Can European defence take off?

- Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 highlighted Europe’s lack of preparedness for conflict and pushed Europeans to increase defence spending. The EU’s role in defence has also deepened significantly. The Union is now involved in defence research, in fostering joint procurement and in financing the expansion of defence production.

- However, Europe’s ability to support Ukraine militarily remains constrained, while Russia’s production capacity is surging. Europeans need to redouble their efforts if they want to affect the outcome of the war. The EU’s policies in the defence industrial field will have a tangible impact on whether Europeans can increase their support to Ukraine and reinforce their own ability to deter aggression.

- This policy brief takes stock of the EU’s involvement in defence matters. While the EU has made substantial progress, its initiatives have a mixed record. Most EU defence instruments are small, and they are not very embedded in national defence planning. More broadly, the Union’s involvement in defence is primarily aimed at strengthening Europe’s defence industry over the long-term, rather than quickly reinforcing military capabilities.

- The EU needs to focus more attention and resources on short-term priorities, fostering more joint procurement of already existing equipment and helping expand production capacity of critical defence materiel such as ground-based air defence interceptors and long-range missiles. EU investments in research and development will not have a tangible impact on the war in Ukraine, but they can play an important role in the long-term.

- Finding more money for EU defence will be difficult. There is little spare capacity in the EU budget and many member-states remain sceptical of joint borrowing. Off-budget funding could be an option, and finding ways to make existing funds go further will be essential. Cohesion funds and money from the post-COVID Recovery and Resilience Facility could be used to help expand production capacity for military capabilities. Encouraging more lending to the defence sector should also be a priority for EU leaders.

- If Europeans fail to build up their defence capacity, their ability to continue to support Ukraine will be constrained. Russia could gradually gain the upper hand in the conflict, especially if US support diminishes over the coming year. An emboldened Russia may then be tempted to test NATO’s defences – particularly if Donald Trump is re-elected and casts doubt on America’s willingness to defend allies, or if the US has to divert military assets to deal with a conflict in Asia.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was a pivotal moment for European and global security. The invasion triggered strong Western sanctions on Russia. The West also provided Kyiv with extensive support in the form of military equipment, financial assistance and military training. Spurred by their own unpreparedness for large-scale conflict, Europeans have taken some steps to buttress their defences and many countries have announced large increases in defence spending. However, European countries have now used up much of their pre-existing stocks of weapons and ammunition, and they are struggling to produce enough to supply Ukraine with what it needs to defend itself. As Russia rapidly scales up its own military production, it may gain the upper hand, removing any incentives for Putin to negotiate. If Russia prevails, an emboldened Putin may be tempted to capitalise on Russia’s strengthened military to test NATO’s defences in the Baltics, potentially leading to a catastrophic conflict.

The EU’s policies in the defence industrial field will have a tangible impact on whether Europeans can help Ukraine and reinforce their own ability to deter aggression. Since 2017 the EU has made significant strides in the defence industrial field, developing a set of tools to encourage member-states to develop and procure military equipment jointly, and to foster more interoperability between European military forces. The EU’s involvement in defence procurement has deepened after Russia’s invasion, and the Union has also emerged as a significant actor in providing Ukraine with military assistance and training.

This policy brief assesses the prospects for increased EU involvement in defence industrial matters, and the obstacles in the way of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s ambition to establish a ‘European defence union’. Ultimately, the future of EU involvement in defence depends on whether member-states will put serious funding and political capital behind EU defence efforts, or whether they will prefer to maintain the status quo.

The current state of European national defences

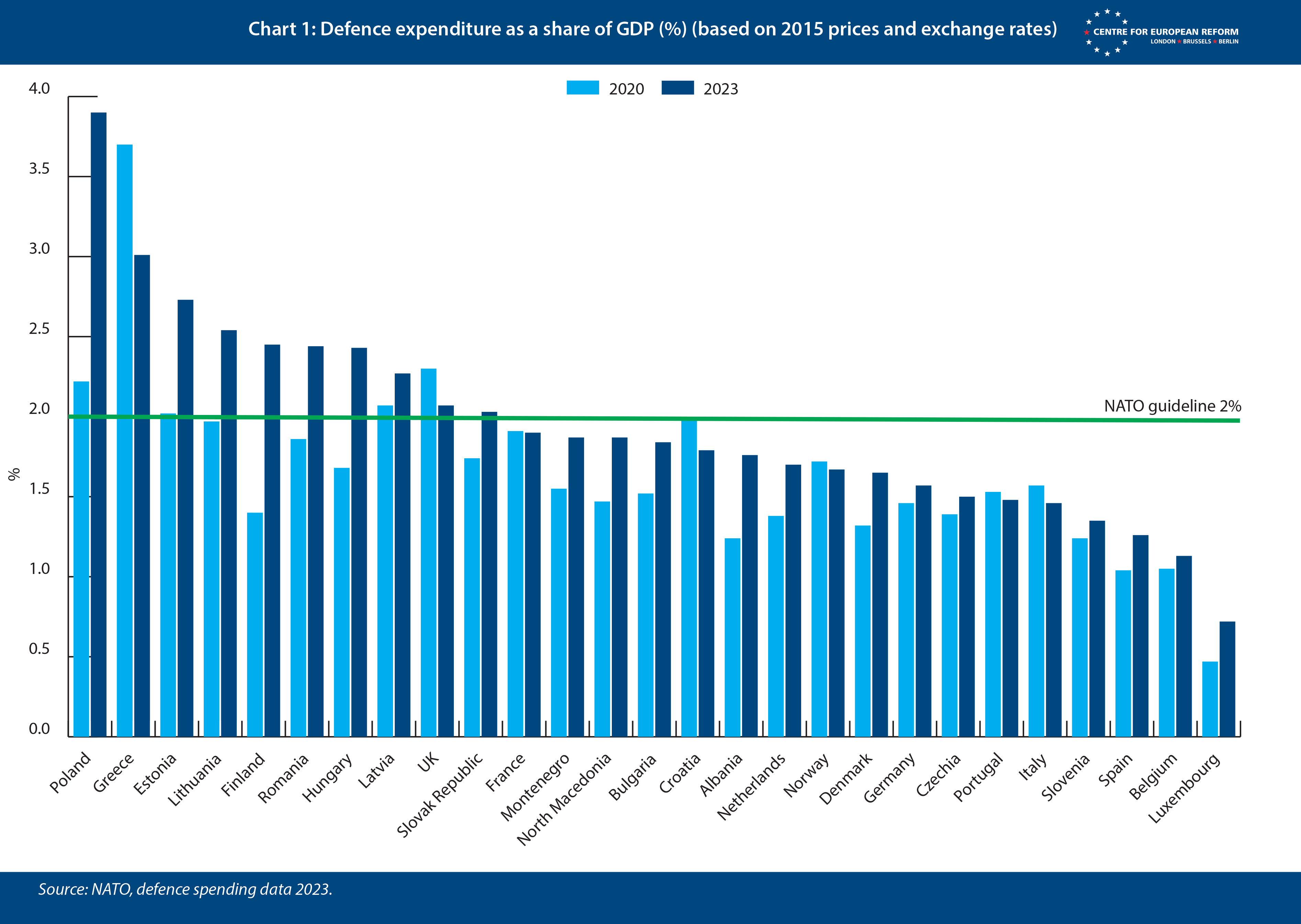

Most European countries neglected defence spending since reaping the ‘peace dividend’ at the end of the Cold War, with few meeting NATO’s target of spending 2 per of GDP on defence. For the past two decades, European countries’ attention largely focused on fighting non-state actors such as terrorists and insurgents, or weak states such as Libya. Budgets are now rising again after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to the latest annual report by the European Defence Agency (EDA), budgets rose by 6 per cent in 2022 and aggregate defence spending is now up by 40 per cent in real terms compared to 2014.1

Rising defence budgets have not yet translated into improved capabilities.

NATO figures show that the biggest increases were amongst countries closest to Ukraine such as Poland, which has increased its budget from 2.4 per cent of GDP in 2022 to almost 4 per cent in 2023.2 Western European countries’ budgets have also grown. Germany announced a large growth in defence spending, allocating an extra €100 billion through a special budget. France launched a large programme of defence investments, with its multi-year budget growing from €295 billion in 2019-2025 to €413 billion for 2024-2030. Meanwhile, according to the EDA, in 2022 Sweden increased its budget by 30 per cent year-on-year and Spain by 19 per cent.

However, rising budgets have not yet translated into improved capabilities. In some countries high inflation is reducing the value of nominal increases in defence spending – according to NATO figures, as a percentage of GDP Britain was expected to spend less on defence in 2023 than in 2014.3 Other countries have struggled to live up to their promises and face challenges in meeting their commitments: it is unclear how Germany will maintain its increased defence budget after the money from the €100 billion special fund runs out, and there are doubts over Poland’s ability to buy all the equipment that it wants to.4 Meanwhile, Italy, currently the third largest defence spender in the EU, has said it will not meet the 2 per cent target until the late 2020s.

There are also a range of practical obstacles that European countries face in increasing their defence production. Europe’s defence industrial base shrunk after the Cold War and is fragmented along national lines. It is structured to produce in relatively low volumes and has struggled to increase its output. Lack of certainty over the trajectory of defence budgets and future orders also makes many companies unwilling to make costly investments in expanding their production capacity. The continuing lack of co-ordination between member-states in investing their defence budgets is making it difficult to generate economies of scale and has given rise to competing orders.5 Finally, Europe’s reliance on imported critical raw materials is also leading to further delays.

These difficulties in increasing defence production mean that, almost two years into the war, Europe’s ability to support Ukraine militarily remains constrained. EU member-states will struggle to fulfil their promise to provide Ukraine with 1 million artillery shells by March this year: by December only around 300,000 had been delivered. The US, which faces political difficulties in continuing to support Ukraine due to the stance of some Republican Party representatives, will not be able to make up for the shortfall easily. According to one estimate Ukraine will need 2.4 million rounds of ammunition this year, but its partners may only be able to provide it with half as much.6 Similar challenges can be identified for air defence interceptors, drones and long-range missiles. In contrast, the Russian economy has gone onto a partial war footing. Its production of military kit, including ammunition, missiles and drones, is surging. For example, production of artillery ammunition tripled to 3.5 million shells in 2023 and will increase by a further million this year. Russian production of Iranian-designed Shahed drones is set to double, potentially allowing it to exhaust Ukraine’s air defences.7

The EU’s deepening role in defence before 2022

Aside from leading to significant increases in defence spending in Europe, Russia’s invasion has also led to a significant deepening of the EU’s own role in defence, as member-states have turned to the Union to try to increase their defence production. Before turning to the latest developments, however, it is worth recalling the context of the EU’s involvement in defence.

The EU’s tools are not the only means to foster more defence industrial co-operation in Europe. Many member-states co-operate bilaterally or in small groups. The Eurofighter/Typhoon aircraft stands out as the leading co-operative project, a joint endeavour between Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion, Germany and other European countries are banding together in the framework of the European Sky Shield initiative to acquire off-the-shelf air defence equipment and missiles. Some co-operation takes place through the Organisation for Joint Armament Co-operation (OCCAR), an intergovernmental organisation whose members are Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. OCCAR has been involved in the joint procurement of many complex projects such as the A400 military transport aircraft and the FREMM multi-purpose frigate. Meanwhile, NATO has a support and procurement agency (NSPA) that plays an important role. especially in logistics and maintenance. In recent years, OCCAR and the NSPA have worked together with the EDA to deliver an Airbus-made aerial refuelling and military transport aircraft.

There is limited European co-operation in defence procurement and linked fields.

The EU’s efforts in defence industrial policy have largely aimed to address the issue of fragmentation. Individual member-states carry out defence planning and acquisition separately and there is no effective process to co-ordinate these processes. Co-operation in defence procurement is very challenging. It is difficult for countries and firms that are trying to work together to agree on what each side sees as a fair division of the workshare. Each partner may insist on specific features, complicating a project and potentially resulting in multiple variants of what is theoretically the same piece of equipment. Costs can increase significantly – though domestic procurement is not immune from this problem either. Financing co-operative projects can be challenging, as a change of government in one partner can result in the withdrawal of funds. Navigating different countries’ export control regimes can also be an issue, if some partners fear that their counterparts will sell jointly developed equipment to countries that they do not want to do business with or, conversely, that partners will make export sales difficult by denying permission to sell.8

These difficulties mean that there is limited European co-operation in defence procurement and linked fields such as maintenance or logistics. According to the EDA, co-operative procurement stood at 18 per cent of all procurement in 2021 (the latest year for which figures are available). Meanwhile, collaborative defence research and technology stood at 7.2 per cent of all defence research and technology spending in 2022.9 Europe’s defence industry is also fragmented. Defence companies are primarily national, with a few exceptions such as Airbus and MBDA. National governments control demand and dictate who companies may sell to. Additionally, many member-states buy off-the-shelf equipment from non-European suppliers, especially the US. Limited co-operation makes it difficult to achieve sizeable economies of scale, and means that industries produce in relatively low numbers, and that production takes a long time. European militaries end up with a wide variety of non-standardised military equipment – a study by the Munich Security Conference found that in 2016 European armies had 178 types of major weapons systems, whereas the US had 30.10 This leads to additional maintenance and logistics costs and hinders interoperability. According to a 2019 European Parliament report, in financial terms lack of co-operation was costing at least €22 billion a year.11

Before 2016, the EU’s approach to fostering co-operation was based largely on regulatory sticks, trying to push member-states to be less protectionist. In 2009 the EU adopted two directives to that effect, one on trying to open national defence tenders to pan-European competition and one aimed at simplifying the rules on transferring defence products across EU borders. However, these met opposition from the member-states, concerned about potential job and revenue losses for their own defence industries, and unwilling to give up national controls over transfers of military equipment. Member-states have been able to avoid implementing EU defence directives by invoking the exemption based on essential national security interests contained in Article 346 of Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which states that an EU member “may take such measures as it considers necessary for the protection of the essential interests of its security which are connected with the production of or trade in arms, munitions and war material”.

In parallel, the Commission tried to pursue an incentive-based approach by promoting more joint defence research. The Commission has been involved in supporting research on security and dual-use technology through its research programmes since 2004.12 In the same year, impetus from both member-states and industry led to the creation of the EDA to focus on joint research, development and procurement. The EDA developed specific expertise in harmonising requirements and helping member-states develop co-operative projects. However, its resources were limited (largely due to the UK blocking the agency’s budget increases), and the agency was not taken particularly seriously by the member-states.13

The Commission has been supporting research on security and dual-use technology since 2004.

Following the UK’s decision to leave the EU in 2016, the idea of greater involvement by the EU in defence industrial matters gained ground, as London realised blocking EU initiatives of which it would not be part made little sense. In 2017, the EU launched a Preparatory Action on Defence Research, worth €90 million for two years. In 2019, this was followed by a European Defence Industrial Development Programme, a €500 million instrument to fund co-operative defence capability development. These two tools, managed by a new directorate-general for defence industry and space, were designed to show that EU involvement in defence had added value. They were direct precursors to the European Defence Fund (EDF), launched in 2021. Like its predecessors, the EDF aims to promote more joint R&D, in the hope that this will then lead to joint procurement. The EDF has a budget of €7.9 billion between 2021 and 2027 inclusive. To obtain financing from it, companies have to form multinational consortia, to incentivise cross-border co-operation. In the same year, the EDA launched a new planning tool, the Co-ordinated Annual Review on Defence, which is supposed to foster more co-operation by helping to systematically identify opportunities for defence collaboration between member-states.

At the same time as the Commission deepened its involvement in defence, in 2017 the member-states agreed to activate the treaty-based enhanced co-operation framework named Permanent Structured Co-operation (PESCO). PESCO, which now involves all member-states aside from Malta, is made up of two layers. The overarching layer involves all participating member-states, which sign up to a set of politically binding pledges, such as increasing their defence spending, and working together more closely on defence issues. Then there is a project layer, which currently involves 68 projects. Some projects aim to develop military capabilities, while others are designed to foster interoperability between military forces, for example through joint training. Perhaps the best-known example of the first sort is the programme to build a European drone, and of the second kind the military mobility project, which aims to facilitate the movement of troops and military kit across European countries.

Another very significant development prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the EU’s decision to establish a European Peace Facility (EPF) in 2021. The EPF is a financial instrument that sits outside the EU budget and is currently worth €12 billion between 2021 and 2027. It is designed to finance EU actions to assist partners, including by providing lethal assistance.

The impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on EU defence

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 sparked a further deepening of EU involvement in defence. The EU has provided Ukraine with €5.6 billion in military assistance through the EPF, by reimbursing member-states for some of the cost of the material they have donated to Kyiv. This marked the first time that the EU has provided military help to a country at war. There are discussions about setting up a separate funding line dedicated solely to Ukraine, worth up to €20 billion over four years. The EU’s involvement in defence production has also increased. With their March 2022 Versailles declaration, steered by French President Emmanuel Macron, EU leaders agreed they would invest “more and better in defence capabilities” and tasked the Commission to analyse the key challenges in defence investment and propose steps to strengthen it. In May 2022 the Commission produced its analysis, setting out the key challenges facing European defence industrial production.14

In the months that followed, the EU launched several new initiatives. A Defence Joint Procurement Task Force mapped production capacity for specific types of equipment across Europe, identifying bottlenecks in supply chains. In July 2023 the EU finalised the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP), a tool through which EU funding is used to support efforts by defence firms to increase ammunition production. ASAP has a budget of €500 million over two years. In October 2023, the EU launched the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through common Procurement Act (EDIRPA). Worth €300 million over two years, EDIRPA targets the demand side of the equation. It is meant to encourage member-states to procure defence equipment jointly by offering EU funding to subsidise the cost of co-operation, particularly the administrative costs of jointly procured products. EDIRPA is also meant to provide a structured framework in which to co-operate. While both ASAP and EDIRPA are small, they mark the EU becoming much more closely involved in defence. Because the EU treaties prevent the EU budget from being used for military expenditure, the EU’s defence instruments have their legal basis in industrial policy, and are in principle aimed at fostering competitiveness and cohesion.

In addition to encouraging the Commission to develop new defence industrial tools of its own, Russia’s war on Ukraine has prompted member-states to turn to the EPF to finance joint procurement (which was not the fund’s original intended purpose). In May 2023, EU leaders agreed to use €1 billion from the EPF to jointly acquire 1 million pieces of 155mm artillery ammunition and potentially also missiles for Ukraine, sourced from the European defence industry. It was much easier for the EU to agree on joint procurement via the EPF than EDIRPA or ASAP, as the EPF is not formally part of the EU budget and only requires agreement between the member-states rather than lengthy inter-institutional negotiations.

The Commission wants to follow-up EDIRPA and ASAP with a larger programme, the European Defence Investment Programme. This should contain new incentives to further encourage member-states to procure equipment jointly. The investment programme will form part of a broader European Defence Industrial Strategy, which is supposed to give a greater sense of purpose and direction to EU efforts in defence. The release of the two documents has been delayed, but they are currently set to be published in the first quarter of 2024.

The challenges of EU defence initiatives

The EU’s role in defence has changed significantly since 2016, particularly since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Union has, or is developing, a range of tools to strengthen European military capabilities, especially by fostering more joint research and development, procurement and interoperability. But these efforts have had a mixed record and often remain of a limited financial scale.

The EU’s defence efforts have a mixed record and often remain of a limited financial scale.

PESCO has in many ways been a disappointment. Its premise was to bring about a gear-shift in EU defence co-operation. In reality, the ‘binding commitments’ that member-states signed up did not have a meaningful impact – the sizeable uptick in European defence spending came after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Some of the 68 existing PESCO projects, such as military mobility or the Eurodrone, are valuable. But analysts rightly note “the continued tendency of member-states to launch low-level and low-impact projects”.15 Additionally, many projects are not progressing and there is little that ties them together into a coherent whole.

It is too early to judge the EDF: because it finances R&D, it will take many years for its impact on procurement and capabilities to make itself felt. Nevertheless, its prospects seem positive. The money on offer is a powerful inducement for defence firms to work together, and EDF calls for projects are attracting significant interest from would-be participants. At €7.9 billion over seven years, the EDF is also a sizeable tool. For comparison, in 2022 the R&D spending of the 26 EU members that are EDA members amounted to €9.5 billion, meaning that the EDF added almost 12 per cent to EU yearly defence R&D spending.16 Nevertheless, the EDF’s effectiveness will ultimately depend on whether the projects that it funds end up being used in capabilities that the member-states procure. One potential issue is that EDF funding is split between a relatively large number of projects, each made up of many entities from several member-states. Historically, large co-operative projects have been unwieldy, and EU funds would have a higher impact if they focused on a few high-impact projects with fewer participants. But that would almost certainly mean that most funds would go to large defence contractors in the big member-states, annoying other member-states.

The instruments launched since Russia’s invasion, ASAP and EDIRPA, are too small to have a significant impact. Additionally, there were long delays in adopting EDIRPA and arguments between member-states over the degree to which it would allow the purchase of equipment containing components of non-EU origin. That meant that EDIRPA functioned more as a test case for EU involvement in supporting joint procurement,rather than serving its stated purpose of helping member-states quickly fill urgent capability gaps.

The EPF has been successful in Europeanising support for Ukraine, providing domestic political cover for governments that were less keen on donating military equipment to Ukraine to do so.17 The EPF also allowed for some European solidarity, with richer member-states subsidising donations of smaller countries. However, the joint procurement of ammunition for Ukraine through the EPF is encountering delays, and the EU will struggle to meet its target of sending one million rounds to Ukraine by March 2024. EU High Representative for foreign policy Josep Borrell argued that delays are due to European suppliers prioritising orders from their existing customers over Kyiv’s needs.18 Others, like internal market Commissioner Thierry Breton have blamed member-states for being slow in placing orders.

There have been disagreements over the EPF’s functioning, with some countries criticising Estonia for how it used the fund to claim reimbursement for new kit to replace older equipment donated to Ukraine. France thinks that the EPF funds should be restricted to financing European-made equipment only, and Germany has grown very sceptical of the EPF, saying it wants to detract its own bilateral assistance to Ukraine from its contributions to the EPF. The biggest problem with the EPF, however, is the need for consensus. That is a serious drawback, as demonstrated by how Hungary has been vetoing additional disbursements since last spring.

Lack of co-ordination in planning and spending budgets means that opportunities for co-operation are regularly missed.

Looking beyond the individual tools, one of the main challenges for EU defence is that its planning tools are not binding and not sufficiently embedded in national defence planning. EU tools are still relatively new, and member-states take them less seriously than NATO’s long-standing defence planning process. The EU’s planning also lacks focus. The 2023 iteration of the overarching Capability Development Plan contains 22 priorities, making it difficult to identify real priorities. Additionally, the degree of coherence of EU defence planning tools needs improvement: the capability prioritisation processes in PESCO and EDF are not fully aligned with the guidance of the overarching Capability Development Plan. As a result, member-states carry out defence planning in an unsynchronised fashion, and lack of co-ordination in the planning and spending of budgets means that opportunities for co-operation are regularly missed.19 The rush to refill stocks since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is emblematic of the lack of co-ordination, with countries largely going their own way, exacerbating fragmentation.

Another challenge relates to the EU’s chosen strategy. The Union has focused on promoting the development of new homegrown capabilities through the EDF, potentially a decades-long effort, rather than prioritising shorter-term military needs, for example by expanding production of existing capabilities. The EU has also chosen to make its defence initiatives fairly closed to non-EU countries (except for Norway as a member of the European Economic Area). Restrictions on third country participation are not overt but stem from the EU’s stipulation that the products of its programmes should not be subject to third-country restrictions. That makes third countries worry about their ability to freely use, export and innovate on products developed within EU tools. The EU stresses that its conditions for third country access are based on reciprocity, with the US also imposing restrictions on the ability of third-country firms to operate on its territory or to re-export equipment containing American-made components. The EU’s decision to restrict third-country participation will probably benefit its defence industry; but its advantages when it comes to developing capabilities quickly and efficiently are less clear.

EU defence initiatives have also been hindered by the fact that many member-states worry about Commission overreach. This was visible during the negotiations over ASAP. The Commission had proposed that it should have the power to push member-states to prioritise some orders over others, a measure that was stripped out of the final version of ASAP. The Commission had also wanted to be able to push member-states to share information about their defence production capabilities and supply chains, and to include measures to facilitate transfers of defence equipment between countries. However, many member-states did not like these proposals, and they were removed from ASAP during negotiations. More broadly, many member-states are wary of sharing information about their defence production capacity or supply chains with the Commission and are very sceptical of a more binding defence planning process that could result in it dictating their procurement decisions.20

Finally, lack of trust between member-states holds back EU defence efforts. The war in Ukraine has revealed deep levels of mistrust between many countries. In particular, the Baltic states and Poland continue to view France and Germany as laggards in providing military support to Ukraine, and as too concerned about escalation. Therefore, EU members along NATO’s eastern flank prefer to buy ready-made equipment from the US or other suppliers like South Korea. Interest in PESCO and EDF projects mainly comes from firms and countries in Western and southern Europe, in particular France, Germany, Spain, Italy and Greece.21

However, defence relations within Western Europe are also not smooth: France and Germany are jointly developing a next generation main battle tank and fighter jet, but both projects are in trouble. There are differences over their timeframes, specifications, the division of labour, and the approach to arms exports. Defence relations between France and Italy are also complicated. Recent years have seen Paris and Rome veto reciprocal acquisitions in the defence sector, most recently in November 2023 when Italy prevented France’s Safran from taking over an Italian company involved in the manufacture of the Eurofighter, arguing that production could not be guaranteed if the transaction went ahead.

What next for EU defence?

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said she wants the EU to move towards a so-called defence union. The Commission is set to announce more details about what this will entail in the first few months of 2024, but the idea is to make defence planning more co-ordinated, and to provide more financial incentives for EU countries to procure equipment together. The Commission is concerned that the impact of greater defence investments since Russia’s invasion is being blunted by lack of co-ordination and worries that member-states’ purchases of non-EU kit are exacerbating fragmentation.

The EU needs to focus more attention and resources on short-term priorities.

The Commission has mooted several ideas. Von der Leyen has talked of a “strategic planning function that ties together national and EU-level planning” to “reduce fragmentation on the demand and supply sides.” She has also mentioned a new regulatory framework to provide more predictability and coherence in defence planning. Von der Leyen has also spoken of potentially identifying so-called ‘flagship capabilities’ to focus on, mentioning cyber, satellites, strategic transportation and air defence.22 The Commission has highlighted the need for EU initiatives to be well-funded, and has put forward ideas such as reducing VAT on co-operative projects, and encouraging more lending to the defence sector. The European Investment Bank (EIB) cannot finance ammunition or weapons, but only dual use equipment. Meanwhile the rise of ESG reporting and investing is discouraging private investment in defence. Defence is not classified as environmentally sustainable by the EU Taxonomy framework to identify sustainable activities, but defence is not seen as incompatible with social sustainability. Nevertheless, many financial operators are excluding defence companies from sustainable investment funds and at times mainstream funds as well.

Despite the Commission’s ambitions, joint EU defence planning and large-scale procurement are likely to remain unacceptable to most member-states for the foreseeable future. That means that the EU’s role is likely to be limited to facilitating co-operation through recommendations and incentives rather than being able to push the member-states to work together. That makes it imperative for the EU to have an effective strategy and for the incentives it provides to be as attractive as possible.

The EU needs to focus more attention and resources on short-term priorities. The EU should focus on fostering more joint procurement of existing equipment and on expanding production capacity for it. For example, Ukraine needs large numbers of ground-based air interceptors, missiles and spare parts such as replacement artillery barrels. The EU could foster production in three different ways. First, it could expand the EDIRPA approach, offering substantial incentives to foster joint procurement of such equipment. Second, the EU could copy the model of the joint ammunition order through the EPF for other types of kit. Third, the EU could replicate ASAP’s approach of directly funding ammunition production capacity for other types of materiel. These approaches are not mutually exclusive. The EU could fund the expansion of production for a certain piece of equipment – say ground-based interceptors – while also pooling orders through a common fund.

In the medium term, much depends on whether the EU can succeed in identifying a handful of priorities for capability development through the EDF. If there are too many, defence initiatives will lack focus and EU funding will be dispersed. Concentrating EDF funding on a smaller set of capabilities would signal a strong EU commitment for their development and make the most of limited resources. New capabilities that most member-states have not yet devoted great attention to, such as those relating to low-cost mass-produced drones and cyberwarfare, may be particularly promising. There is also a strong case for the EU to restrict the number of EDF grant beneficiaries. The greater the number of participants in a project, the more unwieldy and the less likely to generate capabilities it will be. Doing so would maximise the chances that any capabilities developed within the EDF will be taken up by member-states for joint procurement.

Funding EU defence will be challenging. Negotiations over the ‘mid-term review’ of the current seven-year EU budget cycle will probably lead to an extra €1.5 billion for the EDF.23 That would create space to refinance ASAP and EDIRPA beyond their expiry in 2025 but leave very little for anything more ambitious. The EU budget is stretched and subject to strict spending ceilings, and member-states seem unwilling to come up with more money for defence, given the huge range of competing priorities. Using the EPF seems problematic as it requires all member-states to agree. Setting up another off-budget instrument from a coalition of the willing could be useful in overcoming vetoes, and such a fund could also be open to participation by non-EU partners. Another idea would be directing more resources to defence through further joint EU-level borrowing on the model of the Next Generation EU recovery fund, or through the ‘defence bonds’ recently mooted by European Council President Charles Michel. But such a scheme would require unanimity and the more ‘frugal’ member-states insist that the recovery fund was a one-off.

Finding new funds requires member-states to realise that their own security is at stake.

Finding new funds requires member-states to realise that their own security is at stake, and to persuade their own citizens of that. But there are ways of making existing sources of funding stretch further. The Commission argues that there are no legal impediments to member-states using EU cohesion funds to finance measures that help the defence industry, meaning there is potentially a large source of funding for initiatives designed to expand defence production capacity on the model of ASAP.24 There may also be scope to redirect some funds from the Recovery Fund for the same purpose. Conversely, relaxing the EU’s fiscal rules to fully exclude defence spending from counting towards budget deficits is not politically feasible, though there may be some leeway to view spending on co-operative defence projects favourably. The Commission should push on with its idea of exempting co-operative procurement projects from paying value added tax (VAT), to make them more appealing. Finally, EU leaders need to clarify that they see defence as a common good, and that public and private financial institutions should be willing to lend to it. While there may be no consensus between member-states to loosen the EIB’s lending policy beyond its current limit to dual-use goods, EU leaders should clarify that they see defence as essential and fully compatible with ESG goals.

Finally, the EU should revisit the question of how open its defence initiatives are to non-EU partners. In the long-term, it makes sense for EU initiatives to encourage the strengthening of Europe’s defence industrial base. If European countries stop innovating and developing their own defence equipment, Europe’s defence base will atrophy and Europeans will completely depend on external suppliers. It is not difficult to imagine a Trump-like US President taking advantage of Europe’s dependency. Still, when it comes to the short term, an emphasis on made in Europe comes at the expense of effectiveness, because equipment that depends on foreign components may be the best available option. In general, rather than taking a blanket approach to third country involvement, the EU would be better served by a more flexible stance based on a case-by-case assessment of risks and benefits. There is a particularly strong argument for more closely involving the UK, give its deep pre-existing defence partnerships with many EU countries.25

Conclusion

The future of European security will depend in large part on whether Europe is able to expand its capacity to support Ukraine over the coming years. Much hinges on whether planned defence spending increases go ahead, and on whether Europeans can deepen co-operation to maximise the efficiency of their spending. The EU can play a constructive role in that effort, helping improve capabilities and fostering more defence co-operation.

The Union’s involvement in defence industrial matters has deepened since 2016, but its initiatives need to be expanded further to have a real impact. The EU also needs to focus more attention on short-term military needs that will assist Ukraine. Because member-states are unlikely to be receptive to approaches that limit their room of manoeuvre through regulation, the Union should focus on doing what it can to fund the expansion of defence production, and to provide appealing incentives for countries to co-operate. However, this will only work if more money can be found.

If Europeans succeed, they can make a decisive contribution to Ukraine’s continued war efforts, helping to persuade Russia that its war is unwinnable. Europe would also be in a stronger position to weather the storm of a possible second Trump presidency, and to look after its own security as the US devotes more resources and attention to countering China’s assertiveness in Asia. Conversely, if Europeans fail, the risk of Moscow gaining the upper hand in the conflict will grow, potentially paving the way for an emboldened Russia to prod NATO’s defences.

2: NATO, ‘Defence Expenditures of NATO Countries (2014-2023)’, July 7th 2023.

3: NATO, ‘Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2023): Defence expenditure as a share of GDP. Based on 2015 prices’, July 7th 2023.

4: Raphael Minder, ‘‘Who will pay the bill?’: Poland’s defence spending spree raises questions over funding’, Financial Times, April 23rd 2023.

5: European Commission, ‘Joint communication: Defence investment gaps analysis and way forward’, May 23rd 2022; European Commission, Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space, ‘Issue paper 2: Towards a European Defence Industrial Strategy: Investing better and together in defence capabilities and innovative technologies’, December 7th 2023.

6: Jack Watling, ‘The War in Ukraine Is Not a Stalemate’, Foreign Affairs, January 3rd 2024 ; Estonian Ministry of Defence, Discussion paper: ‘Setting Transatlantic Defence up for Success: A Military Strategy for Ukraine’s Victory and Russia’s Defeat’, December 17th 2023.

7: Estonian Ministry of Defence Discussion paper: ‘Setting Transatlantic Defence up for Success: A Military Strategy for Ukraine’s Victory and Russia’s Defeat’, December 17th 2023.

8: Sophia Besch and Beth Oppenheim, ‘Up in arms: Warring over Europe’s arms export regime’, CER policy brief, September 10th 2019.

9: The EDA caveats this figure saying it is based on limited data, so in reality co-operation may be higher.

10: David Bachmann et al., ‘More European, More Connected and More Capable: Building the European Armed Forces of the Future,’ Munich Security Conference, McKinsey, and Hertie School of Governance, November 30th 2017.

11: European Parliamentary Research Service, ‘Europe’s two trillion euro dividend: Mapping the Cost of Non Europe, 2019-24’, April 2019.

12: Raluca Csernatoni, ‘The EU’s Defense Ambitions: Understanding the Emergence of a European Defense Technological and Industrial Complex’, Carnegie Europe, December 6th 2021.

13: Frédéric Mauro, Klaus Thoma, ‘The future of EU defence research’, European Parliament Directorate General for External Policies, March 30th 2016.

14: European Commission, ‘Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Commitee of the Regions on the Defence Investment Gaps Analysis and Way forward’, May 18th 2022.

15: Daniel Fiott and Luis Simon, ’EU defence after Versailles: An agenda for the future’, Analysis Requested by the SEDE subcommittee of the European Parliament, October 3rd 2023.

16: Calculation based on the EDA’s 2022 data. EDA, ‘Defence data 2022: Key findings and analysis’, November 29th 2023.

17: Tyyne Karjalainen and Katariina Mustasilta, ‘European Peace Facility: From a conflict prevention tool to a defender of security and geopolitical interests’, Trans European Policy Association Policy Brief, May 30th 2023.

18: Tom Kington, ‘Euro leaders blame industry for failure to meet Ukraine ammo promise’, DefenseNews November 15th 2023.

19: European Commission, Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space, ’Issue paper 2: Towards a European Defence Industrial Strategy: Investing better and together in defence capabilities and innovative technologies’, December 7th 2023.

20: Jacopo Barigazzi and Laura Kayalieu, ‘Heavyweights warn against Commission defense power grab’, Politico EU, November 28th 2023.

21: Spyros Blavoukos, Panos Politis, Thanos Dellatolas, ‘Mapping EU Defence Collaboration one year on from the Versailles Declaration’, ELIAMEP, April 2023.

22: Ursula von der Leyen, ‘Keynote speech at the EDA Annual Conference 2023: Powering up European Defence’, November 30th 2023.

23: President of the European Council, ’Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027 Negotiating Box‘, December 15th 2023.

24: EU Directorate-General Defence Industry and Space, ’Issue paper 5: Mainstreaming defence industrial readiness culture throughout all policy areas at EU and national levels’, December 7th 2023.

25: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘EU-UK co-operation in defence capabilities after the war in Ukraine’, CER/KAS policy brief, June 9th 2023.

Luigi Scazzieri is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

January 2024

View press release

Download full publication