Russia-Ukraine: The West needs a sanctions strategy

- The West’s unprecedented sanctions against Russia are warranted. But after the initial flurry of sanctions, Western leaders now need to take a more strategic approach.

- Sanctions do not all do the same things. Some are signals, either as a warning to another state, or to prove to a domestic audience that the government is ‘doing something’; others aim to coerce countries to change course; and others serve to constrain a country’s capabilities to engage in deplorable behaviour in future.

- The West should have used signalling sanctions well before Russian forces crossed the Ukrainian border, to deter military action. The West failed even to have co-ordinated signalling sanctions ready to go as soon as Russian troops entered Ukraine.

- Having been slow to impose signalling sanctions, Western countries and institutions moved very quickly after the attack to impose far-reaching coercive sanctions, including freezing the Central Bank of Russia’s access to most of its foreign exchange reserves. But coercive sanctions are unlikely to work against a government willing to see its population suffer and able to repress any popular dissent. They will also lose some of their effectiveness over time.

- The EU has started to impose constraining sanctions, such as limits on technology exports to Russia. These will probably need to be in place for the long term, with the aim of eroding Russia’s industrial base; suppressing its capabilities; and thwarting its economic ambitions so it poses less of a threat in future. Western governments must be clear that constraining sanctions serve an important purpose, even if their effects are not immediately obvious.

- Finally, much Western action in recent days – such as measures to crack down on illicit finance and disinformation – should not be considered part of the sanctions targeted at Russia. Instead, they ought to become ‘business as usual’ to protect the West’s vital interests, no matter the outcome in Ukraine.

- Having failed to dissuade Putin, the tough sanctions that the West has now imposed on Russia and the likely countermeasures will seriously damage Western economies as well as Russia’s. It would be foolish for Western leaders to assume that Putin would never cut off gas supplies, which would seriously impact Europe’s economy. Russia may also be in a position to drive up global food prices. It could also make the current shortage of computer chips worse, an issue the EU’s industrial strategy should focus on.

- The West needs to keep communicating to those Russians who may still be able or willing to hear its message that sanctions may be withdrawn based on how Russia behaves. Putin wants to tell Russians that whatever they do the world will harm them; the West needs to say that there is a way back to normal relations.

Putin’s latest invasion of Ukraine prompted immediate political condemnation from Western leaders. With unprecedented speed, the EU, US and UK have instituted a comprehensive set of economic sanctions – treating Russia in a comparable way to pariah states like North Korea.

A flurry of new sanctions has been announced in each of the past few days. The initial sanctions banned major Russian banks from Western financial systems; excluded many Russian entities from raising money on EU, UK and US capital markets; froze assets and limited Western banking access for certain Russian nationals; and banned exports of various high-tech goods to Russia. That was followed by the expulsion of some Russian banks from SWIFT, the interbank network which supports nearly all cross-border payments; direct sanctions on the Russian central bank, which froze its access to parts of its foreign reserves; and an EU-wide ban on Russian planes using member-states’ airspace.

The West has acted quickly and decisively. But Western leaders now need to take a more strategic approach.

In addition, under pressure from governments, shareholders or public opinion, many Western companies have ‘self-sanctioned’, intending to divest themselves of their Russian investments, suspend their operations in Russia or voluntarily cease trading with Russian firms. And many of the world’s largest container shipping companies have suspended deliveries to and from Russia, or limited them to food, medical equipment and humanitarian goods, steps which will have a significant impact on the Russian economy. Some Western ports are also refusing to unload Russian cargoes, even where government regulations would still allow them to. The US has announced a ban on Russian oil and gas imports; the UK plans to phase out imports of Russian oil and is exploring an end to imports of Russian gas. The EU, which is much more dependent on Russian energy resources than the UK or US, is also rapidly developing plans to limit imports of Russian fossil fuels – industries which contribute nearly half of the Kremlin’s budget revenue, but which the West was initially reluctant to sanction, given the immediate impacts on Western economies.1

In the initial phase, there has almost been a sense of competition: who has confiscated more oligarchs’ yachts? Who has forced more Russian banks to stop operations? The West has acted quickly and decisively. But Western leaders now need to take a more strategic approach.

Different measures are more effective in hitting different aspects of Russian political and economic activity, both domestic and external. Any sanctions that have a significant effect on the Russian economy are almost certain to have some effect on Western economies, which needs to be weighed up. In some cases, measures may paradoxically benefit parts of the Russian economy. For example, if measures targeting the Russian oil industry increase oil prices by more than they reduce Russian output, Russia may enjoy a windfall. If the West wants an oil embargo to have a negative impact on the Russian economy, rather than just signalling displeasure, then it needs to consider the extent to which other buyers will step in. But at present, traders are struggling to sell Russian oil on global markets, even at large discounts. An effective sanctions policy should also be based on a clear understanding of what each measure is designed to achieve and over what time frame; what public messages (for Russian and Western audiences) must accompany each measure; and what conditions would justify escalating or suspending sanctions.

The West needs to explain what further steps it may take as Russia’s behaviour deteriorates further, for example with increasingly widespread and indiscriminate targeting of civilian infrastructure, including nuclear power plants, and how it will respond to countermeasures. It should set out which sanctions would be suspended or withdrawn if Russia changes its behaviour. It must also be clear that certain policy changes, such as measures to crack down on illicit finance and disinformation, should not be treated as sanctions targeting Russia. Instead, they must represent the new ‘business as usual’.

What sanctions can – and cannot – do

Sanctions do not all do the same things. As the academic Francesco Giumelli has been explaining over the last decade, some sanctions are intended to signal (such as suspending sporting contacts) – and serve as a warning to the target country to change course, or a way for a government to respond to public pressure to ‘do something’; some are intended to coerce a change of behaviour (such as comprehensive economic sanctions of the kind imposed on Iraq after the 1990-1 Gulf War and on Iran in response to its nuclear programme); and some are intended to constrain a country’s economic or military development, to damage its capabilities (for example, restrictions on the export of technology).2 The categories may overlap: a measure intended as a short, sharp shock to coerce a change of policy may end up remaining in place as a constraining measure.

Each of the three types of sanctions can be useful in the right circumstances. But governments need to manage the expectations of their own populations and business communities: about how long it may take for some steps to have an impact, how long those steps might be in place for, and what the costs might be for their own economies. Governments also need to understand the likelihood that some measures will become less effective over time, either because targets will find ways to circumvent them, or because they will get used to them and adapt. Western policy-makers need to ensure that targets interpret sanctions correctly. Putin could portray sanctions that hit the general population in Russia as proof that the West is determined to harm Russia. The West must convey a clear message to those in Russia able and willing to listen, that sanctions are a direct response to Putin’s violations of international law and norms in invading Ukraine and will last only as long as those violations continue.

First phase sanctions: Signalling and coercion

In an ideal world, the West would have used signalling sanctions well before Russian forces crossed the Ukrainian border, to deter military action. Financial pressure on wealthy members of the Russian elite, for example, could have encouraged them to put pressure on Putin to de-escalate. Some of the richest 'oligarchs' who made their money in the 1990s before Putin came to power, have little political influence. Some of the former KGB officers who are closest to Putin, however, have also become very wealthy; they and their families (some of whom live in the West) have a lot to lose from Western sanctions. At the very least, the West should have had co-ordinated signalling sanctions and had them ready to go into force as soon as Russian troops crossed the Ukrainian border, which might have persuaded Putin to settle for less, on the basis that a full-scale invasion would be too costly. The opportunity was missed. This may have been because leaders of the largest Western countries did not believe – and did not want to believe – that Putin would attack Ukraine. Others were initially more concerned with protecting their economies.

The West moved quickly to impose far-reaching coercive sanctions, intended to have immediate ‘shock and awe’ effects.

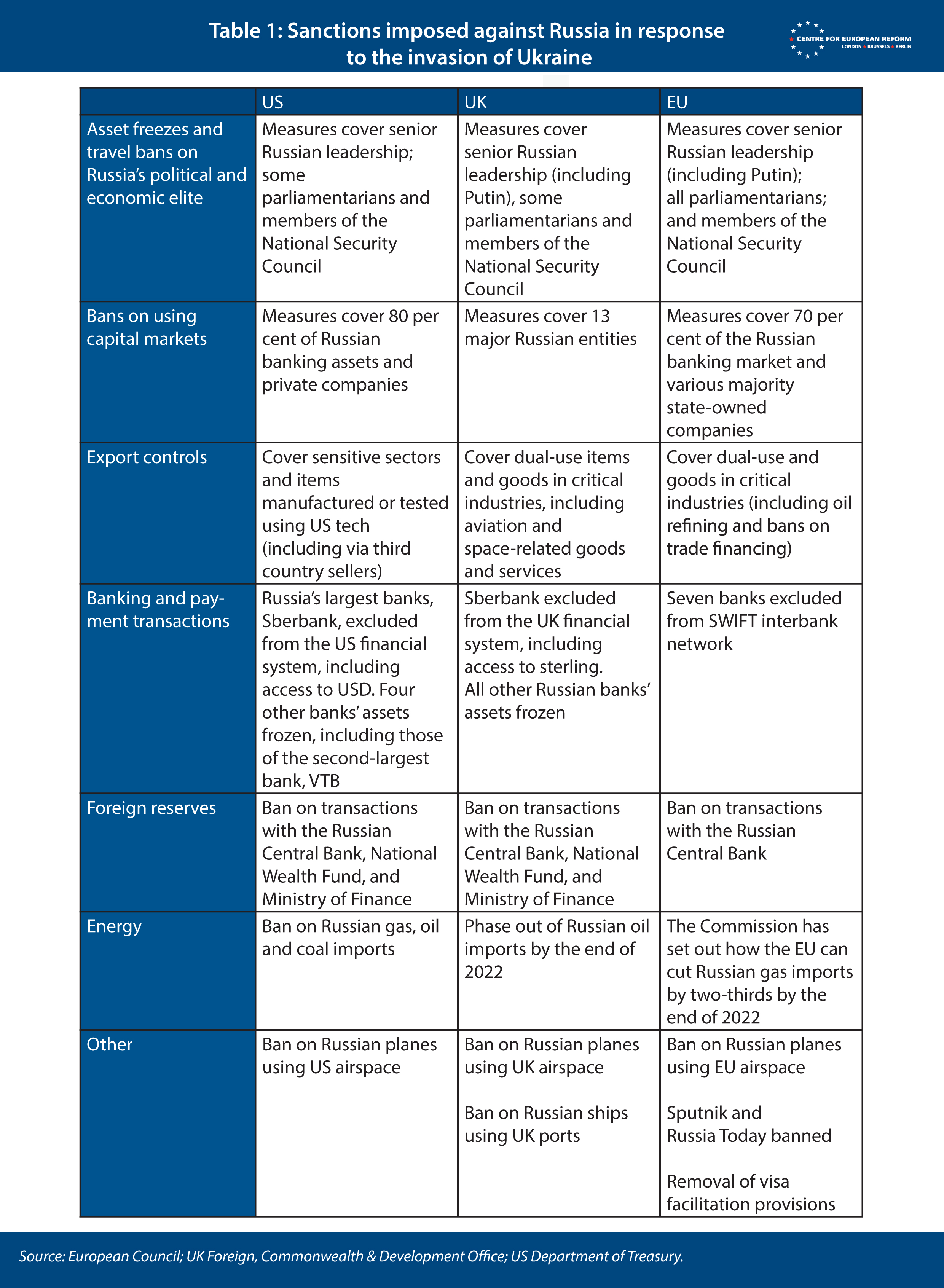

As a result, more than a week after the assault began, some Western countries, including the UK, had still not imposed comprehensive signalling sanctions, such as visa bans and asset freezes on all the members of the Russian parliament who voted in favour of recognising the independence of the Russian-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk ‘People’s Republics’. By contrast, the EU imposed sanctions on 351 Russian parliamentarians immediately after the vote. Signalling sanctions continue to appear piecemeal – including the decision by the International Paralympic Committee to ban Russian and Belarusian athletes from the Winter Paralympic Games, one day before they were due to open in Beijing.

Having been slow to impose signalling sanctions, however, Western countries and institutions moved very quickly after the attack to impose far-reaching coercive sanctions, intended to have immediate ‘shock and awe’ effects. The West is hardly pulling its punches. The UK and US have both excluded major Russian banks from their domestic financial systems, preventing those banks from using sterling and the US dollar. These measures will constrain Russia’s trade with the UK and US because cross-border transfers must normally pass through a chain of intermediary ‘correspondent banks’ and domestic central bank transfer systems. The measures will also harm Russia’s trade with many other countries, since the majority of international trade is in US dollars and all US dollar denominated payments will rely on a US bank at one point in the transfer chain.

The UK and US maintained broad sectoral exceptions, at least initially, for example in energy and agricultural goods – even though these are very significant sources of foreign revenue for Russia – to mitigate their impact on other countries. The EU has been even more cautious about the consequences of blanket restrictions on trade with Russia. For example, as Table 1 shows, the EU has gone as far – and in some cases further – than the US and UK in most sanction areas, including immediately sanctioning all members of the Russian parliament. But it has adopted weaker restrictions on cross-border payment transactions which impact international trade. The EU also continues to allow gas and oil imports, which the US will now ban.

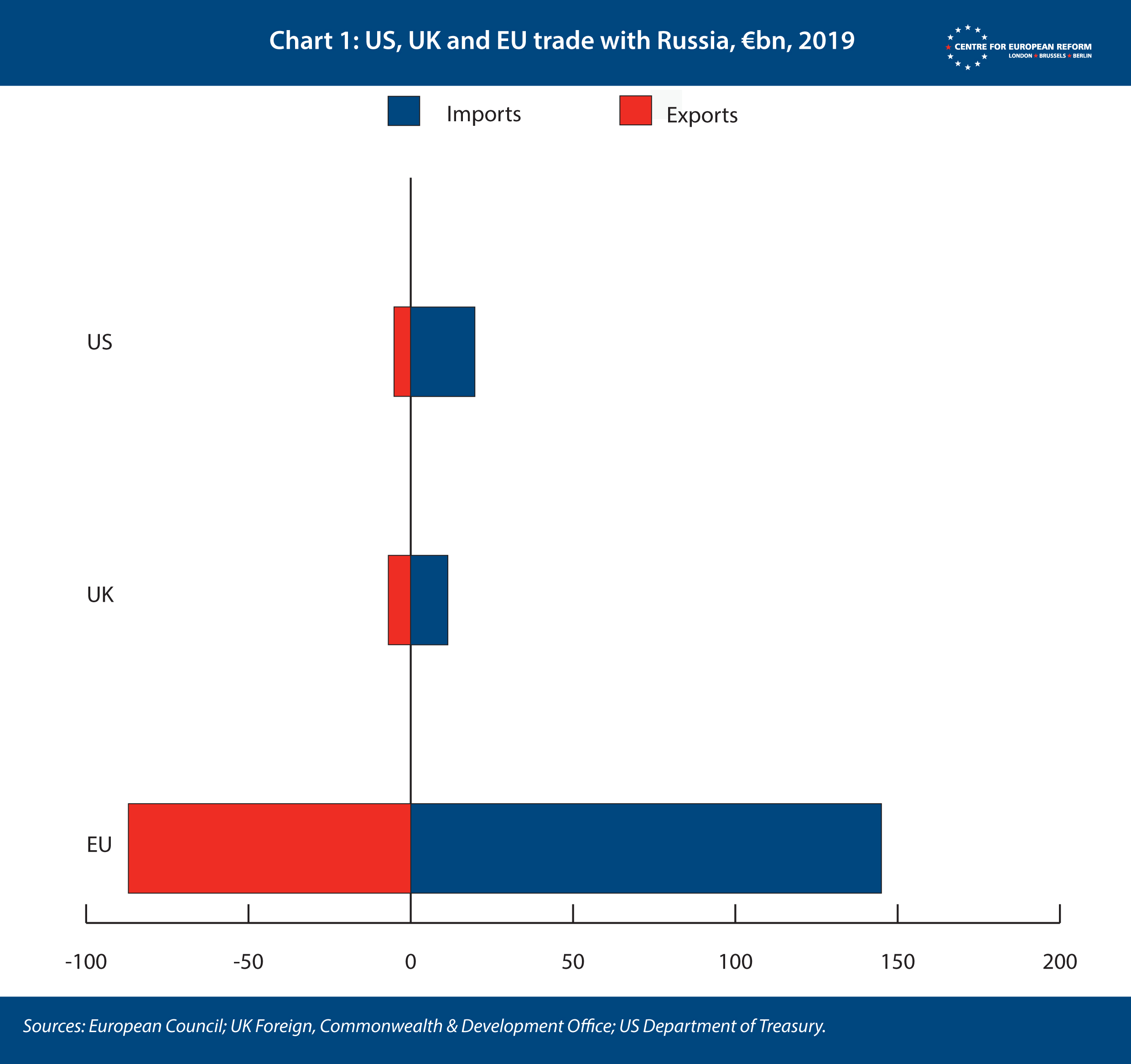

Thus, while the EU excluded a number of banks from SWIFT, those banks were carefully selected to minimise disruption to Russia-EU trade in key areas. And, unlike the UK and US, the EU has not forced European banks to break their correspondent banking ties with Russian banks – ties which are essential for cross-border payments including for international trade. Nor has it prevented Russian banks from dealing in euros. The EU’s caution is unsurprising: as Chart 1 shows, the EU is far more exposed to trade with Russia than the US or UK.

What is common to all of the EU, UK and US coercive sanctions is that they are intended to cause immediate disruption, but their effectiveness will diminish over time. One example is that US and EU sanctions only apply to certain Russian banks: where trade is still permitted, that trade could eventually be routed through non-sanctioned banks. That will probably require Russian and overseas banks to set up new correspondent banking relationships. These relationships require significant trust between the banks involved and for each bank to undertake due diligence on the other; globally, the number of correspondent banks has been declining for years because of the risks involved. Russian banks will find it particularly difficult to prove their trustworthiness while the Russian economic situation – and the liquidity of Russian banks – remains uncertain. But when the immediate dust begins to clear, at least a few new arrangements may emerge to mitigate the damage.

Alternatively, Russia can over time accelerate its reorientation towards China, to help soften the blow of sanctions. Large Chinese banks have seemed reticent to step in and support Russian financial institutions for now. They are wary of falling foul of US sanctions and thereby being cut off from the US dollar, which is far more important to them than profiting from trade with Russia. China’s trade with Russia, while growing significantly year-on-year, was worth only $110 billion in 2019; its trade with the US alone was worth $541 billion, and sanctions would hit China’s trade with many other countries too.3 Similarly, Chinese firms are not demonstratively closing their Russian businesses like Western firms. But, more quietly, some Chinese firms such as smartphone manufacturers have reportedly stopped exporting to Russia, probably due to a combination of fear of breaching existing sanctions; the risk of being targeted by additional Western sanctions in future; and an unwillingness to take on the business risks of trading with Russia, in particular exchange rate risks caused by the rouble’s precipitous decline in value. However, over time China will probably find ways to help. It could set up financial institutions intended specifically to facilitate trade with Russia, or connect Russian and Chinese banks using each of their domestic payment systems, thus facilitating cross-border trade and finance beyond the purview of the US. But when Russia turned to China in 2014, looking for an alternative to European markets for its gas, Beijing drove a hard bargain. This time also, it will probably expect Russia to provide benefits in return for helping it out of a tough spot, which will probably entrench Russia’s isolation from the West.

If coercive sanctions do not work, constraining sanctions will need to be in place for the long term.

The other risk is that unity among those countries implementing sanctions starts to fail. If Western governments want to preserve long-term and widespread international support for coercive sanctions, they will need to maintain broad public support for them in their own countries, even though both Western sanctions and Russian countermeasures are bound to have negative impacts on their own economies, as well as on Russia’s. To date, public support has been robust – as illustrated by the demonstrations taking place in European capitals in recent days – but this support may wither as energy and food prices increase, and if governments seek to fund increased defence expenditure with cuts elsewhere. Governments will also need to think about how they can mitigate the knock-on effects on third countries – for example, those in the South Caucasus and Central Asia whose economies depend heavily on remittances from migrant workers in Russia. If Western sanctions push the Russian economy into recession (as they are likely to), countries like Armenia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan will be particularly hard hit.

In general, coercive sanctions are less likely to work than signalling or constraining sanctions, particularly against a government willing to see its population suffer and able to repress any popular dissent. Russia’s decisions to effectively drive out Western news outlets and end access to close and social media platforms is therefore an ominous sign – as is its recent instruction for Russian websites to use domestic hosting services and the .ru domain, which may be precursors to cutting Russian users off from the global internet. Furthermore, where coercive sanctions have forced countries – such as Iran – to the negotiating table, this required a preparedness to compromise on both sides. But it is unclear that any compromise could be acceptable to both Putin and the West. If Russia can survive the short term, then, the examples of Iran and North Korea show that economic isolation might not deliver long-term policy change – even if Russia remains permanently poorer than it might otherwise have been. Instead, coercive sanctions may encourage Russia to partner up with other pariah states and double down on its behaviour.

Second phase sanctions: Constraining Russia

If coercive sanctions do not work, constraining sanctions will need to be in place for the long term, as they were in the Cold War. Several of the Western sanctions complement those aimed at delivering short-term damage and disruption, and are designed to have a persistent effect if Putin does not withdraw from Ukraine. These sanctions aim to erode Russia’s industrial base; suppress its military and technological capabilities; and thwart its ambitions to diversify its economy away from selling primary materials – constraining its ability to pose a threat in future.

These measures include the ban on many Russian entities raising funds using Western capital markets, limiting their financing and growth prospects. They also include targeted export bans – for example, constraints on exporting technology in areas such as oil refining; aviation and space; defence and security; and cutting-edge technologies.

Some of these export sanctions will have short-term effects. For example, it is difficult to see how Russian aviation can continue beyond the very short term, now that Russian airlines cannot procure spare parts, maintenance or support services from their manufacturers, and given Russia’s significant reliance on foreign aviation technology. But most will gain more bite after time. For example, the US has also adopted a version of the sanctions it imposed against the Chinese technology firm Huawei. These sanctions ban US firms from selling prohibited items to Russia – but also preclude firms elsewhere from selling items to Russian buyers if those items were manufactured or tested with US-originating technology. Nearly all computer chips, for example, use US designs, manufacturing technology or testing processes at some point in their production process. Sanctions will also have broader and indirect long-term effects, for example by accelerating the ‘brain drain’ of young, skilled Russians.

The tech sanctions may seem inconsequential in the context of the broad excision of Russia from Western financial systems; self-sanctioning by tech companies such as Apple and Microsoft (despite EU and US sanctions providing exceptions for many consumer products and services); and the Kremlin’s decisions to ban the likes of Facebook and Twitter. Nor do tech sanctions hit a big target: Russia has no tech powerhouses the size of Huawei, for example – Huawei’s pre-sanctions annual revenues totalled $136 billion, whereas Russia’s largest tech firm, Yandex, has annual revenue of $3 billion (and in the light of Western sanctions and the Central Bank of Russia’s interest rates hike, it has already warned that it cannot pay its debts). Little of Russia’s tech production is exported. Russia’s semiconductor businesses were also doing poorly even before sanctions hit: just prior to the invasion, Russian state agencies were reportedly looking to reject Russian-built Elbrus processors and turn back to Intel.4

Russia will inevitably lobby against such sanctions, but it will also seek to enlist interest groups in the West on its side, especially once the initial flood of headlines about atrocities in Ukraine passes. Western businesses will be encouraged to think that they are missing out on business opportunities because of the intransigence of their governments. Russia will try to blur the difference between coercive and constraining sanctions, and get politicians to see the latter as failing (and therefore not worth keeping in place) because they have not produced changes in behaviour. Western governments therefore need to be clear that these sanctions serve an important long-term purpose: to degrade Russia’s industrial capabilities and its ability to threaten others, by isolating the Russian technology sector from Western supply chains. These sanctions are only meaningful if maintained for the long term: as the world moves away from fossil fuels, Russia will face constraints on developing a high-tech digital economy. In doing so, Russia’s long-term technological and military capabilities – and its consequent capacity to pose threats to the West over the longer term – should decline. Russia will be left nearly wholly reliant on financial and technological support from China, which will want to keep Russia in the position of a subjugated junior partner.

The new business as usual

Finally, large parts of the West’s actions in recent days should have already been ‘business as usual’ to protect the West’s vital interests. These actions should not be seen as targeted at Russia, nor should they be negotiable if sanctions are withdrawn. Instead, the crisis has simply forced governments to confront issues they had treated as insufficiently important; too difficult; or politically inconvenient.

Across Europe, concerns about Russian political influence have been systematically ignored for years.

For example, Western democracies have promised to crack down on illicit finance – that is, the flow of ‘dirty’ money obtained through corruption, nepotism, tax evasion or other crimes. Across Europe, concerns about Russian political influence have been systematically ignored for years. For example, the UK government took little action on the back of a critical 2020 House of Commons Intelligence and Security Committee report highlighting repeated attempts by Russian oligarchs to influence UK politics, and has repeatedly delayed legislation aimed at countering foreign influence.5 This must change. EU member-states have committed to limiting ‘golden passport’ schemes, by which wealthy Russians can buy EU citizenship. The UK has also ended its ‘golden visa’ scheme, which allowed more than 2000 wealthy Russians long-term residence in the UK and a fast track to citizenship, and the Home Office is reviewing visas previously issued. Western countries have also promised to identify and freeze assets of the Russian elite. These measures will need to include legal reforms to ensure the underlying owners of assets can be traced; the ability to force residents to reveal the sources of unexplained wealth; and stronger rules to ensure foreign dirty money is not used to undermine democracy, for example through political donations. Most importantly, they will require significant resources to be devoted to investigation, monitoring and enforcement, and the West needs to be quicker to identify violations or work-arounds and update its restrictive measures accordingly.

In addition, the West needs to take further steps to tackle disinformation online. Social media platforms have taken unprecedented steps to respond to disinformation in recent days. They have changed their algorithms so Russian disinformation is no longer proactively recommended to users; prevented Russian state media from using online platforms to advertise or earn revenue; and Twitter finally joined other major platforms in labelling Russian state-affiliated media. However, these steps seemed haphazard, inconsistent and late – and were strewn with errors such as the removal of legitimate news sources. Simply banning Russia Today and Sputnik will not solve the problem – and may make it worse, by undermining freedom of speech and helping Putin to portray the West as hypocrites. Instead, the era of platform self-regulation must be replaced with co-regulation. The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) is currently in its final stages – with trilogue negotiations between the European parliament, EU member-states and the European Commission to settle on the final form of the law – but the DSA’s main focus is on outright illegal content rather than disinformation. Hence, the DSA lacks teeth: it requires platforms to put processes in place to tackle disinformation, but in its current form it will not ensure disinformation is tackled immediately and consistently by all platforms. EU law-makers will probably need several more months to settle on the final form of the DSA. This should give law-makers the opportunity to hold online platforms more accountable for protecting Western democracy against state-sponsored disinformation.

Countermeasures

In thinking about their next steps, Western governments also need to be conscious that Russia will retaliate. In 2014, Putin responded to Western sanctions with a ban on imports of agricultural products and foodstuff from countries that had imposed restrictive measures on Russia. At the time, Russia imported about €12 billion a year of such goods from the EU; by 2017 this figure had fallen to about €6 billion.6 Russia’s counter-sanctions promoted import substitution (at the cost of an increase in food price inflation), but their impact on Western economies was reasonably limited.7 Putin has taken a much bigger risk in launching a full-scale war against Ukraine now, and the West should assume that he will also be willing to impose more far-reaching counter-sanctions, even if that increases the costs to the Russian economy.

The West should assume that Putin will impose far-reaching counter-sanctions even if that harms Russia’s economy.

The West is phasing out most energy imports from Russia, which is an essential step to constrain Russia’s leverage in future. But in the short term, energy imports remain an obvious area of possible countermeasures against the EU, which is far more dependent on Russian oil and gas than the UK and the US. In preparation for the invasion, Russia had already limited sales of gas to Europe on the spot market and had withdrawn gas from European storage facilities owned by Gazprom, to illustrate its power to cut supply. Russian deputy prime minister Alexander Novak has since explicitly threatened to cut off gas supplies to Europe. One recent analysis concluded that if Russia cut off production completely for three months, Gazprom would lose $20 billion – less than a quarter of its expected 2022 gross profit – but it would be impossible for the EU to replace this gas completely.8 Another suggested that with “improvisation and entrepreneurial spirit” and a 10-15 per cent cut in gas demand, the EU could survive a total cut-off of Russian supplies next winter.9 If Russia did cut off supplies, it would not be in its long-term interests. It could not easily sell that gas elsewhere without building new pipelines and other infrastructure for exports. And Europe’s transition away from Russian gas would be hastened: member-states’ resistance to the Commission’s strategy to cut the EU’s reliance on Russian gas by two-thirds over the next year would become irrelevant. Russia would also seriously damage its chances of becoming the main supplier of hydrogen to Europe in future. But in circumstances where Putin is doing so many things that defy economic rationality, it would be foolish for Western leaders to assume that Putin would not take the chance to cause immediate and severe harm to Europe’s economy. With Russia supplying more than 40 per cent of Europe’s gas (including more than half of Germany’s and nearly all of some eastern European member-states’), the effect would be very serious, though shared unequally. The EU is already acting to mitigate the impact if Russia cuts supplies. It is planning to accelerate sourcing of alternative gas sources (mainly via imports of liquefied natural gas), including via joint procurement to refill strategic gas reserves ahead of winter. It is also accelerating the roll-out of renewable energy installations. The EU also buys large amounts of oil and coal from Russia; these supplies could be replaced more easily than its gas, but with some short-term disruption and at higher prices than Russia charges for its oil and coal.

The EU’s industrial strategy focuses on diversifying supply chains to avoid excessive dependencies on particular countries, particularly those that pose significant geopolitical risks. However, the EU’s focus in recent years has been on Europe’s dependencies with China and on improving the EU’s position in high-tech services dominated by the US. Until the last moment before the invasion, some EU member-states were not serious about reducing Europe’s more fundamental dependence on Russian gas – best illustrated by Germany’s refusal to cancel the Nord Stream 2 pipeline until February 22nd 2022, when Russia recognised the independence of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (Russian-controlled entities on Ukrainian territory, created in 2014) in a prelude to the war. The EU needs not just its recently-announced strategy to remove Europe’s dependence on Russian gas voluntarily over a number of years, but also a strategy to cope with Putin immediately turning off the gas supply. This may require financial support – such as transfers or loans to cover the cost of containing price hikes in the short term and to fund the necessary investments to reduce gas demand and obtain alternative supplies. The beneficiaries may need to include some countries such as Germany which are normally among the EU’s largest contributors.

Almost until the invasion, some EU member-states were not serious about reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian gas.

Energy is not the only area in which Russia is an important player. It is the world’s largest exporter of fertiliser. Together with Belarus (the seventh largest exporter) it accounts for 20 per cent of global fertiliser exports. On March 4th, Russia’s trade and industry ministry ‘recommended’ that producers should stop all exports temporarily. If producers follow the recommendation (which they will), and if the suspension continues for some time, global agricultural production is likely to diminish – adding to the impact of Russia’s invasion on world agricultural markets. In 2020, Ukraine was the world’s second largest exporter of cereals and its sixth largest exporter of oil seeds, but even if crops can be sown and harvested this year, which is questionable, none of the country’s ports will be accessible to carriers. Russia is therefore in a position to drive up global food prices. Even if Europe can protect its own food supplies, it needs to help lower-income countries relying on agricultural and food imports, who would otherwise suffer.

Russia is also an important supplier of raw materials for high-tech industries such as semiconductors and aviation. For example, one Russian company, VSMPO-AVISMA, is the largest supplier of titanium components to Boeing and a substantial supplier to Airbus. Boeing has already announced that it has suspended its purchases of titanium from Russia; though it apparently has sufficient stocks to last for some time, it will eventually have to find alternative sources of supply. Similarly, Russia and Ukraine are also leading suppliers of various materials – such as neon, palladium, scandium and nickel – which are essential to semiconductor supply chains. Such vulnerabilities ought to lead to questions about the priority given to the EU’s vanity projects – such as spending billions in state aid to manufacture cutting-edge semiconductors within Europe, when the US is doing the same, or to promote European cloud computing services over the numerous cloud services available from the American tech giants. It would be more useful for Europe to increase the recycling of materials used in high-tech manufacturing (including semiconductors, batteries and solar panels) and to develop synthetic alternatives. That could help Europe increase its independence from Russia in a way which is innovative and which complements, rather than competes, with US plans.

Conclusion

The West does not want to go to war with Putin. Sanctions are therefore its most effective way of putting pressure on him – indeed, Putin has described them as “akin to a declaration of war”. Over recent weeks, Putin has ignored every Western attempt to offer him an ‘off-ramp’. So far, he is also ignoring the damage that Western sanctions have already done to the Russian economy, and the longer-term effects that they will have on the country’s economic development. As he has made clear in two long telephone conversations with French President Emmanuel Macron since the war began, he is entirely focused on the subjugation of Ukraine.

In these circumstances, the West needs to move from responding to the immediate emergency to crafting a policy for the foreseeable future based around sanctions that aim to coerce Russia in the short term but also constrain it over the long term. At the same time, the West will need to keep communicating to those Russians who may still be able or willing to hear its message that sanctions can be reversed under the right circumstances. Putin wants to tell Russians that whatever they do the world will harm them, so they should not worry about the negative consequences of the invasion; the West needs to show that there is a way back to normal relations and the lifting of sanctions if Russia withdraws from Ukrainian territory.

The West also needs to have an adaptable sanctions policy. Past experience of long-running sanctions regimes, such as those against Saddam Hussein in the 1990s and those against Iran before it agreed to limit its nuclear programme in 2015, show that countries find ways to circumvent them over time, and that sometimes the elite find ways to profit from them (for example, acquiring the assets of sanctioned firms, as Iran’s Revolutionary Guards did). The EU in particular needs to be quicker to identify sanctions violations or work-arounds and update its restrictive measures accordingly.

Finally, the West, and especially the EU, needs to consider the lessons of this conflict and the tension before the war started. Had the EU been less dependent on Russia for energy, it might have been more willing to sanction Russia earlier. EU industrial strategy has been too focused on creating giants to compete with the US, while not giving sufficient attention to more urgent and fundamental needs like energy security.

The tough sanctions that the West has now imposed on Russia and the likely countermeasures will seriously damage Western economies as well as Russia’s. Opportunities to minimise these costs existed but were missed. The West needs to learn from this mistake. A policy of diversifying supply chains and avoiding excessive vulnerabilities is not economically irrational: it simply reflects the fact that short-term business incentives to source all imports at the cheapest possible price must be balanced against long-term political risks.

2: Francesco Giumelli, ‘How EU sanctions work: A new narrative’, Chaillot Papers No 129, European Union Institute for Security Studies, May 2013.

3: World Integrated Trade Solution, ‘China trade balance, exports and imports by country 2019’.

4: C News, ‘Krupneyshiy goszakazchik ‘Zheleza’ na ‘El’brusakh’ dumayet o vozvrashchenii na protsessory Intel’ (The largest state customer of hardware at Elbrus is thinking about returning to Intel processors), February 22nd 2022.

5: UK Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, ‘Russia’, July 21st 2020.

6: Andrei Yermakov, Irina Romashova and Natalia Dmitrieva, ‘Vliyaniye “Krymskykh” sanktsiy na ekonomiku Rossii i bor’ba za ikh otmyenu’ (The influence of the ‘Crimean’ sanctions on the economy of Russia and the struggle for their lifting), The State Counsellor, 2019.

7: Ian Bond, Christian Odendahl and Jennifer Rankin, ‘Frozen: The politics and economics of sanctions against Russia’, CER policy brief, March 16th 2015.

8: Frank Umbach, ‘What if Russia cuts off gas to Europe? Three scenarios’, gisreportsonline.com, February 14th 2022.

9: Ben McWilliams and others, ‘Preparing for the first winter without Russian gas’, Bruegel, February 28th 2022.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy and Zach Meyers is a senior research fellow at the CER

March 2022

View press release

Download full publication