Reviving European policy towards the Western Balkans

- The EU has sought to stabilise and integrate the Western Balkans countries through enlargement, but this process has now stalled. Montenegro’s and Serbia’s accession negotiations have made little progress since they started in 2012 and 2014 respectively. The EU has not started talks with Albania and North Macedonia, as it had promised to. Meanwhile, Kosovo remains far from starting talks and Bosnia-Herzegovina risks breaking up.

- The EU is preoccupied with internal matters and there is little momentum behind enlargement. Many EU states are worried about the risk of the Western Balkan countries disrupting the EU’s functioning if they become members. At the same time, reforms in the Western Balkans have faltered, in part because EU membership seems increasingly remote.

- The stalling of enlargement has undermined European foreign policy in the region. Pro-European reformist political parties have been weakened, nationalist forces have grown stronger and regional and internal reconciliation after the wars of the 1990s has been undermined. The lack of a credible prospect of EU membership has also contributed to democratic backsliding and allowed Russia and China to gain influence.

- The EU is unlikely to admit new members so long as there is substantial scepticism about enlargement amongst member-states. But the Union should not give up on enlargement, as it remains its most powerful tool to foster regional reconciliation, dampen revanchist nationalism, promote better governance and reduce Russian and Chinese influence.

- The EU should push ahead with plans to integrate candidate countries more closely in the single market prior to accession, to provide achievable medium-term goals. But first the EU will need to regain its credibility and influence in the region, living up to its promises to open accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia and to grant Kosovo visa-free travel.

- Europeans should redouble their efforts to tackle corruption, state capture and democratic backsliding in the Western Balkans. Member-states have some concerns that doing so could undermine the candidates’ Western orientation. But the more the rule of law weakens, the more the EU’s attractiveness to the Western Balkans will wane relative to that of China and Russia.

- Above all, EU members must be more assertive in their efforts to tackle security challenges in the region, working together with the UK and the US. They should act resolutely to make the fragmentation of Bosnia impossible and try to push forward efforts to end the dispute between Serbia and Kosovo.

The countries of the Western Balkans are the EU’s closest neighbours, surrounded on all sides by member-states. In 2003, European leaders offered EU membership to Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, hoping that this would strengthen democracy and the rule of law. They also hoped it would stabilise the region, with the prospect of EU membership encouraging Western Balkan governments to solve bilateral disputes that had endured since the violent break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. That optimism has now disappeared. The countries in the Western Balkans are still far from EU membership, and there has only been limited progress in solving regional disputes. Bosnia is at risk of breaking up and there are renewed tensions between Serbia and Kosovo.

The EU says it is committed to enlargement, but many member-states have become sceptical. At a summit on the Western Balkans held in October 2021, EU leaders disagreed over whether to refer to enlargement in their final declaration. While they did mention it, they mostly preferred to talk of a vague ‘European perspective’ for the region. Montenegro and Serbia’s accession talks have made little headway since they began in 2012 and 2014 respectively. In October 2019, France blocked the opening of accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia, even though the two countries had carried out all the reforms that the EU had asked them to. Paris argued that that the rule of law had to be firmly entrenched in candidate countries before accession. Then, in March 2020, European leaders agreed to open negotiations with the two countries, but Bulgaria is now blocking the formal start of talks over a dispute concerning North Macedonia’s history and the origins of its language. Bosnia, for its part, is still far from meeting the criteria to start talks due to its political dysfunction. And Kosovo’s path to membership remains barred by the fact that Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Spain have not recognised its sovereignty after it unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in 2008.

The countries in the Western Balkans and their citizens have become increasingly disillusioned with the EU, and sceptical that membership is a realistic prospect. The stalling of enlargement has contributed to slowing reforms and to democratic backsliding in much of the region. The loss of a realistic prospect of EU membership has also strengthened the influence of external actors, particularly Russia and China, and encouraged many politicians in the region to turn to nationalist rhetoric, fuelling tensions between and within countries. The situation is most dangerous in Bosnia, which risks fragmenting, but there is also the possibility of other disputes flaring up, like that between Serbia and Kosovo over the latter’s sovereignty.

The state of the Western Balkans

The EU’s policy towards the Western Balkans has aimed to stabilise the region, bring it economically and politically closer to the Union, and foster regional co-operation. The EU has signed stabilisation and association agreements with all the countries in the region. These focus on liberalising trade in goods and, to a lesser degree, facilitating investment. The Western Balkans countries are at different stages of the accession process, and their prospects for membership vary significantly. This section provides an overview of the EU’s relationship with each of the six countries in the Western Balkans.

Montenegro and Serbia

Montenegro and Serbia are both negotiating membership and are the frontrunners amongst the Western Balkans countries. Montenegro, a NATO member since 2017, applied for EU membership in 2008, and started accession talks in 2012. However, negotiations have lost momentum and cannot progress further until Montenegro meets EU benchmarks on the rule of law, improving its record on issues such as freedom of expression, media freedom and corruption. According to the latest EU accession report, Montenegro has made little progress in tackling these issues: implementation of judicial reforms is “stagnating”, corruption “remains prevalent in many areas” and its civil service remains politicised. In the 2020 election, the Democratic Party of Socialists fell from power, after having ruled the country since 1990 and steered it towards Western integration. The new government relies on the support of several pro-Russian parties, but this has not so far affected Montenegro’s Western orientation and the country has continued to align with 100 per cent of EU foreign policy, including copying all EU sanctions.1

Serbia applied for EU membership in 2009 and began accession negotiations in 2014. Negotiations have not made much progress, however. The Serbian government has become steadily more authoritarian in recent years, with the country now ranked as a ‘transitional or hybrid regime’ in the Freedom House 2021 index, indicating “substantial challenges to the protection of political rights and civil liberties”.2 The European Commission’s latest report highlights a range of problems that have impeded negotiations, including lack of independence of the justice system and the civil service, corruption, the faltering fight against organised crime, and intimidation and violence towards journalists.3 Negotiations will not make much progress until Serbia’s record on these issues improves. Moreover, negotiations cannot conclude until Serbia resolves its dispute with Kosovo.

Serbia’s foreign policy is built on forging closer relations with the EU and the US, but also with Russia and China.

The EU has tried to help Serbia and Kosovo normalise their relations. In 2013 the Union helped broker an agreement between the two: Serbia agreed to dismantle the administrative structures though which it had continued to control Serb-majority areas in Kosovo, in exchange for Kosovo granting Serb municipalities greater autonomy. However, these provisions have only partly been implemented: Serbia still exerts a large degree of control over Serb areas in northern Kosovo, while Kosovo has not given more autonomy to Kosovo Serbs, fearing that this would undermine its sovereignty. Other agreements, for example over mutual recognition of number plates or property records, are also not fully implemented. In 2018, this deadlock led to the idea of a land swap agreement between Serbia and Kosovo (discussed in more detail later), but this has now been set aside. Overall, the two sides remain far apart.

The EU’s mediation efforts have been weakened by member-states’ disagreement on whether the aim of the dialogue should be to have Serbia recognise Kosovo. Major tensions between Serbia and Kosovo persist: in October a dispute over vehicle number plates escalated after Kosovo said that all vehicles entering from Serbia with Serbian plates would have to change them for Kosovo ones. This led to Kosovo Serbs blockading border crossings, followed by Kosovo deploying police units and Serbia responding with military manoeuvres on the border.

Serbia’s foreign policy is built on forging closer relations with the EU and the US, but also with Russia and China – in part because the latter pair do not recognise Kosovo’s independence. Belgrade says it is committed to seeking membership of the EU. But Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić has often sharply criticised the Union, especially during the coronavirus crisis, when he blamed the EU for lack of solidarity. And although Serbia is the leading Western Balkans contributor to EU military operations, its degree of alignment with EU foreign policy positions was only 56 per cent in 2020. Specifically, Serbia has not signed up to the EU’s sanctions against Russia or Belarus, or to its statements criticising China’s actions towards Hong Kong.

Albania and North Macedonia

Albania and North Macedonia hope to begin accession negotiations soon. Albania applied for membership in 2009, the same year in which it became a NATO member. It became an official candidate for EU membership in 2014, and the European Commission recommended opening accession talks in 2018. In March 2020 EU states agreed to start talks, but this has not happened yet. Member-states insist that talks with Albania and North Macedonia should be opened at the same time to avoid friction between them, and Bulgaria is blocking the start of talks with North Macedonia. According to the Commission, Albania still struggles with issues such as widespread corruption, limits to freedom of expression, and political pressure, threats and violence towards journalists.4 Moreover, the April 2021 elections were marred by allegations of vote-buying by political parties.5 If negotiations started, they would probably face hurdles like those already experienced by Serbia and Montenegro.

North Macedonia, a NATO member since 2020, applied for membership in 2004, and became an official membership candidate in 2005. According to the European Commission, North Macedonia has met the conditions to open accession negotiations since 2009. But for many years Greece blocked the start of talks over the issue of the country’s name. In 2019, the Prespa agreement ended the dispute, with what was then the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia changing its name to North Macedonia. Despite this, the start of talks is now blocked by Bulgaria. Sofia argues that North Macedonia does not have a separate ethnic identity or language from its own, and wants North Macedonia to recognise that its language and identity have Bulgarian roots. The failure to start negotiations talks weakened North Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev and paved the way for the return to power of the nationalist opposition, which opposed the name deal with Greece and is ambiguous about EU membership. If negotiations start, North Macedonia will still need to make progress in addressing issues related to the rule of law, including tackling corruption and lack of transparency in civil service appointments.6

Bosnia and Kosovo

Both Bosnia and Kosovo remain far from being able to start membership talks. Bosnia applied for EU membership in 2016, but it remains deeply dysfunctional. The 1995 Dayton peace agreement ended the Bosnian civil war, setting up a state consisting of a Bosnian Serb entity and another made up of Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks). However, Dayton was a shaky compromise and de facto empowered ethnic nationalist leaders. Bosnian Croat nationalists have been pushing to obtain more powers and Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik has been threatening secession. Dodik has clashed with the High Representative for Bosnia, an international figure tasked with upholding the Dayton agreement and with broad powers to do so. In July 2021, the then High Representative, Valentin Inzko, passed a law imposing penalties for genocide denial. Dodik responded by boycotting state institutions, threatening to set up separate administrative bodies and to revive a Bosnian-Serb army – moves that would amount to secession and could spark violence. Christian Schmidt, the current High Representative, has warned that the country faces “the greatest existential threat of the post-[Bosnian]war period”. Dodik has support from Russia and Serbia. Even if he does not follow through with his threats fully, his actions are weakening Bosnia’s central government and the High Representative’s authority.

Kosovo, which formally declared independence from Serbia in 2008, cannot apply for membership of the European Union, because Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Spain do not recognise its sovereignty. They are concerned that this could fuel secessionist movements on their own territory, or (in the case of Greece and Cyprus) because it would legitimise the northern Cypriot entity set up after Turkey’s 1974 invasion of the island. Nevertheless, Kosovo has had a stabilisation and association agreement with the EU since 2016. Kosovo is also negotiating visa-free travel with the EU. In 2018, the Commission said that the country had met all technical criteria, but member-states have not agreed to the measure yet, with many sceptical of the country’s rule of law record. In practice, whether Kosovo can become a candidate for membership depends on whether it can normalise its relations with Serbia. This would pave the way for Kosovo’s recognition by the remaining five EU member-states, and ultimately for membership.

Why enlargement faltered

The stalling of enlargement is due to two interconnected and mutually reinforcing factors: enlargement fatigue on the side of the EU, and loss of momentum on the side of the Western Balkans countries.

Enlargement sceptics are worried that admitting countries with a weak rule of law record could lead to issues.

Enlargement fatigue

Admitting new members to the EU requires unanimity between member-states, but many do not currently want to enlarge the Union to the Western Balkans. Enlargement in the Western Balkans is perceived as bringing few benefits and having many risks. The leading sceptics are France, Denmark and the Netherlands, although many other member-states share their concerns to some degree. Enlargement sceptics are worried that admitting countries with a weak rule of law record could lead to issues after they become members. The risk of backsliding appears even starker after the rule of law issues that have emerged in Poland and Hungary, and the difficulties that the EU has had in tackling them. Even the ‘co-operation and verification mechanisms’ that the EU established to ensure that Bulgaria and Romania continued to tackle persistent rule of law shortcomings after joining the EU have had limited success. The risk of a country violating the rule of law after becoming an EU member has convinced many EU states that democratic institutions and checks and balances need to be firmly entrenched in candidate countries.

For many member-states, the EU’s current focus needs to be on internal consolidation. EU citizens are not enthusiastic about enlargement, with the latest Eurobarometer survey suggesting that only a narrow majority of those who gave their opinion favour allowing more countries to join.7 Enlargement has also lost momentum because the EU has been preoccupied with a range of internal issues, ranging from migration to the coronavirus pandemic. The UK’s departure from the Union has further reduced momentum for enlargement, as London was one of the policy’s main advocates. Finally, widespread anti-immigration sentiment in the EU, driven by the influence of right-wing anti-immigration parties in many member-states, has made many leaders more reluctant to admit countries that are much poorer than the EU and that, in some cases, have substantial Muslim populations. Anti-immigration parties can shape the political agenda even if they are not in government: French President Emmanuel Macron’s concern about their popularity has pushed him to take a tough stance on migration issues and on enlargement.

As long as European governments and citizens oppose admitting new members from the Western Balkans, the EU is unlikely to open talks with Albania and North Macedonia, still less to admit new members. It also seems unlikely that the EU will admit new members until it has made substantial progress in addressing its rule of law crisis with Poland and Hungary. Sceptical member-states would probably have to be satisfied that the EU has the right tools to deal with democratic backsliding in a member-state before they dropped opposition to further enlargement.

Even if the EU’s ability to deal with its own rule of law issues was no longer a concern, however, bilateral disagreements might pose a barrier to the Union admitting new members. Several EU states have bilateral issues with Western Balkans countries that they could raise during the accession process: Greece over North Macedonia and over the status of the Greek minority in Albania; Bulgaria over North Macedonia’s heritage; and Croatia with Bosnia over the status of the Croatian minority there and over its borders with Bosnia, Montenegro and Serbia. Finally, any treaty marking accession to the EU would have to be ratified by all EU states. Some may choose to hold referenda before ratification, which would be occasions for populist parties to lead anti-enlargement campaigns. The road to enlargement will remain rocky.

Accession fatigue

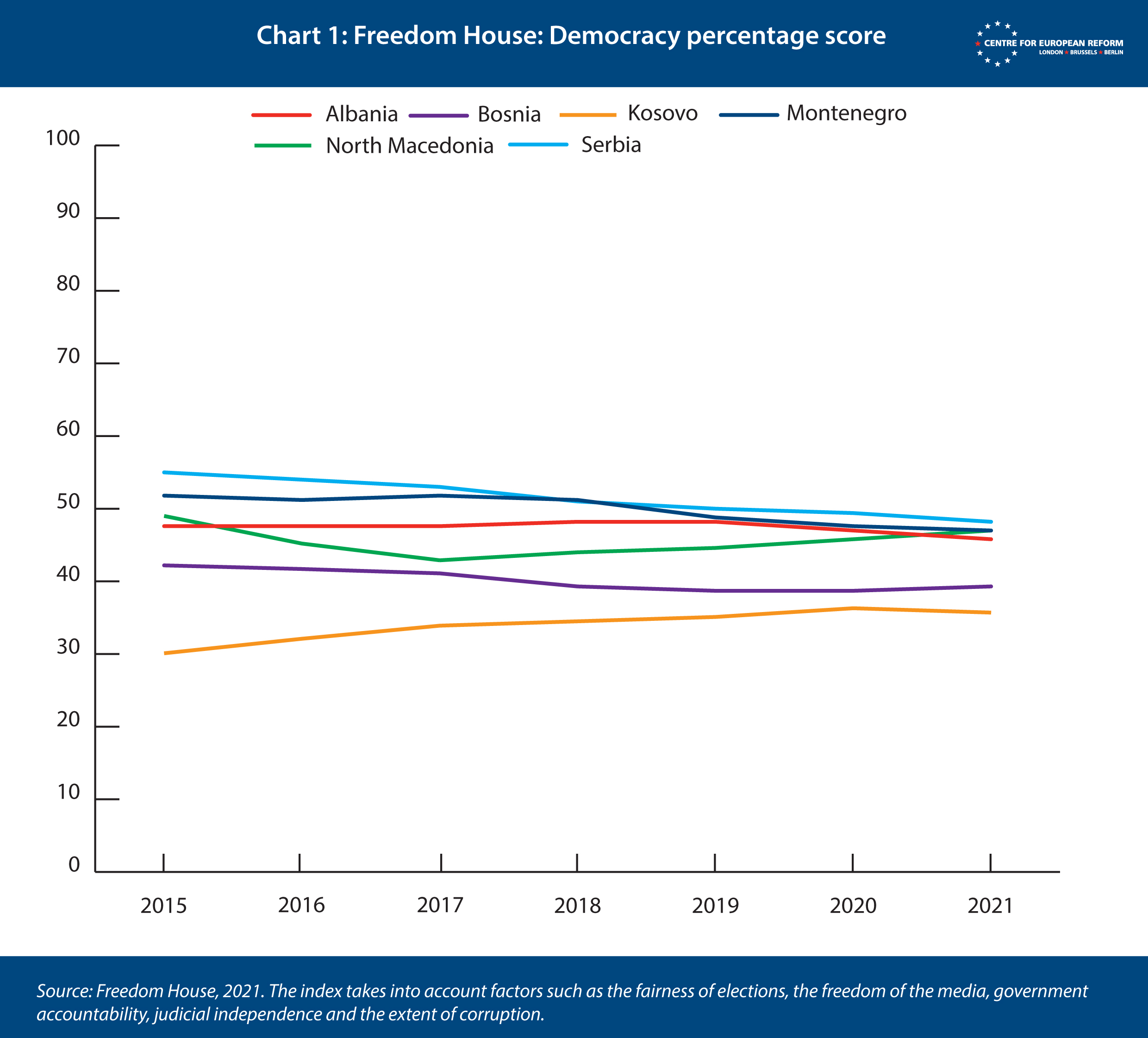

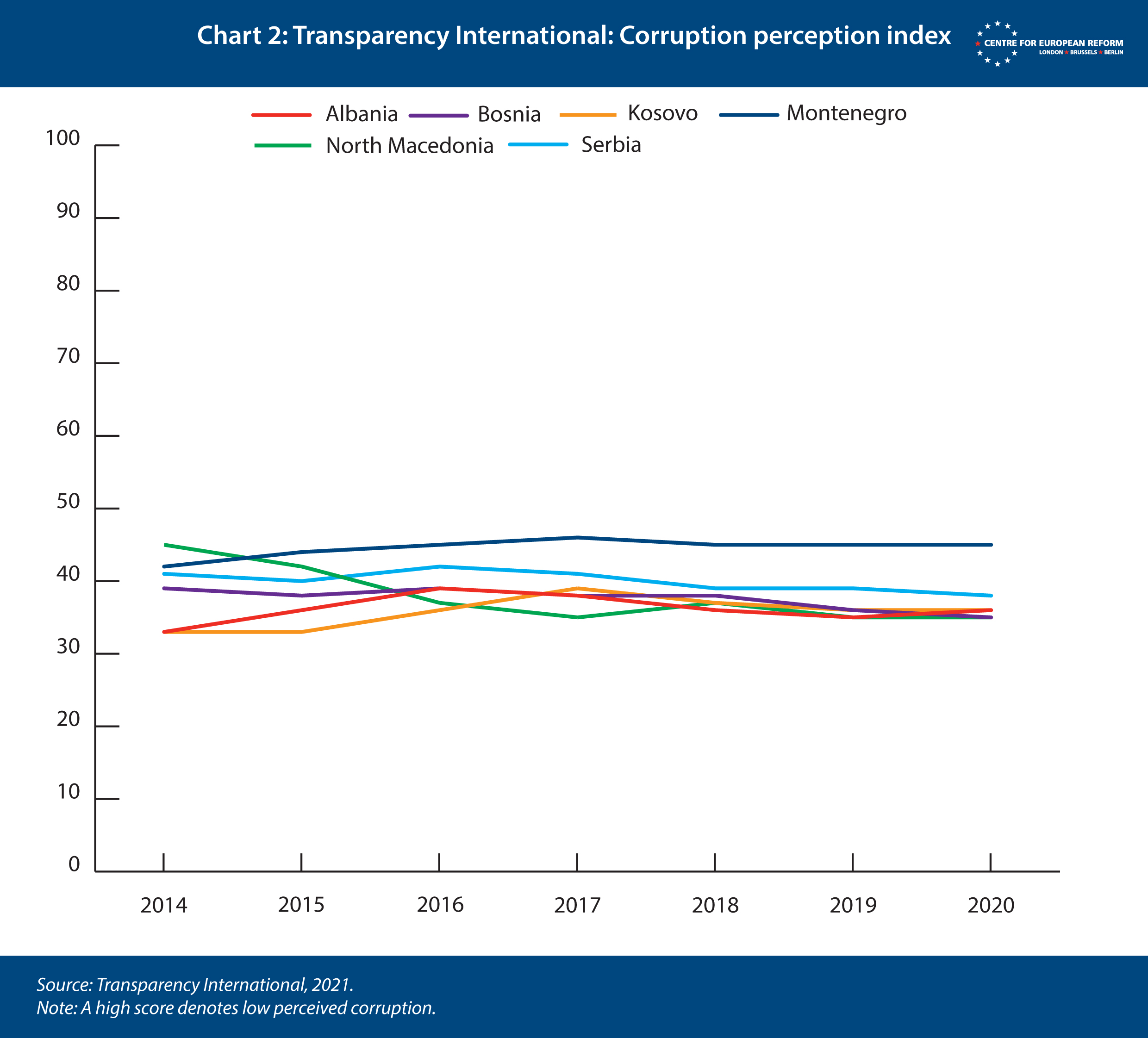

While the EU has become sceptical of admitting new members, the Western Balkans candidates are also responsible for the current stasis. The Commission’s latest report on the region highlights a range of issues, including widespread corruption, “risks of undue pressure on the judiciary”, intimidation and violence towards journalists, lack of a fully free media landscape, and boycotts of elections and parliamentary proceedings by political parties.8 NGOs are even bleaker than the Commission in their assessments. Freedom House ranks all six Western Balkans countries as ‘transitional or hybrid regimes’, with all of them aside from Kosovo on a downwards trajectory in the past few years (Chart 1).9 According to Transparency International, all six countries in the region suffer from ‘state capture’ – the exploitation of government for private interests, enabled by extensive corruption (see Chart 2) and the lack of an effective independent judiciary.10

One reason why the Western Balkan states have been slow to reform is that EU accession is not necessarily in the interest of many Western Balkan leaders. Leaders whose power depends on being able to give out political favours and government contracts have few incentives to reform. Cracking down on corruption and increasing transparency in areas such as public procurement would probably mean losing power, and possibly also facing prosecution for past misdeeds. At the same time, control over the media means that electoral contests are unlikely to be fair, which makes it harder for reformist governments willing to pursue EU accession vigorously to be elected in the first place.

The limited progress in implementing reforms in the region is also partly due to the EU’s own actions. The lack of a realistic prospect of membership and the EU’s failure to abide by its promises have reduced incentives for reform. The EU has also indirectly contributed to the erosion of the rule of law in the Western Balkans. It has legitimised authoritarian leaders by treating them as partners and provided them with funding linked to the accession process, which helped them consolidate their influence.11 EU leaders and institutions have often been unwilling to criticise authoritarian leaders like Serbia’s Vučić for undermining checks and balances, concerned that this would damage bilateral relations.

Even though they cannot sense any tangible progress towards the goal, big majorities of citizens of the Western Balkan countries still want EU membership. According to a survey by the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group, in Albania 94 per cent favour membership, in Bosnia 83 per cent, in Kosovo 90 per cent, in Montenegro 83 per cent and in North Macedonia 79 per cent. The exception is Serbia, where only 53 per cent want to join the EU.12 Other polls suggest that only a third of Serbians think that EU membership would be positive.13

The EU’s new approach

With membership negotiations stuck, the EU has focused on an incremental approach. In 2020, the Commission made some changes to the accession process in response to concerns raised by France and other EU members. Negotiations are meant to be more tightly linked to candidate countries’ progress in observing the rule of law, and to be more easily reversible. And candidate countries are supposed to be able to benefit economically before accession, through gradual integration in the single market once they have completed negotiations in a specific policy area. The Commission says integration could be achieved, for example, by granting an adequacy decision on data protection standards once a country has fully adopted EU rules in that area. And, under the EU’s current budget, the EU’s funding for the region is not pre-allocated to individual countries, giving the Commission more flexibility to direct money towards countries that are more advanced in implementing reforms.

Europe has also tried to foster regional economic integration.

At the same time, the EU is trying to foster economic development and regional integration. The Union has provided €3.3 billion for the Western Balkans to help address the health and socio-economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic. And in late 2020, the EU launched an ‘economic and investment plan’ worth €9 billion in grants, which the Commission says can be used to leverage an additional €20 billion in private investment. The funds are designed to help improve infrastructure, foster green energy development and promote digitisation of the Western Balkans’ economies.14 Europe has also tried to foster regional economic integration. The Berlin process, a German-led initiative launched in 2014, is meant to lead to a regional market to facilitate the free flow of people, goods, services and capital. In November 2020, leaders from the six Western Balkans states agreed to set up a common regional market along the lines envisaged by the Berlin process. The EU has also been positive about the Serbian-led Open Balkan initiative, which currently involves Albania and North Macedonia and aims to reduce border checks. However, it is unclear how the initiative relates to the common regional market, and Bosnia, Kosovo and Montenegro see it as a Serbian-dominated scheme.

EU assistance will help stabilise the Western Balkans’ economies. And in the long run, regional economic integration would be economically beneficial to Balkan countries. But the economic gains of regional integration are very small compared to those of integrating with the EU market. Politically too, regional economic integration is a poor substitute for accession as it does not provide many incentives to drive reforms and resolve disputes. And countries in the Western Balkans are likely to be sceptical of the EU’s willingness to follow through with its pledges of gradual integration in the single market, both because of the EU’s past failure to live up to its promises and because the revised accession process remains untested.

The risks of stasis

The stalling of enlargement, combined with the lack of a robust European policy towards the Western Balkans, is harming the EU’s interests in the region. As enlargement has faltered, so the idea of border changes between Balkan countries has gained traction. In 2018 and 2019 Serbia and Kosovo discussed land swaps, with support from the Trump administration. The EU institutions were open to the idea if it allowed Kosovo and Serbia to normalise their relations. But some member-states, particularly Germany, thought that land swaps would be dangerous because they could give momentum to the idea of partitioning Bosnia and North Macedonia along ethnic lines. The idea of land swaps met political opposition in Kosovo, and the country’s president, Hashim Thaçi, resigned in November 2020 after being indicted for war crimes. But talk of moving borders re-surfaced in a more dangerous form in April 2021, with an informal paper, allegedly authored by Slovenia’s Prime Minister Janez Janša, calling for extensive border changes in the Balkans, including the partition of Bosnia and Kosovo, with the two countries’ territories being divided between their neighbours. Redrawing borders along ethnic lines would be risky, because there would be large minorities left behind, even under extensive border alterations. For example, many Kosovo Serbs do not live along the border with Serbia, and a Bosnian Serb entity would have a substantial Bosniak minority. Opponents of border changes could take revenge on minorities on the wrong side of the border.

The prospect of accession steered countries away from nationalism, helped bring about the Prespa agreement between Macedonia and Greece, and fostered dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo. Now that accession has stalled, these achievements are at risk. Pro-European reformist forces across the region have been weakened, while authoritarian political forces that appeal to nationalism have grown stronger. In North Macedonia the progress of recent years could be erased if the nationalist opposition returns to power and refuses to fully implement, or rejects, the Prespa agreement. The region is already seeing a revival of dangerous rhetoric, including calls for border changes and glorification of war criminals. In July 2021 Serbian interior minister Aleksandar Vulin talked of creating a “Serbian world” and uniting Serbs “wherever they live”. Serbian revanchism will lead to more tension between Serbia and Bosnia, Montenegro and Kosovo; and to greater tensions within those countries. In 2017, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama said that a union between Albania and Kosovo would be a possibility if EU membership proved unreachable – a statement amplified by many politicians in Kosovo who want close ties with Albania. Renewed discussions on uniting Albania and Kosovo could lead to friction between Albania and Serbia, and between Albania and North Macedonia over the latter’s Albanian minority.

Moscow has carefully cultivated support in the region, supporting nationalist groups and using misinformation to undermine the West.

The biggest risk in the Balkans, however, is violence in Bosnia. Further moves towards secession by Dodik would threaten to undo the Dayton settlement. The substantial Muslim minority in the territory of a breakaway Serbian entity would fear for its safety, Croat nationalists would probably agitate to unite with Croatia, and Bosnian Muslims would fear being left in an unviable rump state. It is possible that Russia might deepen its involvement, sending proxies to bolster a breakaway Serb entity. And, if there is violence, Turkey may intervene to protect Bosnia’s Muslims. An EU mission is supposed to keep the peace, but the number of peacekeepers in the country has been reduced to around 600 troops spread across different areas – too few to pose an effective deterrent or respond to violence. Europe could see large number of refugees.

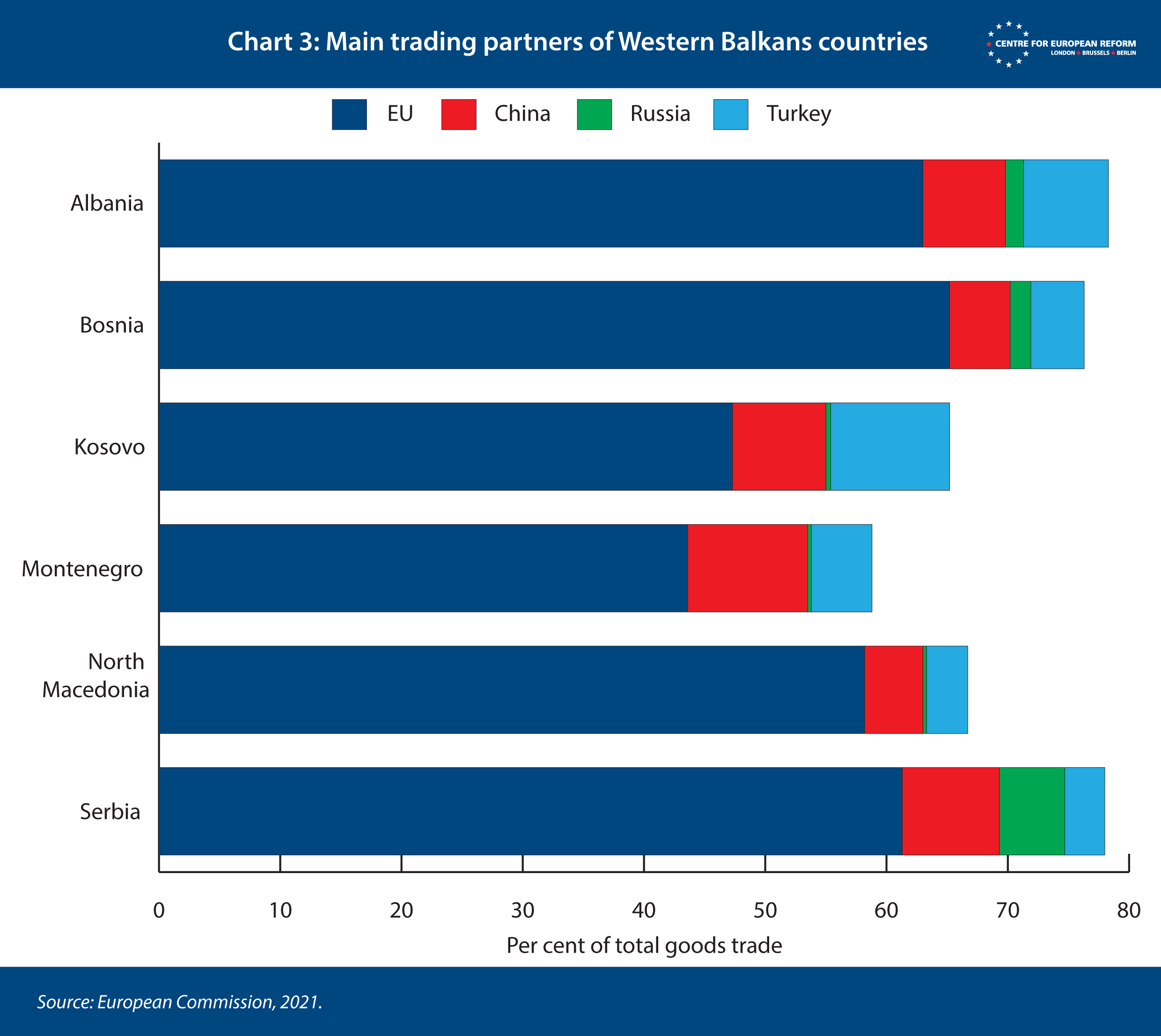

The stalling of the accession process is fuelling anti-Western attitudes and leaving the door open for growing influence by non-Western actors, particularly Russia and China. In economic terms the EU is the leading trading partner for all countries in the region (Chart 3) and EU investments make up over 60 per cent of foreign direct investment in the region.15 However, the EU’s economic influence and financial assistance do not translate into popularity amongst many citizens in the Western Balkans. According to a recent survey, only Montenegrins see the EU in more positive terms than other external powers (including the US). In all Western Balkan countries aside from Albania, the EU is seen as a bigger spreader of disinformation than Russia. Serbian citizens are the most sceptical of the EU. They think that China provides greater financial assistance than the Union, and fewer than 20 per cent see the EU’s influence as positive, as opposed to 60 per cent for Russia and 55 per cent for China.16

Russian influence is a challenge for Europeans in several ways. Moscow wants to prevent countries that are not yet members of NATO and/or the EU from joining these institutions, to increase its influence and to enhance its status as a global power.17 Undermining the prospect of EU accession for countries in the Western Balkans also appeals to Moscow because it shows countries like Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine that obtaining EU membership is impossible, and therefore undermines pro-Western forces there.

Russian economic involvement, particularly in the energy sector, gives Moscow leverage. According to Eurostat, Bosnia, North Macedonia and Serbia get virtually all their gas from Russia, and Gazprom holds a majority stake in Serbia’s largest oil and gas company. The shady nature of Russia’s economic dealings contributes to fostering corruption, making accession-related reforms more difficult. Moscow has carefully cultivated support in the region, supporting nationalist groups and using misinformation to undermine the West, often appealing to a common Orthodox Christian, pan-Slavic identity. Russia hopes to use the resultant pro-Russian sentiments in NATO members North Macedonia and Montenegro to weaken the alliance’s cohesion. In 2016, Russia was allegedly involved in a coup attempt in Montenegro, aimed at installing pro-Russian forces in power and preventing the country from joining NATO.

Russian actions also fuel ethnic or bilateral disputes between and within countries. Moscow has given strong support to Serbia over its stance towards Kosovo, making resolution of the dispute more difficult. In Bosnia, Moscow has backed Dodik’s attempts to undermine Dayton, helped to train his paramilitary forces, and tried to undermine the office of the High Representative in Bosnia. In North Macedonia, Russia has tried to stoke opposition to the country’s name change and nourished fears that Albania and Bulgaria wanted to partition North Macedonia between them. The EU does not want to import conflicts within or between acceding states, so instability ensures that the Union keeps Western Balkans countries at arm’s length.

The lack of a concrete prospect of becoming EU members, combined with the need for new investment in the aftermath of COVID-19, is also likely to boost China’s influence. Beijing sees both economic opportunities in the region and the chance to gain allies to support its policies on issues like Xinjiang, Hong Kong and the South China Sea. China has signed Belt and Road agreements with all Western Balkan countries apart from Kosovo, and has poured substantial investment into the region, particularly in Serbia. China’s investments have focused on infrastructure, especially highways, and on the energy sector. Beijing has also provided assistance during the pandemic and sought to foster the perception that it showed more solidarity than the EU, gaining praise from Serbia.

China’s influence is not as damaging to European interests as Russia’s. Beijing does not aim to block NATO or EU expansion in the region and it has no interest in fostering instability and stoking tensions. Nevertheless, China’s growing economic influence in the Balkans is also detrimental for European interests there. No-strings-attached Chinese investments have a corrosive effect: they weaken the rule of law, fuel corruption and discourage countries in the Western Balkans from adopting EU rules on labour and environmental standards. Chinese lending can trap countries under big piles of debt, as illustrated by Beijing giving Montenegro a $1 billion loan to build a highway – which the country is struggling to pay back.18 In security terms too, China’s role is not fully aligned with the EU’s interests. Beijing has supported Russia’s efforts to abolish the post of High Representative in Bosnia and to de-legitimise the current incumbent, Christian Schmidt. Beijing’s stance has therefore indirectly emboldened Dodik to be more assertive.

Aside from China and Russia, Turkey’s influence has also grown. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Ankara has focused on expanding cultural and educational links in the region, for example by financing the reconstruction of mosques and historical buildings and by setting up branches of its cultural institute. Turkey’s soft power is strongest among Muslim populations, but Ankara has also tried to build close relations with Bosnian Serbs and with Serbia. Some EU states, particularly France, think that Turkey’s influence in the Western Balkans poses a threat. But unlike Russia, Turkey does not aim to stop the Western Balkans’ closer integration into the EU and NATO. Instead, Ankara supports the region’s further integration into the two institutions, thinking that this would allow it to gain more friends in both. Turkey has also pushed for more countries to recognise Kosovo as sovereign, a policy that is aligned with that of most EU states and the US.

Finally, Europe’s influence in the Western Balkans is also undermined by Serbia’s rise as an important regional actor in its own right. Serb populations in Bosnia, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Kosovo mean that Serbia is influential beyond its own borders. Belgrade has also sought to increase its influence through the Open Balkan initiative and by providing well-timed assistance to its neighbours during the pandemic. Serbia’s balancing act between the West, Russia and China could come to be seen as a model for other countries in the region to follow – to the EU’s detriment.

Towards a new European strategy

Europeans need a more assertive policy in the Western Balkans to prevent Bosnia’s disintegration and possible return to violence, continue to promote regional reconciliation, and counter Russian and Chinese influence. Enlargement will take time and will require the EU to develop effective tools to deal with democratic backsliding in current and future member-states. But Europeans should not give up on enlargement. Doing so would only reduce their influence, further sap momentum for reform and consolidate the drift towards authoritarian politics in the Western Balkans.

Enlargement remains Europe’s most powerful tool.

Enlargement remains Europe’s most powerful tool for fostering regional reconciliation, dampening nationalism, promoting better governance and reducing Russia’s and China’s influence. Europe should push forward with plans to provide candidates for membership with appealing incentives during the accession processes, to serve as achievable medium-range goals that can spur reforms. At the same time, Europe needs to be more assertive in fighting corruption and democratic decay.

More tangible benefits

The EU’s plans to provide candidate countries with concrete benefits prior to accession look like a second-best option compared to membership, but they could still help the Union restore its influence in the region and revitalise reforms. However, the EU’s incentives need to be more concrete and substantial to be credible. They need to be effective in promoting positive change, regardless of whether some member-states choose to delay enlargement. The EU’s proposals for greater access to the single market prior to accession are unclear and poorly understood by candidate countries. The EU should spell out how its ideas will function in practice in different policy areas, and clearly communicate their tangible benefits for citizens and businesses in accession countries.

Economic benefits can only be part of the puzzle, however. The EU should offer candidate countries tangibly closer political ties as they progress towards membership and become gradually more integrated into the EU. Candidates that are advanced in implementing the acquis should be politically associated to the EU as closely as possible. Leaders from accession countries could be invited more regularly to attend meetings of European leaders. In policy areas in which candidate countries have completed negotiations, their ministers should be invited to informal meetings of their EU counterparts. Like EEA/EFTA states, advanced accession candidates could also second civil servants to the Commission, hold political dialogues with EU Council working parties, and participate in Commission expert groups and in comitology – the procedure through which EU legislation is implemented. These steps would be reversible in case of rule of law backsliding.

Greater economic and political incentives are unlikely to appeal to corrupt elites. But they would appeal to reformist pro-European leaders in the Western Balkans and provide them with better arguments to use in political campaigns. Economic integration would bring tangible benefits to citizens in the Western Balkans, while political integration would make them feel closer to the EU. And as countries reformed, they would come closer to meeting the criteria for membership, meaning that member-states would become less sceptical about letting them join.

Any EU offers of closer economic and political ties before accession are unlikely to be seen as genuine unless the EU first re-establishes its credibility in the region. To do so, member-states must live up to their promises, opening accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania and granting visa-free travel to Kosovo.

Greater focus on the rule of law

Europeans should be much more proactive in their efforts to counter corruption, state capture and democratic backsliding in the Western Balkans. Member-states are often concerned that being tougher on these issues could undermine accession candidates’ European and Western orientation, and potentially allow other powers to gain influence. But these fears are misplaced. If the EU provides increased funding and benefits without making them conditional on good governance, the Union only risks facilitating corruption and strengthening authoritarianism. Authoritarian leaders unchecked by an effective opposition and an independent media are more likely to turn to nationalist rhetoric, fuelling tensions in the region. And if European leaders and EU institutions do not call out democratic backsliding when it occurs, they tarnish their own credibility, and allow local politicians to distract citizens from their own failings and point to the Union as a scapegoat when accession negotiations falter.

EU leaders, together with the UK and the US, should show they will not allow conflict to break out in Bosnia.

Europe should start by doing more to regularly acknowledge that democratic backsliding is an issue in much of the Western Balkans, and push countries to address it. The Commission’s accession reports should be less technical: they should clearly label cosmetic reforms and democratic backsliding as such and focus more on assessing the implementation and enforcement of reforms. Member-states should be more willing to highlight negative developments, to show that they are not only an issue for the Commission. This would enhance the EU’s overall credibility. Europeans should carefully monitor the way their funding is allocated so that it does not foster corruption, and they should reduce funding to countries that violate the rule of law, re-orienting money towards civil society organisations. Finally, the EU should hold accession candidates to account on media freedom, making it a central consideration in deciding whether to grant funds, and providing more financing to independent media than the €20 million it provided between 2014 and 2020.19

A more assertive foreign policy

EU member-states, working with the UK and the US, need to be more determined in stabilising the region. Under Biden’s presidency, European and US policies towards the Western Balkans are aligned, whereas Trump had tried to side-line the EU.

EU leaders, together with the UK and the US, should show they will not allow conflict to break out in Bosnia. Europeans should strengthen their military presence in the country to ensure that they can deter Dodik and his backers from further secessionist moves. At the same time, Europeans should stress to Dodik that secession would result in international isolation and sanctions, and signal support to the Bosnian government and the High Representative through high-level visits and engagement. The EU, the UK and the US should condemn and be ready to sanction those who adopt extreme nationalist rhetoric, deny genocide and glorify war criminals. In the medium term, stabilising Bosnia is likely to require changes to the post-Dayton settlement to ensure that Bosnian institutions can function properly. These cannot be imposed from the outside, but Europe and the US should help Bosnians come to an agreement on what they should be, and then help them to implement the changes. To do so, they will have to engage more broadly with civil society and with political parties other than Bosnia’s three main ethnic parties.

EU member-states, the UK and the US should also continue to encourage Serbia and Kosovo to normalise their relations. There is little sign that the two are ready to make difficult compromises, as there is little sense of urgency. Europeans and the US should try to provide Kosovo and Serbia with greater incentives to negotiate. By reviving the prospect of membership, the EU would give Serbia and Kosovo more reason to fully implement their existing commitments and encourage them to make further progress towards striking an agreement. Land swaps could be part of a final agreement if the two sides want – although the West should not push the idea. If all EU member-states recognised Kosovo, this would signal that the West was united in supporting Kosovo’s independence. This would make EU mediation more effective, pave the way for Kosovo’s integration into the EU and NATO and persuade Serbia that a settlement with Kosovo is in its interest. If recognition is a step too far for some member-states, they should explore how they can increase their engagement with Kosovo.

Finally, Europeans should try to limit Russian and Chinese influence in the region. Trying to compete with China by providing funding without strings attached would be self-defeating, as it would worsen governance standards. Instead, Europeans should step up their efforts to fight state capture and to promote energy diversification, reducing Beijing and Moscow’s appeal. Europeans should also deepen security co-operation with countries in the region. The more that European states and the US co-operate with countries in the Western Balkans, the less likely it is that they will work with the West’s rivals. There is scope for closer foreign policy consultation between countries in the Western Balkans and the EU. The Union could encourage accession candidates, particularly NATO members, to take part in some of its defence co-operation projects, like that on military mobility, which is focused on easing physical and regulatory barriers to moving troops and equipment.

Conclusion

The Western Balkan countries are Europe’s closest neighbours, and the EU should be able to use its political and economic weight to promote stability, good governance and economic prosperity in the region. But the stalling of EU enlargement has contributed to a negative spiral in the Western Balkans, with rising authoritarianism, nationalist recrimination and ethnic tensions. EU member-states, working together with the UK and the US, need to rise to the challenge and reverse these negative developments before they gain further momentum. If they fail to do so, the challenges in the Western Balkans will only grow larger, and Europeans may have to deal with armed conflict on their doorstep.

2: Freedom House, ‘Nations in transit methodology’, 2021.

3: European Commission, ‘Serbia 2021 report’, October 2021.

4: European Commission, ‘Albania 2021 report’, October 2021.

5: OSCE, Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, ‘Republic of Albania parliamentary elections 25 April 2021: Limited election observation mission final report’, July 26th 2021.

6: European Commission, ‘North Macedonia 2021 report’, October 2021.

7: European Union, ‘Standard Eurobarometer’, Spring 2021.

8: European Commission, ‘2021 communication on EU enlargement policy’, October 19th 2021.

9: Freedom House, ‘Democracy score’, 2021.

10: Transparency International, ‘Examining state capture: undue influence on law-making and the judiciary in the Western Balkans and Turkey’, December 15th 2020.

11: Solveig Richter and Natasha Wunsch, ‘Money, power, glory: The linkages between EU conditionality and state capture in the Western Balkans’, Journal of European Public Policy, volume 27, issue 1, 2019.

12: Corina Stratulat, Natasha Wunsch, Srdjan Cvijić, Zoran Nechev, Matteo Bonomi, Gjergji Vurmo, Marko Kmezić with Miran Lavrič, ‘Escaping the transactional trap: The way forward for EU enlargement’, Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group, November 2nd 2021.

13: Stefani Weiss, ‘Pushing on a string? An evaluation of regional economic co-operation in the Western Balkans’, Bertelsmann Stiftung and Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, August 19th 2020.

14: European Commission, ‘An economic and investment plan for the Western Balkans’, October 6th 2020.

15: European Commission, ‘EU-Western Balkans relations’, October 2021.

16: Nikolaos Tzifakis, Milica Delević, Marko Kmezić, Zoran Nechev with contribution by Miran Lavrič and Tena Prelec, ‘Geopolitically irrelevant in its ‘inner courtyard’? The EU amidst third actors in the Western Balkans’, Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group, December 3rd 2021.

17: Dimitar Bechev, ‘Russia’s strategic interests and tools of influence in the Western Balkans’, Atlantic Council, December 20th 2019; Paul Stronski, Annie Himes, ‘Russia’s game in the Balkans’, Carnegie, February 6th 2019.

18: Sophia Besch, Ian Bond and Leonard Schuette, ‘Europe, the US and China: A love-hate triangle?’, CER policy brief, September 21st 2020.

19: European Commission, ‘EU support to media in the Western Balkans’, October 2019.

Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

December 2021

View press release

Download full publication