The EU needs a bigger playing field – not a level playing field

- European policy-makers increasingly see the EU’s commitment to open markets as naïve. They are concerned about the constraints EU firms face when competing, in the EU or abroad, with businesses from the EU’s major trading and investment partners – especially, but not exclusively, China.

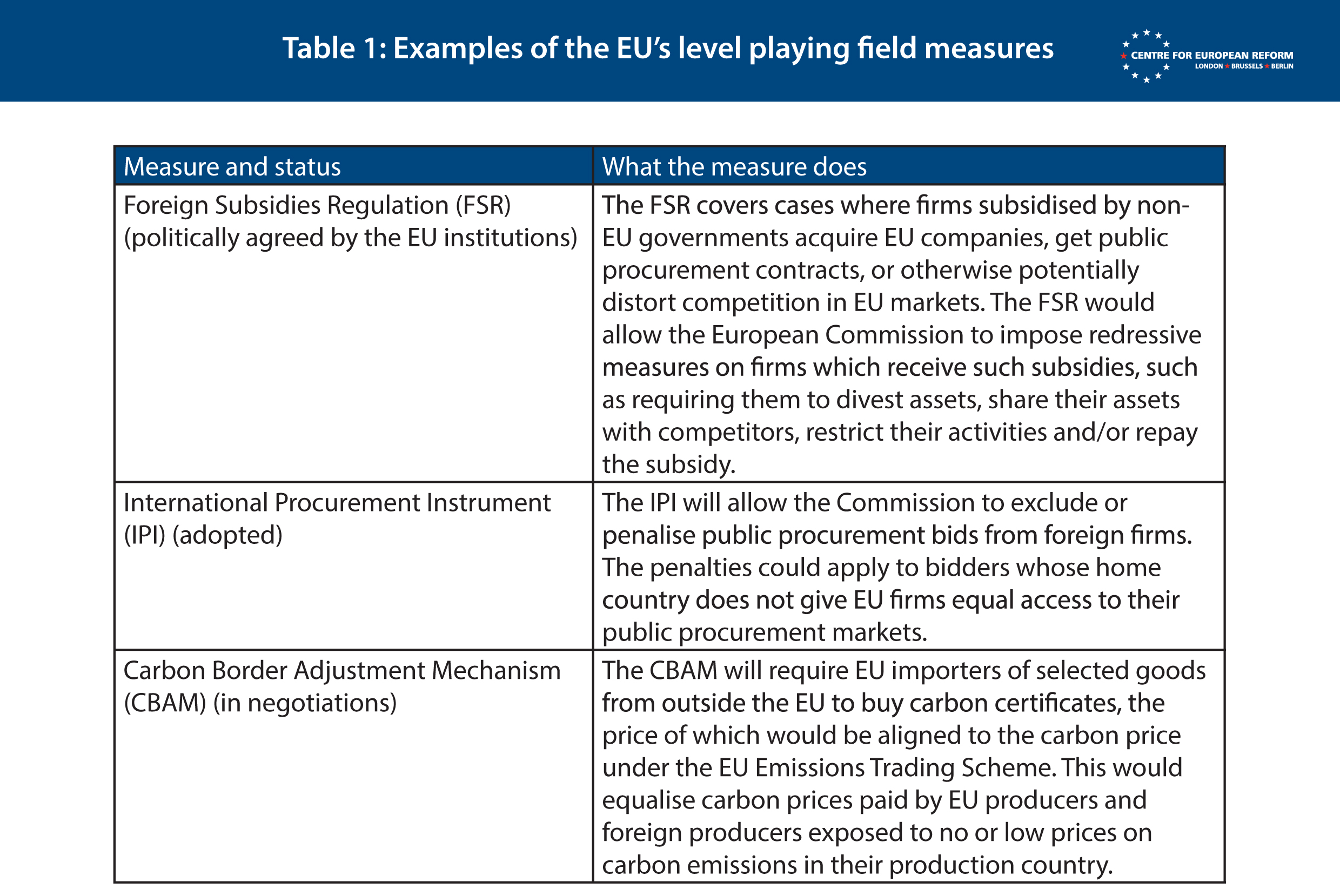

- To tackle this problem, the EU is developing instruments to unilaterally limit or regulate some foreign companies’ access to its market. For example, the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) would allow the European Commission to discipline firms which receive foreign subsidies that distort competition in the EU; and the International Procurement Instrument (IPI) could limit foreign companies’ ability to win EU public contracts unless EU firms have fair rights to bid for public contracts in the foreign company’s home country.

- When these measures were first envisaged, in some cases more than a decade ago, the EU saw them as part of a broad strategy to increase trade and investment with China on fairer terms. Given the West’s growing rivalry with China, the EU now has different priorities. It needs to strengthen its internal market, and build trading and investment partnerships with countries which pose less political risk.

- On the domestic front, some of the instruments risk weakening, rather than strengthening, the EU internal market by being insufficiently targeted. This means they could limit beneficial inward investment and unnecessarily increase the uncertainty and costs of doing business in the EU.

- Despite this downside, the EU’s new unilateral tools could still be beneficial overall if they help to open up new opportunities for EU firms in foreign markets with greater growth prospects than Europe. To achieve this, the instruments must be used surgically and strategically. They should be used to seek more open trade and investment with countries like the US and India, which are protectionist but also pose less political risk than China.

- The EU should take the opportunity to tweak those proposals which have not yet been finalised, to reduce the risk that they unnecessarily limit investment and competition in the EU, and to better facilitate pragmatic compromises with foreign countries. And the Commission should do its best to ensure the level playing field instruments are deployed as negotiating leverage to diversify the EU’s economic relationships, rather than to protect EU businesses. Using the instruments sparingly will be essential to their effectiveness.

Open markets have helped the EU become one of the most prosperous regions in the world – enjoying significant inward foreign investment and high levels of competition. Foreign firms are generally free to export to the EU, participate in its single market, acquire EU firms and win European public procurement contracts. Yet leaders of some of the EU’s most influential member-states now see the EU’s commitment to open markets as naïve, or at least believe that the EU would benefit from a more closely managed trade and investment policy.

They are concerned that other countries are taking unfair advantage of Europe’s openness in several ways. First, other countries often have more protectionist domestic regulation – meaning that European firms have less access to foreign markets than foreign firms enjoy in the EU. Second, when foreign firms compete in Europe, they may have advantages European firms lack – such as state subsidies that would be banned under EU state aid law or protection from competition in their home market. Third, foreign firms may also operate in a looser regulatory environment, for example producing goods or services in jurisdictions with fewer concerns about the environment. Some of these concerns apply even to the EU’s closest global partners – EU leaders were dismayed when the US recently strengthened its Buy American Act, which privileges US firms in public procurement processes. However, in general, European concerns have been focused on China.

The EU has new trade and investment priorities – and the EU’s level playing field instruments need to be assessed against them.

In response, the EU has started developing instruments to address these problems unilaterally, examples of which are summarised in Table 1. A number of these instruments were first conceived more than a decade ago. But as global tensions have increased, pressure to adopt the instruments has increased. As recently as 2019, the tools were meant as part of a broader strategy to secure more access to China’s closed markets. They would have been coupled with the now defunct EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), which would have prevented China rolling back much of the market access it already allows European firms. Since then, the political and economic environment has changed drastically. China-EU relations have hit a low point, due to disputes over China’s crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong, its actions in the South China Sea and its human rights record in Xinjiang; China’s zero-Covid strategy, which is rocking global supply chains; and China’s unwillingness to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2019, the European Commission famously called China a “co-operation and negotiating partner”, “economic competitor” and “a systemic rival”.1 Now, rivalry is predominant.2 In 2021, the EU sanctioned certain Chinese officials in connection with human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and China responded with its own countersanctions. MEPs have refused to ratify the CAI and in light of the difficulties Europe now faces in trying to rapidly cease its reliance on Russian fossil fuels, politicians across the EU are starting to consider, if not decoupling, then at least taking a less opportunistic approach to trade with the West’s rivals.

For this reason, the EU now has different trade and investment priorities – and the EU’s level playing field instruments need to be assessed against these new priorities. First, the instruments need to strengthen the EU’s internal market. Currently, the US could tolerate decoupling from China far better than Europe would, in large part because America can increase production of important inputs like computer chips faster than the EU, which is still heavily reliant on east Asia.3 Second, the instruments should help the EU to strategically open overseas markets – thereby diversifying the EU’s trade and investment with countries that pose less political risk.

Can the level playing field instruments strengthen the EU internal market?

The Commission’s primary stated goal in pursuing these instruments is to create a level playing field when foreign firms compete in Europe. The Commission believes the European market will be strengthened if distortions of competition – such as those that foreign firms may enjoy – are removed. But this will only strengthen the EU internal market if the measures target conduct which is actually harmful – otherwise it risks obstructing beneficial investment. The measures also need to avoid creating large compliance costs for all foreign businesses, to help keep Europe comparatively attractive for foreign investment. As currently planned, the EU’s level playing field measures do not meet either of these criteria.

Do the level playing field instruments target practices harmful to the internal market?

Foreign direct investment (FDI) brings many benefits to Europe – such as giving Europe access to foreign technology and know-how and boosting local employment. Exports to the EU are also valuable – they improve competition and lower prices for EU customers. Neither should automatically be viewed with suspicion.

The participation of foreign firms in the EU internal market is only harmful in a few cases, most of which can already be addressed to some degree by the EU. The level playing field instruments need to focus on fixing loopholes in existing laws, or addressing broader global problems like carbon emissions, rather than applying wide-ranging prohibitions on incoming investment.

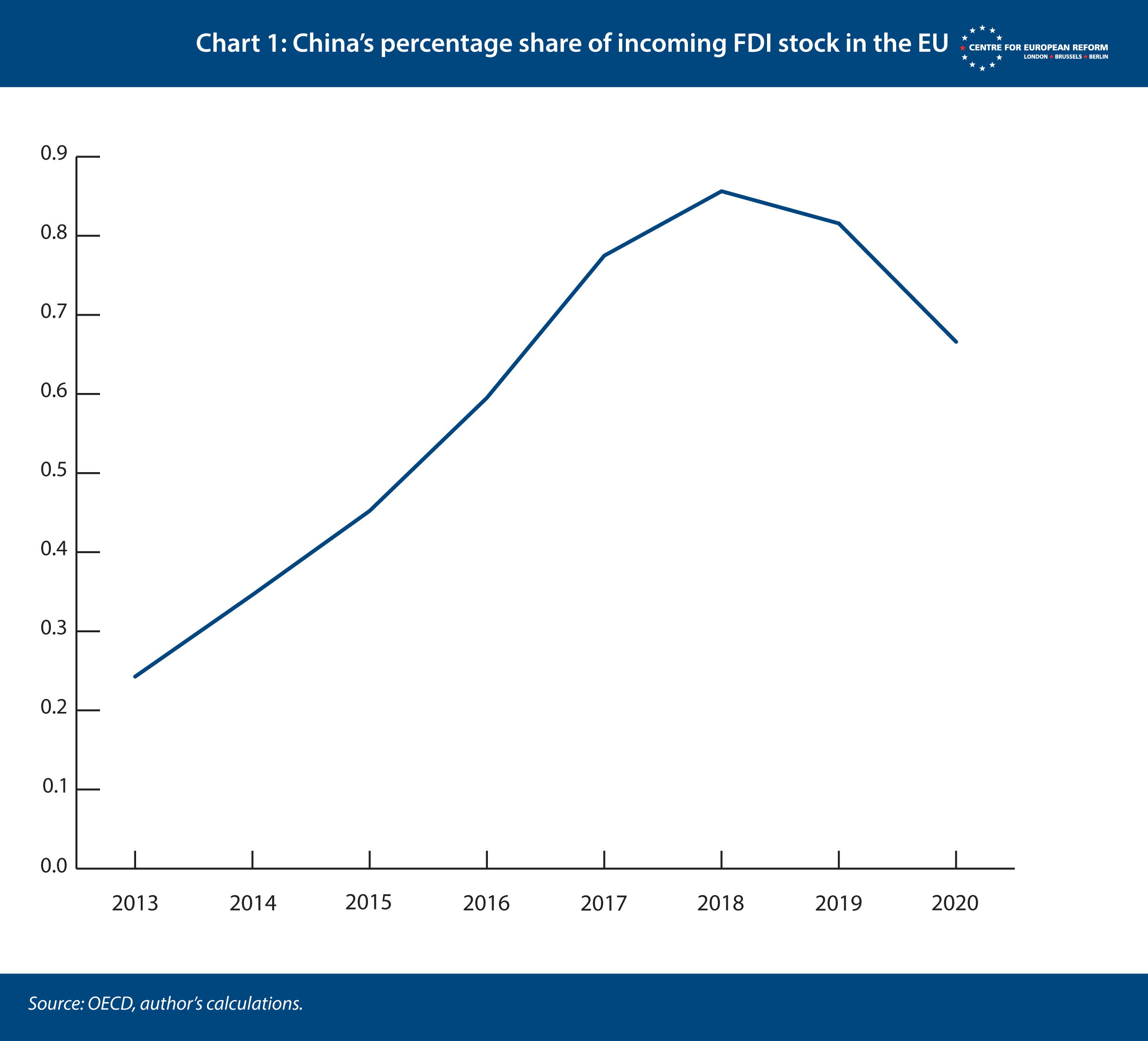

In that context, the EU worries that Chinese trade and investment in Europe will increase the EU’s dependencies, especially over strategic sectors. But these worries are not always evidence-driven. Take Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe. This comprises only a small proportion of overall FDI in EU member-states (even in Hungary, the most exposed EU country, only 3 per cent of incoming FDI stock is from China).4 And, as Chart 1 shows, China’s share of total FDI stocks in the EU has been in decline for some years. In part because EU member-states are now more proactive in assessing whether Chinese investment poses security risks, China’s inward FDI is increasingly focused on establishing new businesses and investing in start-ups, rather than investments which pose more immediate risk to Europe like buying up critical infrastructure.5

Even the fact that Chinese investment in or sales to Europe might result from apparently unfair advantages – such as state subsidies or a monopoly at home – is not necessarily of concern. For example, despite the estimated $248 billion China spent in 2019 on industrial policy,6 China has at best a mixed track record of creating globally successful export industries. Consider the proposed tie-up between two major EU rail firms, Siemens and Alstom, in 2019. The French and German governments lobbied the European Commission to wave the deal through the EU’s merger control laws, claiming the resulting ‘European champion’ would be Europe’s only hope to compete with the state-subsidised Chinese rail firm CRRC. However, the European Commission soberly concluded that CRRC was not a credible supplier in Europe – pointing to CRRC’s consistent failure to deliver in markets where it needed to compete on its merits.7 The Commission’s analysis appears to be borne out so far. A recent study which raised alarm about the $1.3 billion that CRRC received between 2015 and 2020 in state subsidies also acknowledged that “there is not clear evidence of an upward trend in CRRC’s penetration of foreign railroad rolling stock markets”.8 In other strategic sectors like semiconductors, Beijing’s subsidies have also fallen well short of their objectives.9 This is unsurprising. Firms that have to succeed on their own merits are often more innovative and competitive than those that rely on subsidies. Take America’s digital giants: they have become globally dominant thanks to a large US domestic market and the availability of long-term capital, not through state support.

When foreign firms have apparently unfair advantages, this harms Europe’s internal market only in a few cases – most of which can be addressed to some extent by EU laws already. A key example is where markets are susceptible to a ‘winner takes all’ outcome – so a foreign firm (or firms from a particular country) can permanently squeeze out competitors, making Europe dependent on that firm, and ultimately facilitating anti-competitive conduct or giving foreign countries political leverage over the EU. But only a few markets are susceptible to these outcomes.10 These include high-tech and capital-intensive markets which benefit greatly from economies of scale: once a leader emerges, it may become difficult for anyone else to catch up. This explains why the US and the EU have granted huge subsidies to their own aircraft manufacturers, which has allowed both Boeing and Airbus to remain in competition (though at the cost of making it harder for potential challengers, who may have innovated to create cheaper, faster, safer or greener flights). Similarly, Taiwan’s aggressive subsidies for its semiconductor manufacturers have led even well-resourced rivals like Intel and Samsung to fall behind, and are only now spurring the EU and US to subsidise domestic production which may help improve competition.

The EU’s level playing field instruments need to target the right problem: whether a foreign firm’s ‘unfair’ advantages will damage the EU internal market or create undesirable dependencies.

EU competition policy can already address the risk of subsidies undermining competition without compromising the openness of the EU’s market – so there is not a large gap that the level playing field instruments need to fill. For example, when considering whether to allow a foreign company to buy an EU firm, competition authorities may consider whether the combined firm would have advantages like access to foreign subsidies that would undermine competition. These advantages could include access to a foreign government’s subsidies, or having a protected monopoly abroad.11 The European Commission also may also treat all Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as one ‘undertaking’ when applying merger control law. This means that when a Chinese SOE attempts to acquire a European firm, Brussels can always treat the deal as important enough to warrant review by the European Commission – as opposed to being a smaller deal which can be reviewed by a national competition authority.12 The same approach could plausibly be extended to all large Chinese firms if there is evidence they are not genuinely competing with each other.13

The EU has other targeted tools which help too. FDI screening allows governments to ban foreign investments which would risk security or public order, such as takeovers of firms in strategically important industries. Many EU member-states have also adopted rules for sensitive sectors, for example to limit the involvement of Chinese ‘national champions’ in rolling out EU communications networks. The EU has also increased its use of WTO-based ‘trade defence instruments’ (TDIs) against China, which can counteract the effect of subsidies or the ’dumping’ of imports into the EU at unfairly low prices, which harms domestic producers.

These tools have some gaps and weaknesses which the EU’s level playing field measures can fill. For example, competition law generally cannot prevent a foreign firm using unfair advantages to become dominant (as long as it does not grow by acquiring other companies): competition authorities can only intervene once the company abuses its dominant position. Only a few sectors like telecommunications have regulations which actively promote competition so abuse cannot occur in the first place. Competition authorities have also complained that it is hard to make evidence-based decisions about how China’s subsidy policy may play out.14 Finally, competition authorities also generally lack powers to intervene in public procurement decisions, even though the award of large government contracts can often have huge impacts on the market. Similarly, the EU’s FDI screening mechanism only addresses security risks associated with investment, rather than monitoring foreign firms’ market strengths or the way they export to Europe, which is not a wholly satisfactory way to improve Europe’s economic resilience. TDIs have significant shortcomings too. For example, the EU is only willing to use them in ways allowed by international trade law. That means the EU cannot use them to target subsidies for services firms or indirect subsidies such as cheap financing.

The EU’s level playing field instruments should therefore help plug these gaps in existing EU law. Instead, they tend to start from the expansive position that certain types of advantages enjoyed by foreign firms are inherently ‘unfair’. ‘Unfairness’ is not an especially helpful concept and it does not target the right problem: whether the foreign firm’s advantages will damage the EU internal market or create undesirable dependencies.

For example, the EU could only use the Foreign Subsidies Regulation when it suspects a foreign subsidy could “potentially negatively affect competition”.15 However, that is an undemanding threshold. A negative effect on competition only needs to be a potential, it does not need to be likely or material. That is a much lower standard than required by competition law, for example. The FSR could prevent firms from investing in the EU’s single market, even if they offer the best value for money for European consumers and would probably not materially increase the EU’s dependencies.

The International Procurement Instrument similarly risks being insufficiently focused on the need to develop competition. It allows the Commission to restrict foreign firms from participating in EU public procurement, based primarily on whether EU firms have a fair chance to bid for public contracts in that foreign firm’s country of origin. However, the IPI discourages the Commission from taking harsh action if there are limited alternatives to the firms who would be excluded. This provision is intended to “avoid or minimise a significant negative impact” on public authorities running a procurement process.16 However, this discourages the Commission from acting in precisely the types of situation where the EU most urgently needs to encourage the emergence of alternative suppliers.

The EU should not simply assume that when China deploys ‘unfair advantages’ it will achieve the outcomes it wants. Open and competitive markets deliver more economic growth and resilience in the long run.

If foreign countries subsidise goods or services for European customers, the EU should proceed carefully – it should be wary of increasing its dependence on countries which are systemic rivals, but it should not necessarily immediately raise market barriers to negate the benefits. The EU should not simply assume that when China deploys these ‘unfair advantages’ it will achieve the outcomes it wants – and the EU should have conviction that its commitment to open and competitive markets will deliver more economic growth and resilience in the long run. The FSR, IPI and other level playing field measures could still be useful when they address specific problems which EU laws do not currently address well, or where they address broader global problems like carbon emissions. But when the EU is merely trying to protect its own firms, it needs to act with discretion and care, so it does not weaken the EU internal market by prohibiting useful FDI and reducing competition.

Do the level playing field instruments raise the cost of doing business in the EU?

The level playing field instruments could also harm the EU internal market by raising the cost of doing business in Europe. If the instruments merely imposed costs on Chinese firms, that might pose little concern. After all, China has a relatively low share of total FDI in Europe, and Chinese FDI does not necessarily bring better management, know-how or technology to Europe than FDI from elsewhere. However, because the instruments are on their face non-discriminatory, firms from any non-EU country – even if the firm ultimately poses no risk – will have to accept greater costs, administrative hurdles, delays and uncertainty.

In some cases, the burdens will be relatively targeted. For example, the International Procurement Instrument is designed so that the Commission needs to decide to apply it to a particular third country with closed public procurement markets. In choosing to do so, the Commission can choose to apply the IPI only to particular firms from that country. In this way, the IPI would not impose costs indiscriminately on all foreign firms seeking to participate in EU public tenders.

However, the Foreign Subsidies Regulation is not as targeted. For example, it would require many large firms to provide a notification when they are involved in a large merger or acquisition of an EU company, or when they participate in a large EU public procurement bid, and have received foreign subsidies in the previous three years. Even a large firm which receives no foreign subsidies will have to make a declaration to that effect before it participates in EU public procurement processes. The Commission’s definition of ‘subsidy’ is deliberately broad, to avoid circumvention – it includes tax exemptions and payments for goods and services, for example. That means, however, that vast numbers of firms will need to investigate all possible sources of funding or financial advantages they receive from foreign governments, making participation in EU public procurement processes and corporate merger and acquisition activity far more burdensome than it is today. The EU should revise the FSR so that it needs to be ‘activated’ for a particular country, in the same way as the IPI, so that foreign firms operating in the EU do not all face onerous costs of identifying and declaring foreign subsidies which pose little risk to the EU’s single market.

The compliance burden is higher still with some other level playing field instruments. For example, the CBAM addresses iron and steel, cement, fertiliser, aluminium and electricity: these are carbon-intensive goods most exposed to carbon leakage. These industries carry higher risks of EU producers moving their production abroad to benefit from lax environmental regulation. Importers of these goods to the EU will be required to calculate the embedded carbon in a given product, which will be certified by accredited experts, and buy an appropriate number of carbon certificates: the mechanism will involve both administrative procedures and financial payments. Given the large costs this will impose on firms importing into the EU, there is a good rationale for exempting the least developed countries from the CBAM,17 and supporting small firms who will not be well equipped to comply with the CBAM.

The EU has a steadily shrinking share of global GDP, and its efforts to complete the single market – by increasing harmonisation to lower the costs to businesses, in turn increasing investment and competition – have stuttered in recent years. Growth has also stalled. Given these persistent problems, the EU needs to be cautious about increasing costs and regulatory risks for firms operating in its internal market. If it does not, foreign firms might choose to expand elsewhere, harming competition in Europe and creating less investment.

How can the EU can use its level playing field tools to open up foreign markets?

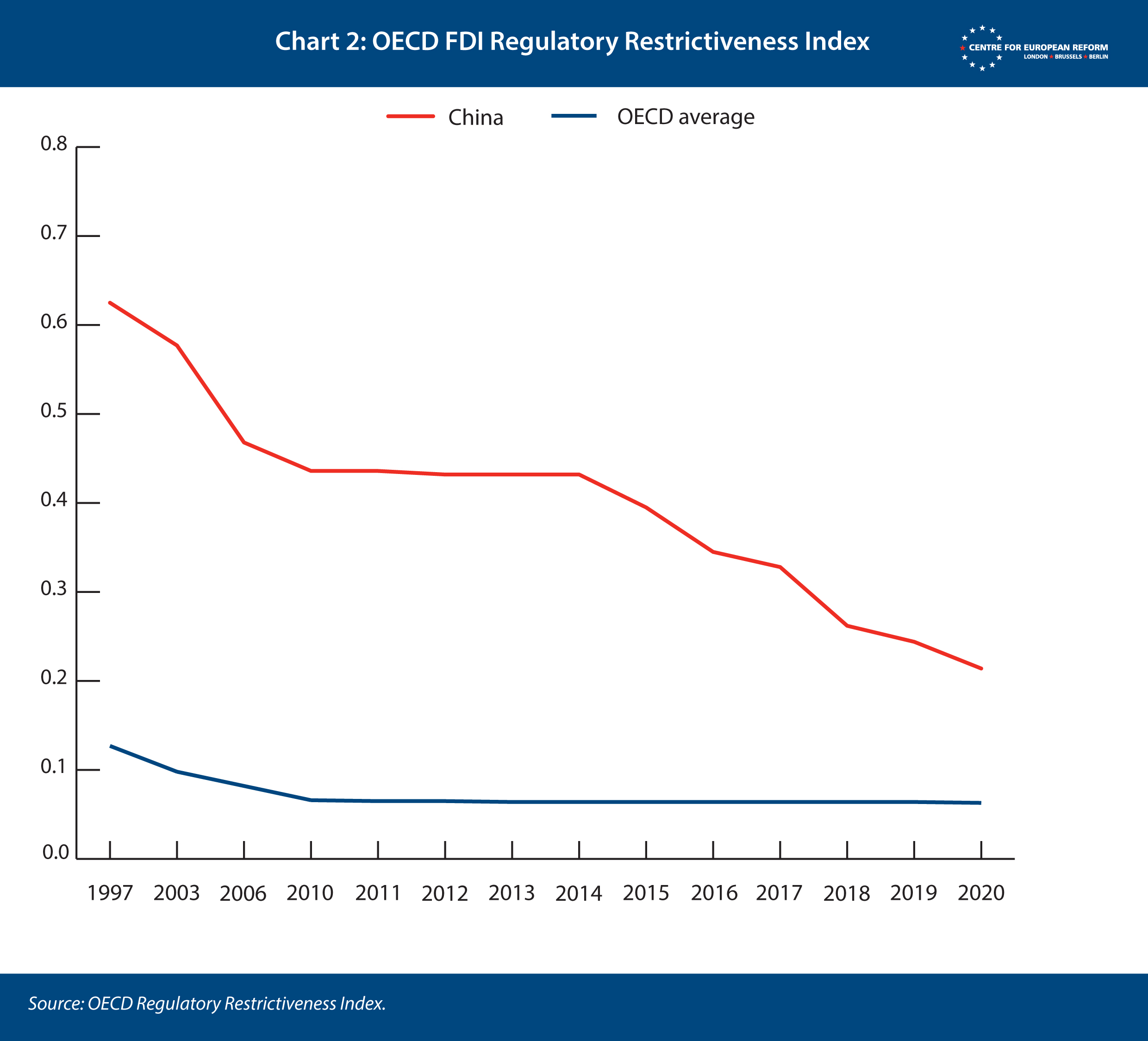

Europe’s level playing field measures were not always geared towards protectionism. Initially, the EU came up with laws like the IPI to help European firms find new growth opportunities in hitherto closed foreign markets like China’s. As Chart 2 shows, China has progressively opened up many sectors of its economy for foreign investment, at least on paper,18 even if they remain more closed than the average of OECD countries. European businesses have assumed that as China’s population becomes wealthier, and if these market restrictions could be addressed, then demand for European products would probably grow.

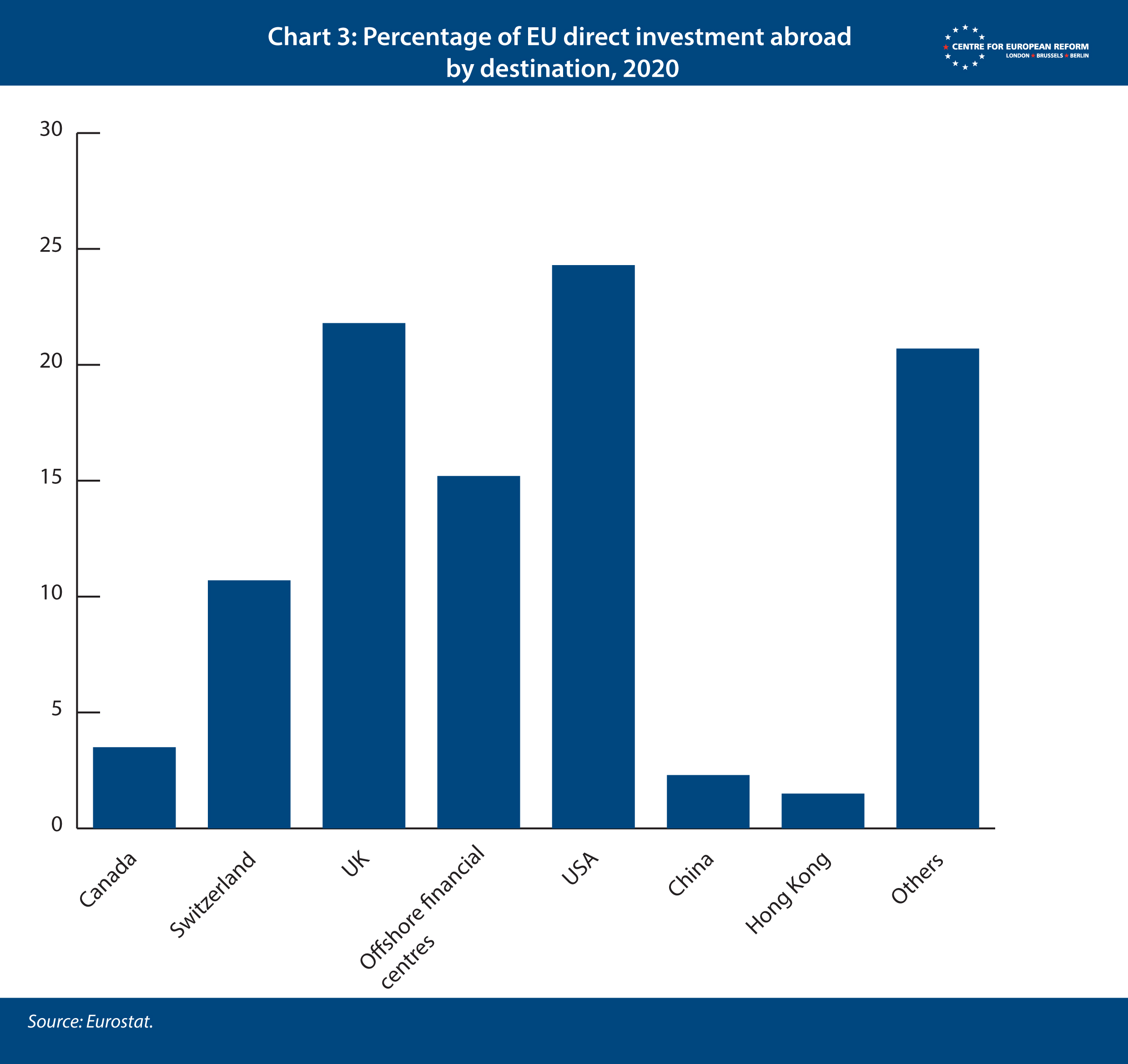

However, the EU’s frustrations with China persist. Chart 3 indicates that Europeans’ appetite or ability to invest in China remains limited compared to investment in Western economies. Investment in China represents only a small proportion of the EU’s total outward FDI, far smaller than China’s share of the global economy, and has not increased by much in recent years.

But as the EU now faces the need to diversify its trade and investment with countries that pose less political risk, ongoing bugbears with countries like India and the US – which both have protectionist tendencies – have now become far more relevant. It was Biden’s recent changes to the Buy American Act, rather than any changes to China’s policies, which finally convinced EU member-states to adopt the International Procurement Instrument about a decade after it was first proposed. And the US is heavily subsidising industries like domestically assembled electric vehicles and semiconductor manufacturing.

This explains one potential attraction of the level playing field instruments: they would be incredibly valuable to the EU if they could be used as a ‘bargaining tool’ to negotiate greater access to foreign markets for EU firms. If they convince foreign countries to open up their markets (or adopt similar measures like carbon pricing), the EU will benefit, without having to restrict access to the EU internal market or imposing new costs on importers. But to achieve this, the level playing field tools need to be flexible, targeted and strategic. That way, the EU can use them in situations where they have most chance of making a difference, and where they would serve the EU’s strategic goals of diversifying its supply chains.

The EU’s instruments are designed to look legalistic, country-neutral and inflexible.19 In part, that may help de-escalate international tensions, while giving the Commission more leverage in international negotiations: the Commission can simply claim it is enforcing EU law and that its hands are tied. In practice, however, the level playing field instruments are often more discretionary than they look. Under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, for instance, the Commission can decide which foreign subsidies to investigate. If it finds that the subsidy potentially distorts competition, the Commission can still decide that its negative effects are outweighed by “other positive effects of the foreign subsidy such as broader positive effects in relation to the relevant policy objectives”.20 This flexibility gives the Commission the tools to choose where to intervene, and many ways to avoid politically inconvenient or strategically unwise decisions. The International Procurement Instrument provides similar flexibility: for example, the Commission can take into account whether an investigation would be “in the interest of the Union” before considering taking action. Even the CBAM – which imposes ‘automatic’ disadvantages on certain foreign firms – applies to a small number of carbon-intensive products, such as steel and aluminium. The EU already knows which countries this will most affect, so this is not a tool with particularly unpredictable direct consequences.21

The EU needs to be aware of two risks, however.

First, some of the instruments have a degree of inflexibility once they are activated. This may give the EU very little room to compromise and take other countries’ concerns into account:

- The FSR gives the Commission discretion to weigh competing factors in deciding whether a subsidy requires redress. However, once it finds that redress is required, its hands are firmly tied. The Commission cannot accept partial concessions; it is only allowed to accept solutions which “fully and effectively remedy the distortion”.22 The Commission should have more discretion to accept politically feasible compromises, rather than insisting that firms fully remedy the effects of foreign subsidies they have received.

- The CBAM is even less flexible. It essentially forces foreign producers to pay carbon prices, without (for example) applying any special treatment to poorer countries. This lack of flexibility is by design: international trade law limits the EU’s ability to discriminate when applying tariffs on goods. However, the EU could still consider making the measure more targeted – for example, by excluding less-developed countries.

Reducing the Commission’s space to agree a negotiated outcome may be a useful bargaining tactic in some cases, but in many cases it simply removes the scope for pragmatic compromise. The risks other countries seeing the EU as trying to dictate their sovereign policy choices, which will increase the risks of retaliation.

Second, the instruments remain legal in nature – and their use is ultimately supervised by the European Court of Justice (ECJ), which must apply the law apolitically. The ECJ may eventually interpret the instruments in ways that tie the Commission’s hands in unexpected ways. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides a telling example. The ECJ has twice struck down arrangements the EU had made to allow free data flows with the US, despite the US making significant compromises to give special protection to EU nationals’ data. The inability to resolve this problem imposes significant costs on EU and US firms, yet the EU is unwilling to amend the GDPR and legislative gridlock in Washington constrains America’s ability to give Europeans more protection. The EU’s level playing field instruments carry a similar risk. The Commission may use them (or decide not to use them) in ways that are politically expedient – but the Commission’s decisions could be challenged before the ECJ and could be over-ruled. That might lead to significant economic and political costs for the EU, leaving the EU and its foreign partners in a stalemate. The EU must be restrained in its use of the measures, to minimise the risk of similar situations.

Conclusion

The EU has a challenging task of re-orienting its trade and investment strategy so that it can better cope with growing rivalry between China and the West. To do so, the EU needs to focus on strengthening its own internal market and prioritising trade and investment with countries which pose less political risk than China. International agreements will remain essential – and can tackle problems like carbon emissions and ‘national champions’ which the EU’s level playing field instruments can never fully solve. But the EU’s level playing field measures could give Europe more negotiating leverage with its partners. In using these tools, the EU must remember that its strength remains its market openness. It should focus on growing opportunities for Europe rather than protecting European businesses at home.

The EU’s level playing field instruments will still have some risk of reducing competition and investment in Europe and in some cases may give the Commission too little scope to make pragmatic political compromises. The EU’s bet is that the long-term gains justify those risks. That bet may pay off, if the EU deploys these tools shrewdly.

2: Ian Bond, François Godement, Hanns Maull and Volker Stanzel, ‘Europe needs a China strategy’, CER bulletin article, Issue 144, June/July 2022.

3: John Springford, ‘The US could cope with deglobalisation. Europe couldn’t’, CER bulletin article, Issue 145, August/September 2022.

4: Sam Lowe, ‘EU efforts to level the playing field are not risk-free’, CER insight, July 16th 2020. Note that the IPI and CBAM could also target firms which operate outside the EU without FDI in the EU.

5: Agatha Kratz, Max J. Zenglein, Gregor Sebastian and Mark Witzke, ‘Chinese FDI in Europe: 2021 Update’, MERICS report, April 27th 2022.

6: Gerard DiPippo, Ilaria Mazzocco, and Scott Kennedy, ‘Red Ink: estimating Chinese industrial policy spending in comparative perspective’, Center for Strategic & International Studies report, May 2022.

7: European Commission, DG Competition, ‘Case M.8677 – Decision’, February 6th 2019, paragraph 274.

8: Oxford Economics, ‘Off Track: The role of China’s CRRC in the global railcar market’, July 2022, page 5.

9: Shunsuke Tabeta, ‘‘Made in China’ chip drive falls far short of 70% self-sufficiency’, Nikkei Asia, October 13th 2021.

10: Agatha Kratz and Janka Ortel, ‘Home advantage: How China’s protected market threatens Europe’s economic power’, ECFR policy brief, April 15th 2021.

11: Examples include the Alstom/Siemens case and CRRC’s acquisition of Vossloh: see Bundeskartellamt, ‘Case Summary - B4-115/19’, April 27th 2020. Notably, however, the German authority emphasised the lack of available information about subsidies, which is a problem the FSR may help address.

12: European Commission, DG Competition, ‘Case M.7850 – Decision’, March 10th 2016.

13: Nicolas Petit, ‘Chinese state capitalism and Western antitrust policy’, Concurrences Review Number 4-2016, June 21st 2016.

14: See Bundeskartellamt, ‘Case Summary - B4-115/19’, April 27th 2020.

15: FSR art 3(1). References to the FSR are to the July 11th 2022 provisional agreement resulting from negotiations between the EU law-making institutions.

16: IPI article 6(3). References to the IPI are to the version passed by the European Parliament on June 9th 2022.

17: Sam Lowe, ‘The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism: How to make it work for developing countries’, CER insight, April 22nd 2021.

18: The OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (FDI Index) measures statutory restrictions on FDI in 22 economic sectors, in particular focusing on foreign equity limitations; screening mechanisms; restrictions on employment of foreigners; and operational restrictions. In practice many constraints on foreign investment remain.

19: Grzegorz Stec, ‘Technocratic Mitigation – The European way of managing the China challenge’, RUSI, July 6th 2021.

20: FSR article 5(1).

21: Elisabetta Cornago and Sam Lowe, ‘Avoiding the pitfalls of an EU carbon border adjustment mechanism’, CER insight, July 5th 2021.

22: FSR article 6(2).

Zach Meyers is a senior research fellow the Centre for European Reform.

September 2022

View press release

Download full publication