The Sahel: Europe's forever war?

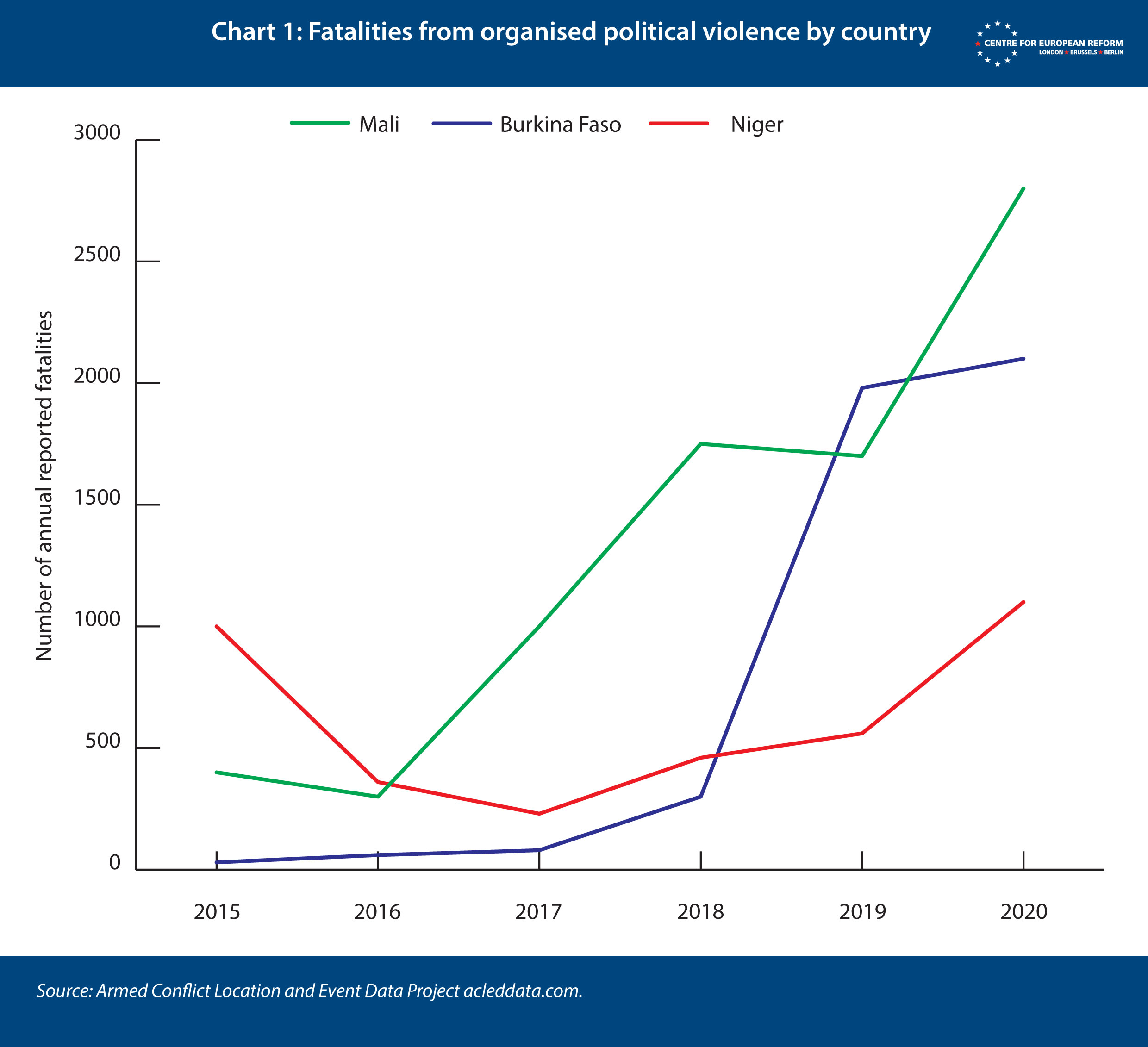

- Violence in the Sahel region of Africa has been continual for nine years. Despite the long-term involvement of the EU and France, the conflict has continued to escalate, spreading from Mali to Niger and Burkina Faso, costing thousands of civilian lives every year.

- The region is of strategic interest to Europe: a large number of migrants to the EU come from the Sahel or transit through it. It also hosts a sizeable presence of armed Islamist groups affiliated with al-Qaida and Islamic State (IS). But the Sahel also matters for Europe’s credibility as a crisis manager. Having invested money and political capital in the region, the EU must now prove that it is capable of solving complex problems in its own backyard.

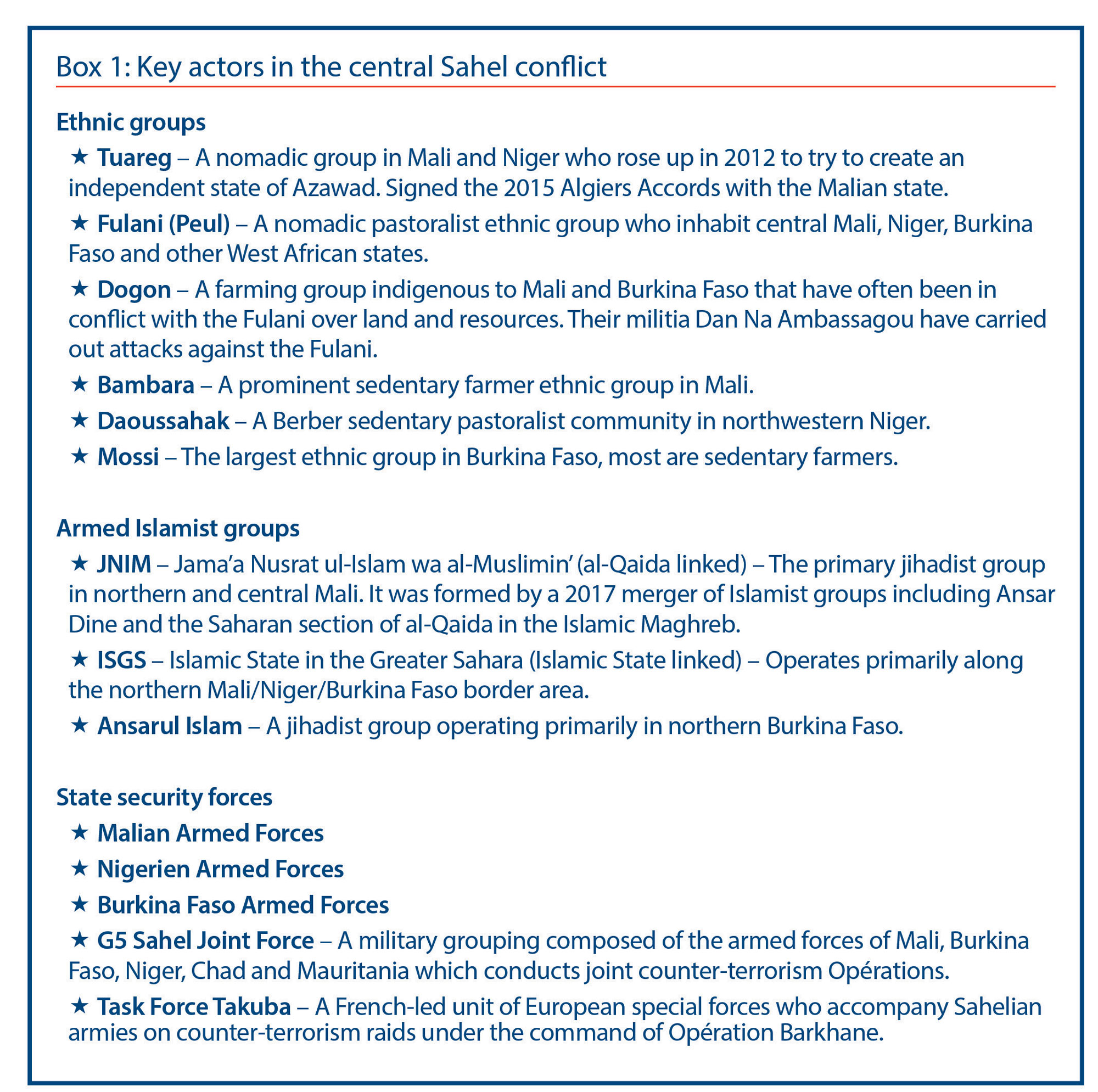

- The violence first began in northern Mali in 2012, and was instigated by Tuareg insurgents who were briefly supported by jihadist groups. Since 2015 new intercommunal conflicts have festered in central Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. Jihadist groups have taken advantage of ethnic tensions to increase their membership.

- Europe’s current military-focused approach, pioneered by France in 2013, has achieved little more than a string of tactical victories against jihadists in the past eight years.

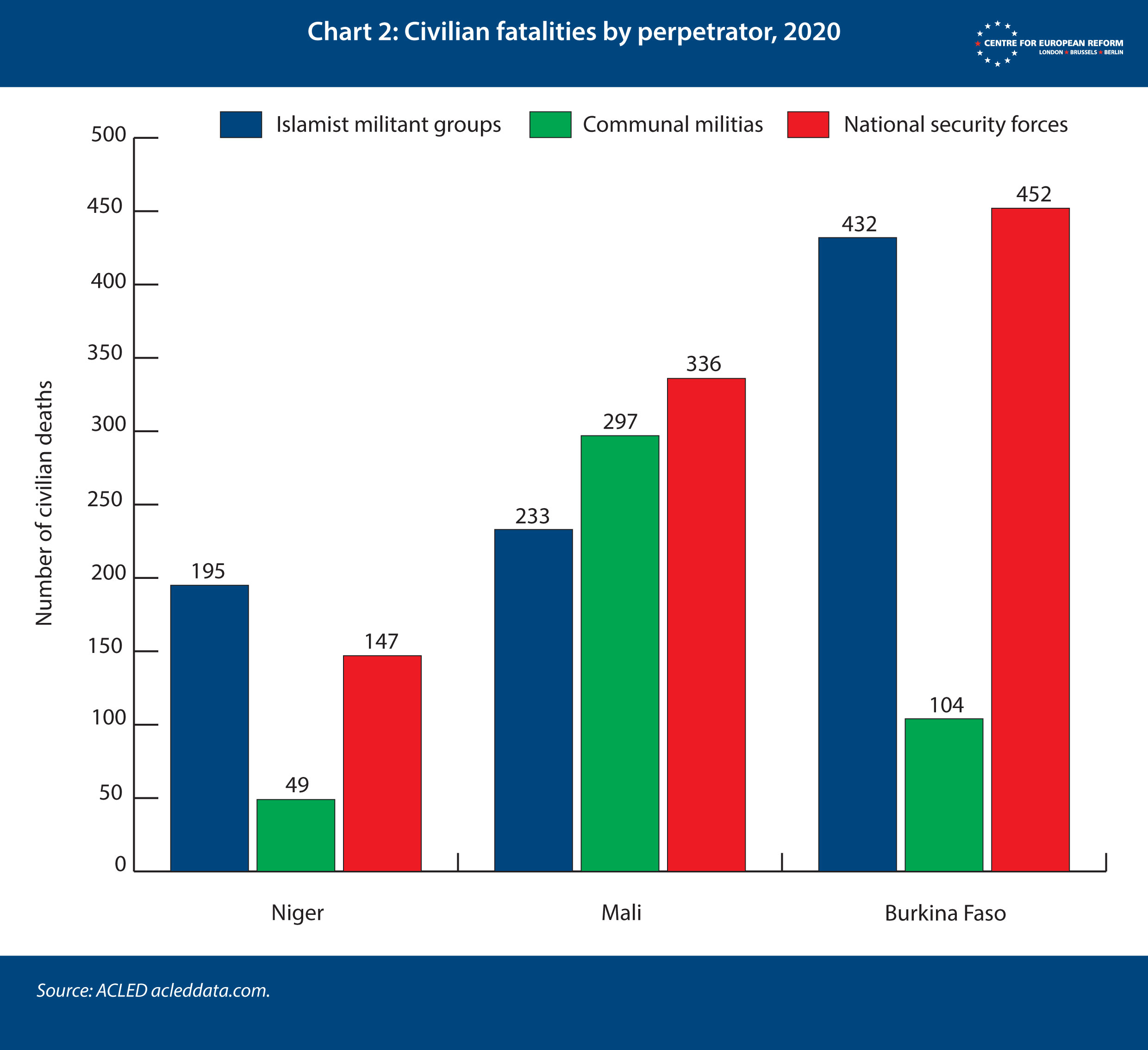

- By supporting governments that are feared and mistrusted by many of their citizens, Europe may be undermining its own aim of curbing violence. In 2020, more civilians were killed by national security forces than jihadist groups in Mali and Burkina Faso. Human rights abuse by state actors is driving recruitment to jihadist groups.

- Europe needs to supplement its military commitments by engaging more on a political level with the governments it is supporting, demanding greater transparency over spending and tougher anti-corruption measures as pre-conditions for releasing funds. As the EU reviews its Sahel strategy in 2021, Brussels has a particularly crucial role to play in facilitating this shift.

- The EU should engage more intensively with civil society to help build trust between Sahelian states and their citizens, and combat the issues of poor governance that underpin the conflcit.

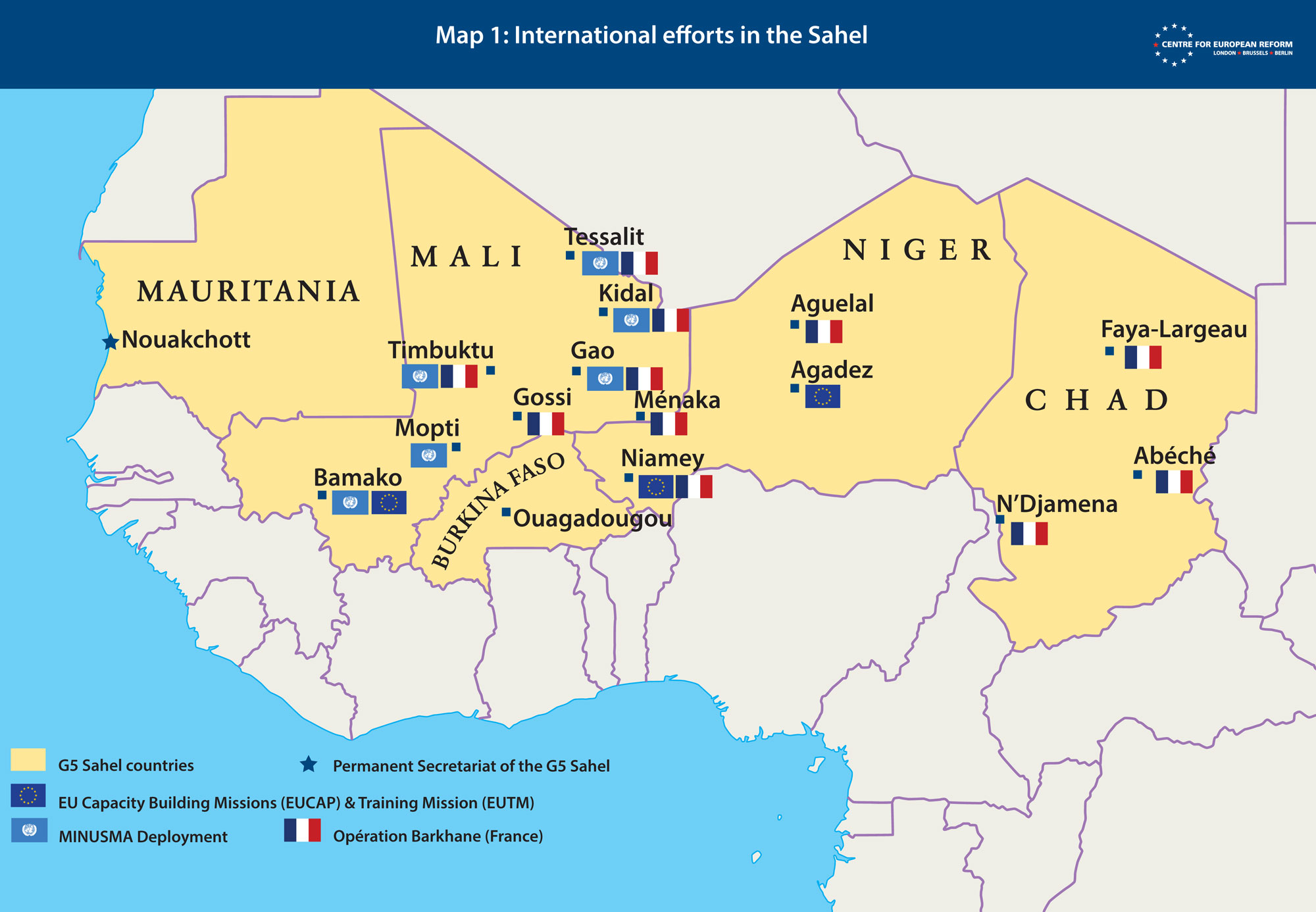

The Sahel, a region south of the Sahara desert stretching from the Atlantic coast to Sudan, is experiencing its worst escalation in violence in ten years. The Sahel includes the five states of the ‘G5 Sahel’, a regional security grouping: Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Burkina Faso and Chad (see Map 1). When the instability began in 2012-13, the conflict was primarily in northern Mali, caused by an uprising of the Tuareg and jihadist groups. However, since 2015 there has been a rapid increase of intercommunal violence between ethnic groups in central Mali. This violence has spread in recent years to Burkina Faso and Niger, with jihadist groups taking advantage of inter-ethnic tensions to recruit new members.

The Sahel is a strategic priority for Europe for three reasons. First, its location just below Algeria and Libya makes it relevant to the EU, which is seeking to limit migration flows from Africa. Many Europe-bound migrants travel through Niger and then towards the Mediterranean. Networks of smugglers have used the region’s porous borders to traffic migrants through Libya to cross the sea in boats.

Second, the presence of jihadist groups affiliated with al-Qaida and IS in the region is of great concern to Europe. France, in particular, is worried that these organisations could sponsor terrorism in Europe or attack French-owned uranium mines in Niger, which are crucial to France’s nuclear power programme. The French army has been heavily involved in counter-terrorism in Mali since the Tuareg and jihadist uprising in 2012, when it launched Opération Sérval. Sérval drove back the armed Islamist groups which had been gaining control over swathes of territory in Mali’s north and centre. In 2014, France launched Opération Barkhane, with a longer-term mandate to counter jihadist groups. French forces help troops from Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Chad – which make up the G5 Sahel’s Joint Force – to carry out counter-terrorism operations. The Joint Force, founded in 2014, brings together soldiers from the G5 states to deal with cross-border terrorist threats.

Third, the region is of wider importance to European security. The Sahel conflict is a rare example of Europe deploying not only significant resources but also political capital. The EU has been involved in development projects in the region for decades, but it had to re-direct this funding when fighting broke out in 2012. The EU now plays a role as a crisis manager in the region, with three Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions in Mali and Niger. The European Commission has adapted and boosted development funding so that it can be used for security-related purposes, and the EU has appointed a Special Representative to the Sahel, Ángel Losada, who co-ordinates diplomatic engagement with the region. As a result, Mali has been referred to as a “laboratory of experimentation” for the EU as a security actor.1 By investing so much energy and so many resources in the Sahel, the EU has given itself an opportunity to demonstrate its competence as a crisis manager to the rest of the world, and to prove it can manage instability in its own neighbourhood.

Europe is at a critical juncture in its engagement in the Sahel. Violence is at its worst since 2012, with nearly 6,500 people killed in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger in 2020 alone (see Chart 1). As a result of rising intercommunal and Islamist violence, the number of internally displaced people has increased from less than 100,000 in 2018 to 1.5 million in 2020.2 At the same time, the region has undergone significant political upheaval. In August 2020, Mali’s government was overthrown by a military coup in the wake of mass protests against corruption and the government’s inability to stop violence in the centre of the country. Discontent with governing elites in outlying regions of northern Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger is growing, as intercommunal violence worsens in these countries. The head of the French external intelligence service, the General Directorate for External Security (DGSE), recently voiced concerns that jihadist activity could spread further south to the Gulf of Guinea.

Europe can choose to continue its current approach – spending hundreds of millions of euros annually on security and development assistance, largely without tackling the root causes of the violence – or put a greater focus on longer-term commitments to good governance, public accountability and civil society. This policy brief will outline why Europe should de-prioritise costly military interventions and take the latter approach. As the EU reviews its Sahel strategy in 2021, Brussels has a particularly crucial role in facilitating a shift in strategy.

Protracted violence

Violence in the Sahel is entering its ninth year. In 2012, the Malian state collapsed in the face of a military coup and a rebellion by Tuareg ethnic groups who formed a separatist breakaway state, Azawad, in the north of Mali. The Tuareg have long desired their own independent state, and Tuareg uprisings had previously occurred in 1962, 1990 and 2007. Heavily armed Tuareg militants who had worked as mercenaries in Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya returned to Mali in 2012, triggering the rebellion. Jihadist groups formed a loose alliance with the Tuaregs and by late 2012 the armed Islamist group Ansar Dine and its allies had captured the cities of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao.

Intercommunal conflict in central Mali has spilled over into neighbouring Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger.

With the Malian government in crisis and unable to push the armed groups back, then French President François Hollande launched Opération Sérval in January 2013, a deployment of 4,000 French troops supported by US and European air cover. By the end of 2013 they had largely succeeded in recapturing all the lost territory. In 2015, the warring parties signed the Algiers accords, under the auspices of the EU, the UN, the US, France and Algeria. A main aim of the accords was to decentralise powers to the north and boost investment in the northern regions that had previously been neglected by the Malian government in Bamako. The hope was that these measures would help address the root causes of the 2012 uprising and prevent it from happening again.

The ink was barely dry on the north’s peace agreement when a new conflict in Mali’s central regions erupted in 2015-16. This time the violence primarily came from attacks by jihadists, but was rooted in frictions between ethnic communities, especially between the Dogon and the Fulani (or Peul in French) peoples. Central Mali and jihadist groups were not covered by the Algiers accords, which focused on the Tuaregs and northern Mali.

As arable land grows increasingly scarce due to the desertification of the Sahel, which is being aggravated by climate change, non-nomadic groups such as the Dogon compete with the nomadic Fulani for access to resources, providing a backdrop to tensions. In central Malian provinces such as Mopti, jihadist armed groups attacked leaders from the Dogon ethnic group (who are mostly sedentary farmers) whom they accused of supporting the Malian state. The Dogon in turn formed militias to defend themselves. But the Dogon militias frequently targeted civilians, most often from the Fulani – nomadic herders whom the Dogon accused of collaborating with the jihadists. The violence escalated over three years and reached a new height in March 2019 when a Dogon militia massacred over 160 Fulani, including women and children. Lacking protection from the state against such massacres, the Fulani then looked to Islamist armed groups for defence against Dogon attacks. Some Fulani joined the jihadists, who were happy to exploit the tensions to recruit new members. Public grievances over the Malian government’s inability to stop the violence, and rising civilian fatalities, were a driving force behind the protests in July 2020 in the lead-up to the August coup.

Intercommunal conflict in central Mali has spilled over into neighbouring Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger. Intercommunal violence and tensions over land in Mali are replicated in clashes between the Fulani and Mossi in Burkina Faso, and between Fulani, Tuareg and Daoussahak groups in western Niger. On January 2nd 2021, Islamist militants killed over 100 civilians in Tillabéri, Niger, near the border with Mali and Burkina Faso.

An internationalised conflict

France is the most important international player in the region. As the former colonial power, France sees the Sahel as its backyard. Since the 1960s France has pursued an approach of Françafrique: fostering close political, economic and military links between French and francophone African elites, and long-term defence agreements with all the Sahelian countries. This engagement included frequent interventions during the Cold War. France took military action in francophone Africa 19 times to support governments between 1962 and 1995.3 No French president has managed to pull France’s forces out of Africa, despite its citizens’ growing disenchantment with military engagement in the region. President Hollande tried, and failed: he ended up launching Opération Barkhane, which currently stands at 5,100 personnel.

The UN is also heavily involved in the Sahel. With over 14,000 uniformed personnel currently deployed, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is the UN’s second-largest peace-keeping mission after UNMISS in South Sudan. MINUSMA’s mandate is to support the peace process in Mali, including the implementation of the 2015 Algiers accord in the north; to promote national dialogue and reconciliation; to protect civilians and reinstate government authority in central Mali; and (most recently) to support the political transition following the August 2020 coup.

Urged on by France, other European countries and the EU have started to play a more active role in the region. Seventeen EU member-states now contribute soldiers or police to MINUSMA.4 Following the 2015 refugee crisis, Germany has taken an increased interest in the area and has stepped up its troop commitments. Germany now sends 1,500 troops to the EU’s military CSDP mission in Mali and MINUSMA, and Berlin recently gifted 15 armoured vehicles to the Nigerien armed forces. Meanwhile Estonia, Sweden, Denmark, the UK and the Czech Republic contribute to Opération Barkhane. Five more EU member-states plus the UK have also agreed to support the new French-led international counter-terrorism Task Force Takuba.5 The Task Force will enable European special forces to accompany Malian and Nigerien forces on counter-terrorism assignments in cross-border regions from 2021.

Better co-ordination between donors has not brought Europe much success in de-escalating the violence.

The EU currently has two overseas missions in Mali as part of the EU’s CSDP – a military training mission for the Malian armed forces (EUTM Mali) and a civilian and law enforcement capacity building mission (EUCAP Sahel Mali). The EU has a similar capacity building mission in Niger to help the authorities there counter migration flows (EUCAP Sahel Niger).6 Europe also plays a prominent role in managing the conflict through its international development aid. EU development funds are now allocated to security-related projects such as stabilising local administrations and carrying out border surveillance missions. The Sahel Alliance, founded in 2017 at the initiative of France, Germany and the EU, has been the primary mechanism for co-ordinating development and security activities.7 The Alliance structures projects around shared priorities and acts as a point of contact on development for the G5 Sahel countries, funding 880 projects worth €11.6 billion.

Since 2011 there has been a plethora of strategies and action plans from France and the EU. While they differ in their exact focus, they all prioritise shorter-term interests in curbing migration and counter-terrorism. The EU Strategy for the Sahel 8 and the Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015-20 9 set out the EU’s interests in the region since instability began in 2012. Migration took on increased prominence in the Sahel Regional Action Plan in light of the 2015 refugee crisis. By contrast, good governance is given a low priority, and the documents do not elaborate much on what the phrase means, beyond improving the provision of public services. The EU is currently reviewing its Sahel strategy in 2021.

Despite the approaches set out in the EU’s Sahel strategy, and the increased resources dedicated to development in the region, violence has continued to worsen in central Mali in the last four years. In 2019 French President Emmanuel Macron announced the Partnership for Security and Stability in the Sahel jointly with Germany. This aimed to provide a greater focus on law and order and governance, and less on traditional security goals. But the Partnership was never implemented because less than a year later in January 2020 another structure – the Coalition for the Sahel – was launched by France. The Coalition is supposed to concentrate all European action around four pillars: counter-terrorism; building regional military capacity; supporting the return of state authority; and development.10 Yet better co-ordination between donors has not brought Europe much success in de-escalating the violence. While European strategies have increasingly mentioned the importance of good governance as a long-term solution to the conflict, in practice the status quo largely prevails. Europe’s focus remains on supporting states with development assistance, combined with short-term efforts to neutralise terrorist groups.

The UK has also bolstered its presence in the region. Having opened an embassy in Mali after the 2012 coup, Britain expanded its presence in Bamako and opened embassies in Niger and Chad in 2018. Despite the major cuts proposed for its aid budget, the UK government is so far maintaining its commitment to the Sahel Alliance and reaffirmed the region’s importance in the 2021 UK Integrated Review.11 As well as dedicating Chinook helicopters to Opération Barkhane, in December 2020 the British government sent 300 troops to MINUSMA. France and the UK have similar strategic cultures: an expeditionary impulse and a willingness to undertake overseas military engagements, which makes Franco-British military co-operation in the Sahel effective.

The US also plays an important role in supporting Barkhane, particularly with intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, and air-to-air refuelling capabilities. The US operates a drone airbase in Niger, with around 800 troops currently in the country. While there were fears that Trump would follow his withdrawal of US support to Somalia by a similar move in the Sahel, ultimately he did not. But the Sahel is not a priority for the Biden administration, so an increase in US military engagement is still unlikely. Meanwhile China has been quietly stepping up its commitments to MINUSMA, and sits just behind Germany as a troop contributor, with 413 Chinese soldiers in the mission. This mirrors China’s increased pledges to UN peace-keeping and its security commitments in Africa, which now range from South Sudan to its military base in Djibouti. China has equally been investing in Mali’s infrastructure and services, including the rehabilitation of a colonial-era railway line between Bamako and Dakar, Senegal.

Despite Europe’s huge investments, the security situation in the Sahel has deteriorated drastically.

Russia and Turkey are also looking for opportunities to expand their influence in the Sahel. Turkey has raised development spending via the Turkish Co-Opération and Co-ordination Agency in the region, and also denounced Opération Barkhane as neo-colonial.12 Turkey signed a security agreement with Niger in July 2020, to increase bilateral co-Opération to counter any spill-over of the Libyan conflict (in which Turkey is heavily involved). In September 2020 Turkey’s Foreign Minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, made a trip to West Africa, including to Mali, and reaffirmed Turkey’s commitment to the region’s security. Russia meanwhile has co-Opération agreements with Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger on military training and counter-terrorism. The Wagner Group of Russian mercenaries, known to be active in Libya and the Central African Republic, allegedly also has a presence in Mali.13

Neither Russia, Turkey nor China, however, have anything approaching Europe’s experience or potential clout in the region, nor do they match the scale of Europe’s commitments. Opération Barkhane cost an estimated €695 million in 2019 and as much as €911 million in 2020. Meanwhile EUTM Mali’s combined budget for 2020-24 has increased to €133.7 million. EUCAP Sahel Mali’s budget for the period 2021-23 increased to €89 million and EUCAP Sahel Niger had a budget of €63.4 million for the years 2018-20. MINUSMA has the highest annual budget of any UN mission in the world, at $1.18 billion in 2020-21, with substantial contributions from EU member-states such as Germany.

Yet despite Europe’s huge investments, the security situation in the Sahel has deteriorated drastically. In France, intervention fatigue is growing. Fifty-seven French soldiers have been killed since 2013, including five who died in Mali in the first week of 2021. A January 2021 poll taken after the deaths of these troops found that 51 per cent of French citizens no longer support French intervention in the Sahel.14 At the G5 Sahel Summit in February 2021, Macron went to great lengths to show that Barkhane’s success is integral to European security and that its burden is being shared by other European partners. But the EU’s approach of capacity building, security sector reform and financing development projects is also proving inadequate for stabilising Sahelian societies. The EU’s Special Representative Losada recently commented that the EU must renew its strategies to meet new needs and admitted that there had been failings in the EU’s approach, highlighted by the August 2020 coup in Mali.15

State security forces: Part of the problem?

European support to Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso prioritises assistance to the defence and security sector to help it deal with threats from Islamist armed groups. Attacks from jihadist groups are mostly concentrated in the ‘tri-border region’ between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, so France has rightly encouraged transnational security co-Opération through the G5 Sahel Joint Force.

Opération Barkhane, the EU’s training and capacity building missions and MINUSMA have done reasonably well at achieving their shorter-term objectives, providing much needed technical support and training to Sahelian armed forces. Barkhane in particular has been effective at killing the leaders of armed Islamist groups, and has achieved numerous tactical victories. In November 2020 for instance, French forces killed the military leader of JNIM, Bah Ag Moussa, during a clash in southeastern Mali. Having built close partnerships with Sahelian security forces, Europe’s strategy is to build up the capacity of their partners to carry out such raids autonomously.

In support of Barkhane, EUTM Mali has now trained over 15,000 soldiers to deploy in small tactical units and to hold their positions under enemy fire. EU civilian capacity building missions in Mali and Niger have become important partners to internal security forces in combatting cross-border crime. The EU is also helping Malian armed forces to establish a presence in isolated areas of central Mali that are plagued by jihadist violence, such as the Pole Sécurisé de Développement et de Gouvernance (PSDG) in Konna, central Mali.16 MINUSMA has managed to maintain a fragile peace with Tuareg groups in the north.

Mistreatment by security forces and state institutions is one of the most powerful drivers of jihadist recruitment.

Europe’s security-focused approach, which prioritises training the militaries and internal security forces of Sahelian countries, would seem at first glance to be sensible. It is a primary function of the state to protect its citizens against violence from militias and armed insurgent groups, and Sahelian armed forces are best placed to deal with these challenges in the long term. Terrorism is the greatest security threat to Europe in the region, so Europe’s focus on it is understandable. In the post-Afghanistan era, when European publics are weary of open-ended military engagements, intervening countries need to provide clear benchmarks for withdrawal. For France, this means that once certain targets in terms of training and the capacity of Sahelian armies to fight terrorist groups have been met, they will leave.17

The problem with this approach, however, is that frequently the states which receive millions of euros of security assistance every year are the same ones whose national armies carry out illegal killings, torture and other human rights abuses against their own populations. For many communities in the Sahel, not only do state security forces fail to protect them from violence, but they actively pose a threat to their safety. The same Malian army that received training in human rights from EUTM Mali was implicated both in Mali’s August 2020 coup and human rights violations in the centre of the country. The more the state is perceived as a perpetrator rather than a mediator of inter-ethnic disputes over land or a provider of security, the more civilians will seek protection from Islamist armed groups or ethnic militias, and the cycle of violence will continue.

While in 2019 the majority of the civilian fatalities in the region were caused by attacks from Islamist armed groups or intercommunal violence, there is a worrying trend toward state-perpetrated violence, as shown by Chart 2. MINUSMA’s human rights division recently found that in the third quarter of 2020 Mali’s security forces carried out more human rights abuses than any other actor.18 The West Africa director at Human Rights Watch has argued that these illegal killings constitute war crimes.19 These abuses, especially indiscriminate attacks on the Fulani by state security forces, are driving people to turn to jihadist groups for protection, and the Islamists are all too happy to exploit intercommunal tensions opportunistically to swell their own ranks. Studies have repeatedly found that the experience of mistreatment by security forces and state institutions is one of the most powerful drivers of jihadist recruitment in the region.20

Europe should also be more concerned about Malian, Nigerien and Burkinabe state affiliations with ethnic militias as proxies. These militias have carried out massacres against the Fulani, worsening inter-ethnic tensions. In January 2020, Burkina Faso passed the ‘Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland Act’, which allowed the state to arm civilians to fight jihadists. Yet in the nine months after the legislation, more than half of the 19 attacks launched by volunteers were against civilian members of the Fulani community, who were accused of collaborating with the jihadists.21 In the past the Malian state has similarly been accused of collaborating with hunting groups called Dozo to fight jihadists, and Dozo have also targeted Fulani civilians.22 Nigerien authorities have meanwhile failed to prevent Tuareg militias from targeting Fulani communities in the western Tillabéri province.

Europeans have become more vocally critical of abuse by security forces in the Sahel. French Defence Minister Florence Parly said human rights abuses by state security forces “could threaten international support.”23 EU High Representative Josep Borrell has denounced the conduct of G5 forces.24 Yet there has been no talk of withdrawing funding from, or sanctioning, those who have perpetrated human rights abuses. Nor were questions raised about the effects of the EUTM’s training programmes in human rights on the behaviour of Mali’s armed forces. When Human Rights Watch presented evidence of a mass execution of 180 Fulani civilians by Burkina Faso’s army in June 2020, the EU’s response was only to demand that the Burkinabe authorities shed light on these allegations, reiterating European support for the army’s counter-terrorism campaign.25

Europe needs to prioritise tackling abuses by Sahelian armed forces for two reasons. First, without sanctions for misconduct and greater pressure to prevent these incidents, G5 militaries will have little incentive to change their ways. Europe’s efforts to achieve stability by supporting state security forces will become increasingly counter-productive. The only real path to solving the intercommunal violence in central Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger is if state authorities in these countries can act as a mediator in disputes (often over land) between communities – which jihadist groups would be happy to do in their absence. The state cannot carry out this function if it is feared and mistrusted by certain communities, such as the Fulani. It is in Europe’s interest that governments in the Sahel rebuild trust with all communities and cease to be seen as partisan in inter-ethnic conflicts they are supposed to be resolving.

Second, if European-funded armies in the Sahel have played a part in worsening and prolonging the conflict, the basis of Europe’s ‘capacity building’ strategy could be called into question. European parliaments and citizens have the right to question if the millions of euros being spent by their governments on security assistance are further destabilising the region. Paris and Brussels may fear that threatening sanctions will lead the G5 to reject European aid or make less effort to counter illegal migration. But given the importance of foreign military aid to state security sectors in the Sahel, this argument underestimates Europe’s bargaining power.

The ‘return of the state’: Not an end in itself

Development co-Opération is the other key arm of Europe’s engagement in the Sahel. The EU promotes the concept of the ‘security-development nexus’, or the idea that security and development are intrinsically linked. This nexus emerged as part of Europe’s response to the 2015 refugee crisis and allows the EU to mobilise development projects towards goals such as preventing violent extremism or limiting migration.

In the absence of public services and protection, jihadists also use the provision of services to win over the local population.

EU development efforts aim to facilitate the ‘return of the state’, a phrase which has become a central focus of European projects in the Sahel. The European Commission, national development agencies and leaders such as Emmanuel Macron have rightly drawn attention to the lack of security, access to justice, law enforcement and basic public services for civilians. This was a central cause of the 2012 Tuareg uprising in northern Mali. In the absence of public services and protection, jihadists also use the provision of services to win over the local population, for instance by building Qur’anic schools and by presenting themselves as a more legitimate, less corrupt alternative to a predatory state. Western powers seek to combat this by inserting government administration and public services back into areas affected by violence.

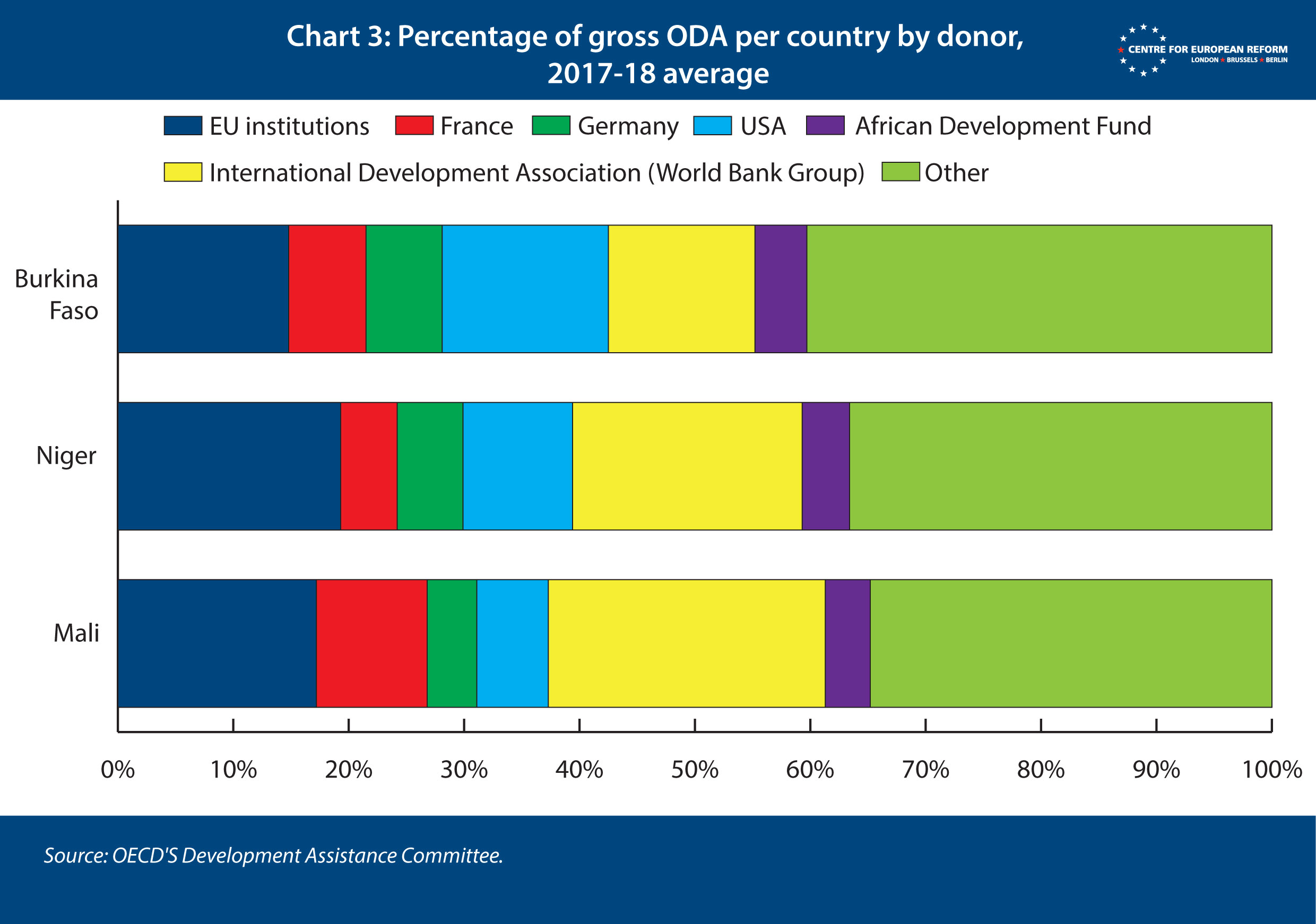

At France’s initiative, the EU and its member-states have increased investment in public services, infrastructure and the capacity of state institutions. As shown by Chart 3, Europe is responsible for a significant portion of the region’s overall development funding. The Sahel Alliance’s 2021 report showed that of the €17 billion already disbursed, nearly a third was dedicated to extending health coverage, improving access to drinking water, building better roads and ensuring that as many children as possible attend school, as well as other services.26

A policy of ‘returning the state’, however, will not in itself build trust between governments and the wider population. Long-term peace will depend more on whether the state serves the interests of all its citizens. While European projects promote good governance on a technical level by helping to build schools and other public services, if citizens see the returning state as corrupt and self-serving, the pay-off Europe gets from these investments will be reduced. Mali and Niger rank particularly poorly on corruption, at 129th and 123rd place respectively, out of the 180 countries on Transparency’s Corruption Perception Index in 2020. Their governing elites have been embroiled in scandals from cronyism to the misuse of public funds. But so far, the EU remains reluctant to use its leverage as a donor to attach strict governance and rule of law indicators to its funding, partly because it considers its partnerships with Sahelian countries important as a means of limiting migration.

A 2020 audit in Niger found that at least $137 million of public money had been lost over the past eight years – roughly ten per cent of the total defence budget over that period – due to corrupt contracts for military equipment.27 Outrage from the public and civil society groups led to mass protests in the capital Niamey in March 2020. In response, the Nigerien authorities used brutal force on the crowds. The journalists who uncovered the story were later arrested. Yet neither France nor the EU condemned these events, despite the high probability that European aid money had also been embezzled. The EU went ahead with launching €112 million in additional funding to the G5 Sahel defence sector the following month. Europe’s silence reinforced the idea among Nigerien protestors that European donors were complicit with a corrupt national elite. The EU has also been criticised for its inability to discuss democratic backsliding in Niger and the authoritarian tactics of President Mahamadou Issoufou, whom Europe has valued as a key partner for counter-migration measures.28 While Issoufou recently agreed to step down after the end of his second term, February’s elections were marred by accusations of fraud and followed by violence and an internet shut-down.

The extreme dissatisfaction of Malian citizens with their government led to similar protests last year. Mass civil unrest led to the overthrow of Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta in August 2020. Keïta had long been seen as corrupt and nepotistic, failing to tackle intercommunal violence in central Mali or to dedicate adequate resources to public services. Demonstrations broke out in June 2020 when Mali’s Constitutional Court nullified the parliamentary election results, to the benefit of the President’s ruling party. Protestors demanded an end to the impunity of ruling elites and corruption scandals. One poll of Malian citizens in August 2020 found that up to 88 per cent favoured the removal of President Keïta.29 The government’s crackdown on protestors resulted in 14 people being killed in July, yet Europe’s response was muddled and delayed. Up to that point, the EU had seen Keïta’s regime as an important ally on counter-terrorism and migration. While Borrell condemned the killing of protestors, the EU continued to refrain from overt criticism of Keïta’s regime or to engage with the demands of the protestors. Europe missed a valuable opportunity to build momentum for the reform of Mali’s democratic system.

Many citizens of the Sahel do not find the return of the state in itself a desirable outcome.

An awkward truth for Europe is that many citizens of the Sahel do not find the return of the state in itself a desirable outcome. A broken social contract, a lack of trust in public institutions, neglect of public services and prominent corruption scandals mean that many citizens would prefer to have less corrupt institutions rather than to restore or reinforce them. The July 2020 protests in Mali were a reminder of public resentment against governing elites which had bubbled under the surface for years. But European donors do not yet seem to fully appreciate the extent to which popular disenchantment with governing elites could lead to further civil unrest and instability, which in turn will undermine European stabilisation efforts in the long term.

It is understandable that France and the EU are reluctant to take positions on sensitive issues concerning the domestic politics of Sahelian states. France wants to avoid being accused of neo-colonialism by intervening in the internal affairs of G5 countries.30 Particularly in the post-Afghanistan era, France fears becoming embroiled in domestic politics in the Sahel, which could make it more difficult to eventually leave.31 France has had a history of supporting strongmen in Africa as part of Françafrique, reinforcing authoritarian governments as bulwarks against populist movements which Paris saw as destabilising. At the February 2021 G5 Sahel summit, President Macron repeatedly emphasised that France was in the region at the behest of Sahelian states to help them with their security issues, not the other way around.

If their current approach continues, however, France and the EU will be accused of neo-colonialism anyway. When Macron called the Pau summit to discuss the future of security assistance in the Sahel in January 2020, anti-French protests were in full swing. Some protestors carried Russian flags, called for Putin to help Mali and shouted for France to ‘go home’.32 Similar protests also took place in Bamako in January 2021 against Opération Barkhane. France and Europe are increasingly seen as partners to corrupt national elites who profit from international funds while violence and poverty outside the capitals get worse.

Civil society groups have helped to spearhead popular protests against corruption in Mali and Niger and enjoy widespread support from most communities in the Sahel.33 The EU is an important partner to civil society organisations in Mali and has helped build their capacity through funds and training. But the arrest of prominent Malian anti-corruption campaigner Clément Dembélé in May 2020 and of the Nigerien journalists who uncovered the military contracts scandal shows that that civil society groups need more leverage to pressure governments to carry out reforms. Opportunities for civil society to publicly discuss their proposed solutions with international partners have been limited and ad hoc. EU Special Representative Losada, for instance, has focused on raising awareness about the conflict among EU member-states and high-level diplomatic engagement with G5 Sahel governments – rather than on civil society.

Recommendations

- Europeans must make continued financial and military support conditional on states ending the abuses of armed forces against civilians and state affiliations with ethnic self-defence groups.

France and the EU should consider imposing sanctions on military officials who are involved in abuse against civilians. Europeans should also suspend portions of military aid if armed forces violate human rights or fail to cut ties with ethnic self-defence groups. Continuing to fund G5 militaries without taking steps to ensure their accountability is counter-productive to Europe’s aims of stabilising the region. - Europe should make aid and security assistance more conditional on anti-corruption measures, including good financial account-keeping, better public audits and transparency.

European donors should also push for the prosecution of individuals involved in corruption and the misappropriation of funds. Such steps could help avoid a repeat of incidents such as Niger’s military contracts scandal in 2020. Some observers have highlighted particular opportunities to do this in Mali this year: since large tranches of assistance have been frozen since the August 2020 coup, European partners could tie the release of funds to action plans for financial transparency and accountability.34

European partners could tie the release of funds to action plans for financial transparency and accountability.

- The EU should place greater emphasis on engagement with civil society.

The EU should consider holding regular conferences with civil society organisations, which would give their demands a platform and strengthen civil society networks across the region. The EU already does this with Eastern Partnership countries, for which it hosts an annual Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum to bolster democratic participation and the reform process. EU Special Representative Losada could also play a particularly valuable role. He should take more opportunities to engage with the demands of civil society groups, including on fighting corruption, and should speak out against crackdowns on freedom of speech. Supporting popular anti-corruption civil society groups would not only boost Europe’s credibility as a partner but also help foster a culture of participation in Sahelian societies and strengthen democratic accountability. - Given its recently boosted commitments to security in the Sahel, the UK should use the region as a key arena for building practical post-Brexit military and development co-operation with EU partners.

Building up experience of working together on the ground would add a practical dimension to Franco-British military co-operation as outlined in the Lancaster House Treaties and Macron’s European Intervention Initiative, which has been designed to provide a non-EU format for states with similar strategic cultures to work together. The UK’s 2021 Integrated Review commits the UK to continuing to support French counterterrorism operations in the Sahel.

Conclusion

Europe will always have strong interests in the security and stability of the Sahel region. Geographically it is part of Europe’s wider neighbourhood, and against a background of escalating violence in the region both the EU and its member-states are anxious to avoid a repeat of the refugee crisis of 2015. France’s strong focus on counter-terrorism will similarly keep it engaged in the Sahel for the foreseeable future. But what Europe gets back from this engagement depends on how it reshapes its strategy at this critical juncture. As the EU reviews its Sahel strategy, its future success as a crisis manager depends on it reordering priorities, so that it puts accountability and good governance ahead of building the capacity of the security forces.

Europe’s approach so far has done little towards achieving a lasting solution to the problem of insecurity. European strategies are designed to address migration flows and terrorism. But these problems are only the symptoms of deeper-rooted instability. As a consequence, Europeans are in danger of playing whack-a-mole with raids against jihadist groups, which will continue to return so long as intercommunal tensions and mistrust of government persist. France and the EU know that they need to engage with questions of governance, justice and accountability; their importance is now consistently mentioned in European strategies. But Europeans will be wary of articulating any substantive ideas for the political future of the region, or of making ambitious rhetorical commitments that are hard to implement. State-building in Afghanistan has shown few signs of success after 20 years of international efforts.

Rather than seeking to impose any top-down vision for the region, the best path for Europe is to engage with civil society and help build trust between governments and their citizens, so that a process of reconciliation can begin. The EU will need to impose strict conditionality on governments and security forces in the region, to ensure its interventions do not make the conflict worse. This approach could also force Europe to consider difficult compromises, such as whether to put a lower priority on migration in EU strategies, vis-à-vis the importance of good governance. But such shifts may be necessary in order to stop violence and eliminate the conditions that drive irregular migration and terrorism. While France, as the former colonial power, says it is reluctant to engage with the domestic politics of the Sahel, the EU is well placed to play such a role. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has maintained that engagement with civil society and greater focus on good governance will be central to the new EU-Africa strategy. Given that the EU already has a strong presence in the region, the Sahel would be an excellent place to set this new approach in motion.

A traditional argument for backing state security forces and strongmen in Africa is that they ‘get the job done’; they have the means to impose stability through force and ensure that violence does not spread across a region. But Europe’s track record in the Sahel suggests that a security- and state-centric approach has not only failed to stop a catastrophic escalation in the violence – 2020 was the deadliest year since the violence began in 2012 – but also has proved that backing regimes that commit atrocities against their civilians undermines stability. Abuses and corruption by governments are driving recruitment to jihadist groups, causing civil unrest and perpetuating the conflict. There is no contradiction in the Sahel between the EU’s interests in ending the conflict and its values such as democratic governance, accountability and the rule of law. Unless the EU lives up to these values, and does more to ensure that its regional partners do the same, conflicts will continue. The sooner Europeans realise this, the better.

2: Danish Refugee Council, ‘Central Sahel is rapidly becoming one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises’, November 11th 2020.

3: Shaun Gregory, ‘The French military in Africa: Past and present’, African Affairs, vol. 99 no. 396, 2000.

4: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain and Sweden.

5: Kalev Stoicesu, ‘Stabilising the Sahel: The Role of International Military Opérations’, International Centre for Defence and Security – Estonia (RKK ICDS), July 2020.

6: Twenty-two EU member-states currently contribute to EUTM Mali and 13 member-states to the EUCAP Sahel civilian missions.

7: Eight European countries (including France, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK), the EU, the World Bank and UNDP are among its members.

8: European Union External Action Service, ‘Strategy for Security and Development in the Sahel’, March 2011.

9: Council of the EU, ‘Council conclusions on the Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015-2020’, April 20th 2015.

10: Andrew Lebovich, ‘Disorder from chaos: Why Europeans fail to promote stability in the Sahel’, European Council on Foreign Relations, August 26th 2020.

11: ‘Global Britain in a competitive age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, HM Government, March 2021.

12: Samuel Ramani, ‘Turkey’s Sahel strategy’, Middle East Institute, September 23rd 2020.

13: Kimberly Marten, ‘The GRU, Yevgeny Prigozhin, and Russia’s Wagner Group: Malign Russian Actors and Possible US Responses’, Testimony before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment, United States House of Representatives, July 7th 2020.

14: Guerric Poncet, ‘Sahel: La moitié des Français opposés à la présence française’, Le Point, January 11th 2021.

15: Centre for Strategic and International Studies Sahel Summit, October 16th 2020.

16: The PSDG is a base for 120 National Guard members which will allow state security forces to protect civilians better and will provide an outpost for public authorities such as judges and administrators to re-establish local authorities and a justice system in the centre of the country.

17: Interview with an official from the French ministry of defence.

18: MINUSMA, ‘Note sur les tendances des violations et abus de droits de l’homme au Mali’, January 2021.

19: Corinee Dufka, ‘Sahel: “Les atrocités commises par des militaires favorisent le recrutement par les groups armés”’, Le Monde, June 19th 2020.

20: ‘If victims become perpetrators: Factors contributing to vulnerability and resilience to violent extremism in the central Sahel’, International Alert, June 2018.

21: Sam Mednick, ‘Victims or villains? The volunteer fighters on Burkina Faso’s front line’, The New Humanitarian, October 12th 2020.

22: ‘Reversing central Mali’s descent into intercommunal violence’, International Crisis Group, November 9th 2020.

23: ‘Abuses by G5 soldiers in Sahel ‘could threaten international support’’, Radio France Internationale, June 19th 2020.

24: European External Action Service, ‘Mali: statement by the High Representative / Vice President Josep Borrell on the latest developments in the centre of the country’, June 10th 2020.

25: EU Delegation to Burkina Faso, ‘Déclaration locale de L’Union européenne au sujet du meurtre du Maire de Pensa (Centre-Nord) et du récent Rapport de Human Rights Watch évoquant de possibles exactions des Forces de Défense et de Sécurité’, July 9th 2020.

26: Programmes include a €84 million EU Health Sector Policy Support Programme in Burkina Faso to help extend health insurance coverage to all citizens and an EU project worth €90 million dedicated to improving access to schooling for all Nigerien citizens. The European Commission is helping fund a 300km road between Gao and Kidal to better connect the northern regions of Mali to the rest of the country.

27: Jason Burke, ‘Niger lost tens of millions to arms deal malpractice, leaked report alleges’, The Guardian, August 6th 2020.

28: Wesley Dockery, ‘Niger: The EU’s controversial partner on migration’, Info Migrants, August 17th 2018.

29: Halima Gikandi, ‘After military coup, uncertainty hangs over Mali’s future’, The World, September 1st 2020.

30: Michael Shurkin, ‘France’s War in the Sahel and the Evolution of Counter-Insurgency Doctrine’, Texas National Security Review, Winter 2020/21.

31: Christophe Ayad, ‘Le Mali est notre Afghanistan’, Le Monde, November 16th 2017.

32: Laurent Ribadeau Dumas, ‘La Russie exerce-t-elle une influence au Mali?’, Franceinfo: Afrique, November 21st 2019.

33: Aurelien Tobie, ‘A fresh perspective on Civil Society concerns among Malian civil society’, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, July 2017.

34: ‘A Course Correction for the Sahel Stabilisation Strategy’, International Crisis Group, Africa Report No. 299, February 1st 2021.

Katherine Pye is the 2020-21 Clara Marina O’Donnell fellow at the Centre for European Reform

View press release

Download full publication