Even after the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA – the agreement ending Iran’s nuclear weapons programme), Russia and its partners are likely to share common objectives for non-proliferation, though there may be more disagreement than before on the means for addressing proliferation concerns in Iran, North Korea and elsewhere.

There may also be scope to talk about security issues and conflict resolution in regions of the world where neither Russia nor the West believe that they have vital interests at stake, such as Africa, the Maghreb, South and South-East Asia and Latin America. The Minsk process on Ukraine, the Geneva forum for discussions on Abkhazia and South Ossetia (regions of Georgia recognised as independent by Russia after the Russo-Georgian war of 2008) and the various abortive discussions on Syria have all foundered because all sides see themselves as having too many vital interests for them to compromise. But it may be easier for Russia and its partners to look at other less contentious areas more objectively, and even identify steps that they could take to tackle security problems.

Given that Russia and the West are likely to be at loggerheads over security issues, it would be worth their while to discuss other challenges that they both face and could in theory tackle together or at least in parallel, in pursuit of shared goals. One such area is energy and climate change. The EU established an energy dialogue with Russia in 2000, but suspended almost all its formal activities in 2014 as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. Nonetheless, given the importance of the EU to Russia as an energy purchaser, and Russia to the EU as a supplier, there should be scope to explore the implications for both of climate change and the global shift to a low carbon economy. Russia will not be immune to the effects of climate change, whether positive (making the economic exploitation of the Arctic easier) or negative (melting the permafrost and turning large areas of northern Russia into swamps).

Russia and the West also face a number of similar social issues and could benefit from discussing their approaches to tackling them. Though Russian life-expectancy lags behind that of most Western countries, it also faces a similar problem of a low birth-rate leaving a smaller working-age population supporting a larger retired population (the driver behind the recent pension reforms). As in the West so in Russia, migration, while mitigating the problem to some extent, creates social challenges of its own. These are issues on which Russian and Western experts could engage and exchange views on best practice, without raising difficult political issues or having to reach agreement.

In health care also, there would be scope for discussions of best practice, both of treatment and management. Russia faces an HIV/AIDS epidemic: about one per cent of the population is HIV positive, compared with a figure of 0.16 per cent in the UK; yet access to drugs is very limited. Cases of tuberculosis (TB) rose rapidly after the collapse of the Soviet Union; numbers declined again from the mid-2000’s, but cases of multi-drug resistant TB have risen. Dialogue might be politically difficult: the Russian authorities will probably reject any initiative that implicitly criticises Russia, or puts it in the position of a ‘pupil’ of the West. But it might be possible for experts to talk to each other on a more neutral footing, without giving any dialogue a political profile.

Conclusion

Neither Putin nor his Western counterparts can predict what the world will look like in 2024, but it is highly likely that the issues on which the West and Russia disagree will still be outstanding. Neither side will want to make concessions on issues that they see as matters of principle. Nevertheless, they should avoid staying in their respective bunkers. Even if there is not yet a basis for negotiation to resolve confrontation, there is a need for dialogue to reduce tensions, and to avoid accidental escalation resulting from misunderstanding each other’s motives and actions.

Putin is sometimes portrayed in the West as a great strategist with a long-term plan, but his record suggests that he is in reality a skilled tactician and a master of seizing an opportunity when it presents itself. The West’s current leaders cannot even boast that skill: more often than not, whether dealing with the economic and financial crisis or international conflicts, they have been reactive, and also slow and indecisive.

Barring some unforeseen event, Putin will be president of Russia until at least 2024. If he wants to leave office with a positive legacy, he needs a plan for the remainder of his time in power. Without a plan and the intention to implement it, he will indeed risk becoming a new Brezhnev. But the West also needs a plan for dealing with Putin, that neither leads to capitulation nor war, but lays the foundations for a stable relationship for the next five years and beyond.

2: ‘Russia foreign exchange reserves: Months of import’ and ‘United Kingdom foreign exchange reserves: Months of import’, (data for August 2018), CEIC Data, accessed January 18th 2019.

3: World Bank data, ‘Real effective exchange rate (2010 = 100)’, accessed November 12th 2018.

4: US Energy Information Administration, ‘Tight oil production estimates by play’, accessed November 12th 2018.

5: US Energy Information Administration, ‘Dry shale gas production estimates by play’, accessed November 12th 2018; ‘BP Energy Outlook: Country and regional insights – Russia’, BP.com, accessed November 12th 2018.

6: ‘Russia is Only 3 Years Away From Peak Oil, Energy Minister Warns’, The Moscow Times, September 19th 2018.

7: Lyudmila Podobyedova and Timofey Dzyadko, ‘Pribyl’ dlya podryadchikov: Skol’ko aktsionyery ‘Gazproma’ teryayut na stroykakh’ (‘Profit for contractors: How much ‘Gazprom’s’ shareholders lose on construction’), RBK (in Russian), May 21st 2018.

8: Unless otherwise noted, data and analysis in this section drawn from Natalya Shagayda and Vasiliy Uzun, ‘Tendentsii razvitiya I osnovnye vyzovy agrarnogo sektora Rossii’ (‘Development trends and main challenges of the Russian agrarian sector’), Tsentr Strategicheskikh Razrabotok (Centre for Strategic Research), November 2017.

9: OECD, ‘Medium-term prospects for major agricultural commodities 2017-2026: Russian Federation’ (undated, data drawn from OECD-FAO ‘Agricultural Outlook 2017-2026’).

10: Mark Galeotti, ‘STOLYPIN: Russian security spending and the biggest threat to Russia’, BNE Intellinews, November 25th 2016, and Russian Federal State Statistics Service, ‘Structure of elements of GDP use’, accessed October 31st 2018.

11: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Education spending (indicator)’, accessed October 30th 2018.

12: Aleksey Kudrin and Ilya Sokolov, ‘Byudzhetniy manyovr i strukturnaya perestroika rossiyskoy ekonomiki’ (‘Fiscal manoeuvre and restructuring of the Russian economy’), Voprosy Ekonomiki No 9 (in Russian), 2017.

13: ‘The President’s address to Russian citizens’, Kremlin website, August 29th 2018.

14: Aleksei Kudrin, ‘Tri zadachi na dva goda’ (‘Three tasks for two years’), Kommersant (in Russian), March 21st 2018.

15: Konstantin Gaaze, ‘”Takogo, kak Putin”. Pochemu Rossii nuzhen nezavisimiy prem’er’, (‘“Someone like Putin”. Why Russia needs an independent prime minister’), Moscow Carnegie Center (in Russian), May 4th 2018.

16: The Eurasian Economic Union, with Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia as members, began operations on January 1st 2015. Armenia joined it officially a day later; Kyrgyzstan followed on August 12th 2015.

17: ‘Zasedanie prezidiuma Sovyeta pri Prezidente Rossiyskoy Federatsii po strategicheskomu razvitiyu i prioritetnym proyektam’ (‘Meeting of the presidium of the President of the Russian Federation’s Council on strategic development and priority projects’), Russian government portal (in Russian), June 18th 2018.