Ukraine fatigue: Bad for Kyiv, bad for the West

- It is increasingly clear that Ukraine cannot achieve a quick victory. But is it at risk of a quick defeat? The conflict in the Middle East is displacing Ukraine as the number one pre-occupation for Western leaders, and there is a risk that Ukraine will be pushed into a disadvantageous ceasefire with Russia, or left to fight on without enough Western aid to win.

- After Ukraine’s success in stopping Russia’s initial thrusts and then recapturing territory in 2022, there was optimism that it would be able to continue its rapid advances in 2023. But it has made very little progress against entrenched Russian forces. Ukraine relies heavily on Western military help, which continues to come too slowly and in too small quantities. Meanwhile, Russia has announced a 70 per cent increase in its defence budget for 2024, and is getting ammunition and missiles from North Korea and Iran. But it may be hard for Russia to sustain its current level of defence spending over the long term.

- The Ukrainian economy shrank by almost 30 per cent in 2022, but has made a small recovery this year. It is less than a tenth the size of the Russian economy, however. Given the damage to key sectors of the economy, and the cost of the war and of post-war reconstruction, Ukraine will remain dependent on external financing for the foreseeable future. Sanctions against Russia have had some impact on specific sectors, but they have not been as effective as Western policy-makers and analysts hoped.

- Some Western leaders are showing signs of ‘Ukraine fatigue’; others were never enthusiastic supporters of Kyiv. On both sides of the Atlantic the prospects for additional aid for Ukraine are worsening. The conflict in the Middle East is distracting attention from Ukraine. Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, is the main beneficiary of this shift of focus.

- The EU must take a strategic approach to Ukraine, starting with a clear definition of its goal – Ukraine’s recovery of all its territory and its integration into the EU. Putin must not be allowed to hope that if he keeps fighting long enough the West will lose interest in Ukraine.

- The opening of EU accession negotiations in 2024 would be an important signal of lasting commitment to Ukraine, but is only the start of a long road to membership.

- The West needs to give Ukraine both short- and long-term military support, and Europe needs to increase defence budgets and rationalise how they are spent. EU fiscal rules risk getting in the way, however.

- The EU needs to plan for Ukraine’s (enormous) recovery needs. The EU should not be so squeamish about confiscating frozen Russian assets and using them to repair the damage Russia has done.

- Last year, the EU and NATO indicated that Ukraine should eventually be a member of both organisations. This year some leaders seem to want to forget what they said in 2022. But they should not deceive themselves into thinking that Putin is looking for a compromise solution: he still believes he can win. If Ukraine does not prevail, the consequences for European security will be serious. The cost of helping Ukraine is high; the cost of not helping it will be higher.

The European Union’s High Representative for foreign affairs and security policy (HRVP) Josep Borrell spoke at the CER’s conference on ‘Europe and the World’ on October 24th 2023. His comments on Ukraine were particularly striking: “I know a way to finish the war quickly… I stop supporting Ukraine and the war will finish, by surrender of the Ukrainians.… [But] If Putin wins this time, who is next?”. It has become increasingly clear that there will be no quick victory for Ukraine, certainly not this year. The West, and above all European leaders, must decide whether to keep helping Ukraine, however long it takes to defeat Russia, or to look for some other outcome.

Ukraine’s efforts to recover control of its territory from Russia are reaching a critical moment. While Ukraine’s ground offensive is more or less stalled, the war between Israel and Hamas has knocked Ukraine off the front pages. Though European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen paid her sixth visit to Kyiv on November 4th, and the Commission recommended on November 8th that the EU should open accession negotiations with Ukraine, it is no longer the top issue at every European Council meeting, as it has been since Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. These are dangerous times for Ukraine, politically and militarily.

Ukraine’s supporters in Europe cannot afford to be distracted by events in the Middle East, serious though those are. There is a growing risk that the West will either push Ukraine into a disadvantageous ceasefire, leaving Russia in control of almost a fifth of Ukrainian territory, or leave Ukraine to fight on, but with much more limited military and financial assistance, enabling Russia to advance even further. Either outcome would be disastrous, not only for Ukraine, but for European security.

This policy brief looks at the military situation and the economic challenges facing Ukraine, and the political trends in the West, including the influence of the conflict in the Middle East on attitudes to support for Ukraine. It argues that the West, and in particular Europe, needs to look at the conflict in Ukraine strategically. Its initial aim should be to ensure that Ukraine can inflict a decisive defeat on Russia; its ultimate objective should be to integrate a secure, stable, democratic and prosperous Ukraine into Western institutions. The brief argues that the effort to achieve these objectives should be properly resourced, despite the high cost, recognising that the cost of dealing with the consequences of Russian success in Ukraine would be even greater.

The military situation

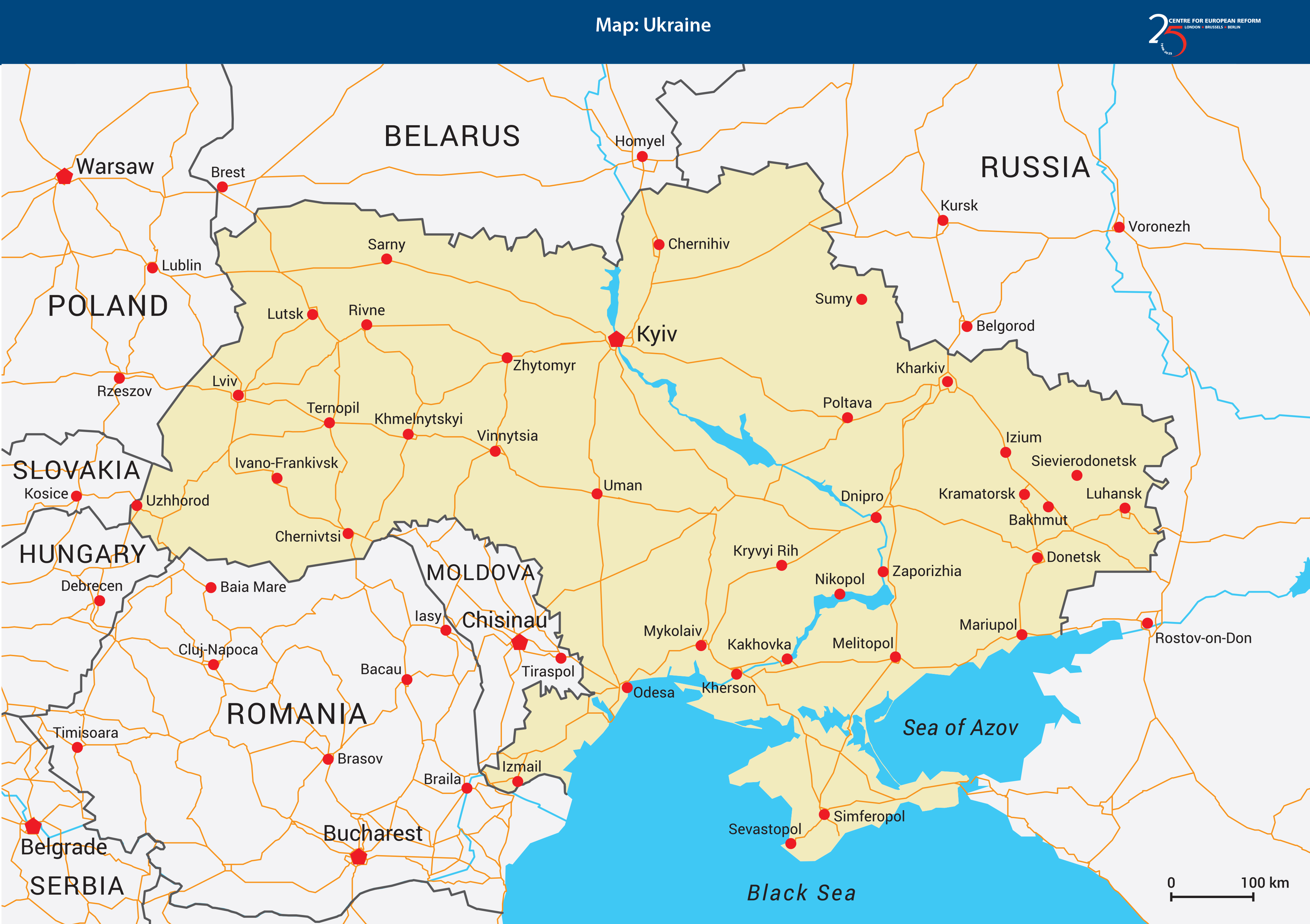

Putin began the land war on February 24th 2022 with multiple thrusts into Ukraine – initially making considerable gains in the north (where Russia’s offensive eventually stalled about 20 kilometres from Kyiv), north-east and south. Though Russia continued to expand its control of territory in the south and east, capturing the city of Mariupol on the Sea of Azov in May, by early April Ukrainian forces had driven Russian forces away from Kyiv. In the autumn Ukraine also liberated large areas to the east of Kharkiv, as well as the city of Kherson, on the west bank of the Dnipro river.

This led to a sense of optimism about the likelihood of further significant progress in 2023, even among Western military experts.1 But Russia has done better than expected so far in 2023 – even if the cost in casualties has been enormous. Largely by throwing human waves of untrained infantry recruited from Russian prisons at Ukrainian lines, the Wagner private military company was able to take the eastern city of Bakhmut in May. When the head of Wagner, Yevgeniy Prigozhin, led a mutiny the following month, many commentators, including me, thought that it was a sign of collapsing morale, and might be followed by more battlefield successes for Ukraine. Ukraine’s offensive, enabled by Western supplies of tanks, armoured vehicles and mine-clearing equipment, made some progress in the summer. But – thanks in part to well-designed lines of fortifications with minefields 15-20 kilometres deep in front of them – the Russians have yielded little ground. Ukraine had hoped to cut Russia’s ‘land bridge’ from Donetsk to Crimea, if not by reaching the sea then at least by keeping all of Russia’s transport routes at risk of artillery or missile strikes, but so far it has not been able to do so.

Russia has done better than expected in 2023 – even if the cost in casualties has been enormous.

Even the commander-in-chief of Ukraine’s armed forces, General Valeriy Zaluzhnyy, has said that the war “is gradually moving to a positional form”, in other words, that neither side is capable of taking much territory at present. He has warned that this will help Russia, which will have “the opportunity to reconstitute and build up its military power”.2

According to Zaluzhnyy, Ukraine has five main problems. One is lack of air assets. Even though the Russian airforce has been relatively ineffective throughout the conflict, it remains potent enough to prevent Ukrainian forces fighting as NATO forces would. If Ukraine had air superiority, its forces would face much less of a threat from drones, fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters. Another is a lack of mine-clearing equipment – compounded by Ukraine’s inability to protect what it has against being spotted from the air and targeted. A third is inadequate counter-battery capability – the ability to locate and strike back at Russian artillery quickly whenever it fires on Ukrainian positions. A fourth is a lack of electronic warfare capability – both defensive, to protect Ukrainian communications and navigation systems from Russian disruption, and offensive, to disrupt Russia’s systems. And finally, there is a lack of reserves. Ukraine’s pre-war population was about 43 million, but with about 8 million refugees (including almost three million relocated, voluntarily or otherwise, in Russia) and several million people living in areas under Russian occupation (and subject to Russian conscription), its current population has been estimated at 28-34 million.3 Russia’s population in 2023, according to UN estimates, is about 144 million. Even though Putin has so far refrained from ordering a general mobilisation – perhaps with the risk of popular discontent ahead of Russia’s March 2024 presidential election in mind – Russia has been able to recruit from a much larger manpower pool than Ukraine. There are also worrying signs that Ukraine is struggling to mobilise more troops: their average age has risen from around 35 at the start of the war to 43.4 Neither Russia nor Ukraine provide any official figures on casualties, but US estimates in July 2023 were that Russia had lost around 120,000 dead and around 180,000 wounded, while for Ukraine the figures were 70,000 and 100,000-120,000 respectively.5 Given the disparity in populations, those figures are bad news for Ukraine.

Paradoxically, Ukraine has done better at sea than on land, despite not having a navy. In September 2023 Ukrainian missiles struck and seriously damaged a Russian ship and submarine in dry dock in Sevastopol, the Black Sea Fleet’s main base, and the Black Sea Fleet headquarters in the town. Ukraine has subsequently been able to damage a Russian warship and the dockyard in the port of Kerch, on the eastern side of Crimea, and two Russian landing ships, at least one loaded with military equipment, on the western side of the peninsula. By early October, Russia had withdrawn most ships from Sevastopol and moved them to other ports out of range of Ukrainian missiles and maritime drones. By driving most of the Russian navy out of the western Black Sea, Ukraine was able to open a shipping corridor from Odesa through its territorial waters to the border with Romania and thence through Romanian and Bulgarian waters to the Bosporus. This enabled it to resume the export of grain (though Russia continues to attempt to disrupt this).

Ukraine could not have done as well as it has, at sea or on land, without the extensive support it has received from its Western partners. The Ukraine Defence Contact Group (or ‘Ramstein Group’, after the US airbase in Germany where its first meeting was held) brings together more than 50 countries, including all NATO members, to co-ordinate military aid to Ukraine. As of the end of July 2023, military aid worth almost €95 billion had been pledged or delivered.6

Ukraine’s partners have presented it with something of a logistic nightmare, however, because of the many different types of equipment they have supplied it with, requiring different spare parts and often different ammunition. The 875 main battle tanks pledged or delivered, for example, consist of a mixture of Soviet models or versions of them built in other Warsaw Pact countries before the end of the Cold War, plus at least six different types of Western tanks. Some of these (such as the German-built Leopard 2 and the US Abrams M1A1) use the same ammunition but others (notably the UK’s Challenger 2) require their own unique ammunition. NATO and other countries have supplied almost 20 types of towed and self-propelled artillery using four different calibres of ammunition – though Ukraine is increasingly using NATO-standard 155mm howitzers.

Western military supplies have from the start of the conflict been supplied too slowly and in inadequate quantities.

Moreover, Western military supplies have from the start of the conflict been delivered too slowly and in inadequate quantities. Even now, weapons systems that could potentially tilt the battlefield in Ukraine’s favour, such as the American ATACMS missile, with a longer range than other weapons available to Ukraine, have been supplied in numbers far too small to be decisive (the US seems to have sent Ukraine fewer than 12 ATACMS missiles, at least initially).7 Even if Ukraine gets more American help, it will now have to compete with Israel for access to dwindling US stocks of air defence missiles and ammunition (Israel is reportedly already getting some of the US 155mm shells, stored in Israel, that had previously been earmarked for Ukraine).8

Current Western ammunition production would be inadequate to meet Ukraine’s needs even if every shell produced went straight to the front line. The defence analyst Francis Tusa estimated in March 2023 that European production was around 500,000-600,000 155mm shells per year, and that Ukraine was using between 1.8 and 2.9 million shells a year (5,000-8,000 per day).9 The EU agreed in March 2023 to supply Ukraine with one million rounds of 155mm ammunition from stockpiles, and to replenish arsenals by increasing production, allocating €500 million under the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) to this end. But this sum is far short of what is needed to enable Ukraine to match Russia shell for shell, or even to ensure that it reaches the one million-round target. US production is predicted to reach 57,000 per month by spring 2024, and to rise to 100,000 per month in 2025.10 Even at that pace, US and European production would barely match Ukraine’s minimum rate of consumption, let alone be able to refill NATO stocks that (as is now clear) are far below levels needed to fight a conventional war in Europe. The West is still supplying Ukraine with enough weapons and munitions not to lose, but not enough to win.

On the other side, Russia has also received foreign help: according to reports from South Korea, North Korea has supplied more than a million artillery shells to Russia since early August. Russia has also bought Iranian kamikaze drones, and the technology to make them, and is reportedly looking at buying ballistic missiles from Tehran to supplement its own shrinking stocks (though it is not clear whether Iran will sell them, in case it needs them for itself in the conflict in the Middle East).

Moscow has announced a 70 per cent increase in Russian defence spending for 2024, to around €107 billion, or 6 per cent of its GDP.11 Russia’s increased defence budget will still only be a fraction of what NATO spends – the US defence budget for 2023 was $860 billion, with European allies and Canada contributing another $404 billion. But the US has to be mindful of other calls on its military resources (in the Middle East and beyond). European allies, procuring much of their equipment in small quantities and on a national basis, cannot match Russia’s lower production costs and economies of scale. The EU’s efforts to encourage more efficient procurement and discourage a proliferation of different national programmes are so far too small to make a decisive difference, as Luigi Scazzieri wrote in January 2023.12 In the long term, it may be impossible for Russia’s economy to sustain the current level of defence spending and commitment of resources to the defence industrial sector. But in the short to medium term, the West needs to step up its own effort considerably.

French President Emmanuel Macron said in June 2022 that France had “entered into a war economy”.13 France’s defence budget for 2024-2030, at €413 billion, is a 40 per cent increase on the current seven-year budget. But the reality is that no European country has moved to a war economy; no leader is redirecting industry to focus on war production. Meanwhile, Putin is mobilising the remnants of the Soviet Union’s military industrial complex to modernise old equipment and produce weapons systems that may be less sophisticated than their Western counterparts, but can be delivered more quickly and in larger numbers. He can also put mothballed Soviet equipment such as tanks back into service: they are not as effective as more modern vehicles, but they still increase Russia’s frontline firepower.

The economic situation

Ukraine’s economy contracted by almost 30 per cent in 2022. The IMF has forecast growth of 1-3 per cent in 2023; the World Bank is a little more optimistic, suggesting 3.5 per cent in 2023 and 4.0 per cent in 2024 (though the latter figure assumes that the war will be over by mid-2024 – which seems unlikely). Based on surveying businesses, the World Bank believes that 79 per cent are fully or partially open; the remainder are permanently or temporarily closed. Firms are also adapting to wartime conditions, making more use of IT and digitalisation and/or supplying new customers.

Russia’s economy is in better shape than Ukraine’s, helped by the high price of oil and gas.

Western sanctions have certainly affected some sectors of the Russian economy and its future growth prospects, and restricted the access of Russian firms to international markets. Western export controls have been reasonably effective in preventing Western high-tech components from reaching Russia, despite some circumvention. But overall, Russia’s economy is in better shape than Ukraine’s, helped by the high price of oil and gas since the crisis began. On a PPP basis, the Russian economy was more than ten times larger than the Ukrainian economy in 2022. Even if growth figures are somewhat distorted by the contribution of defence activity to GDP (as they are also for Ukraine), the IMF forecasts that Russia’s 2023 growth will be 2.2 per cent (following a contraction of 2.1 per cent in 2022), falling to 1.1 per cent in 2024.

Ukraine’s heavy industries, which are largely concentrated in the east of the country, have been particularly badly affected by the war. Exports fell by 67.5 per cent from 2021 to 2022.14 Major steel plants in Mariupol have been destroyed, and the export of steel from the remaining plants, which previously relied on sea transport, has been severely disrupted: transport by rail costs much more.

Despite the war, Ukraine will remain an agricultural powerhouse. Agriculture accounts for more than 10 per cent of its GDP. Though production dipped considerably in the ‘market year’ 2022-2023 (from September 1st 2022 to August 31st 2023), it is forecast to recover a little in market year 2023-2024. Nonetheless, the US Department of Agriculture predicts that maize production will be down by 18 per cent compared with the average for 2018-2022; wheat will be down by 16 per cent; sunflowers (of which Ukraine is the world’s largest producer) by 7 per cent.15

The EU’s cancellation of tariffs and tariff rate quotas on Ukrainian imports in June 2022 has also changed the pattern of Ukrainian trade: while Ukraine’s exports fell overall in 2022, the percentage going to the EU rose from 40 per cent in 2021 to 63 per cent. In 2023, Eurostat figures show that Ukraine accounts for a larger percentage of EU imports of some commodities, including maize and timber, than it did before the war. This growth in trade has not been universally welcomed in the EU, however: in April, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia unilaterally banned imports of some Ukrainian agricultural products, complaining that they were damaging their own agricultural sector. The European Commission was forced to step in and impose a short-term ban on the export of Ukrainian grain and other goods to the five countries, while still allowing goods to transit to other EU and non-EU destinations. When the Commission lifted the ban in September, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia imposed national bans, illegal under EU rules. The row is a reminder that even countries that in principle support Ukraine’s accession to the EU may have national interests to defend in the accession negotiations.

Whatever happens to its agricultural and other exports, Ukraine’s economy will take a long time to recover to anything like its pre-war size, and will continue to rely heavily on external assistance. So far, almost €140 billion has been pledged by the EU, the US, other states and various international financial institutions.16

Western politics: Ukraine fatigue and worse

Politics in the West, rather than anything that Ukraine is doing or not doing, mean that the prospects for future military and financial assistance are uncertain. Leaders who initially wanted to show solidarity with Ukraine are now sounding less committed: Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, under the impression that she was talking to the President of the African Union, told two Russian pranksters “We [are] near the moment in which everybody understands that we need a way out”.17 Among those who were never as enthusiastic about supporting Kyiv, or even leant towards Russia, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán recently met Putin in the margins of a summit in Beijing. His political director, Balázs Orbán, subsequently wrote on X (formerly Twitter) on October 26th that Western strategy in Ukraine did not work, and that the West needed a new strategy based on a ceasefire and peace talks. The Hungarian government is likely to receive support from the newly-elected prime minister of Slovakia, Robert Fico, who has already suspended military aid to Ukraine and called for “an immediate halt to military operations”.18

Only 41 per cent of American voters backed US military aid for Ukraine in October 2023.

Despite their rhetoric, Orbán and Fico did not block consensus on conclusions expressing support for Ukraine at the European Council meeting on October 26th and 27th: the EU reiterated that it would “continue to provide strong financial, economic, humanitarian, military and diplomatic support to Ukraine and its people for as long as it takes”, and even spoke of accelerating the delivery of military supplies including missiles, ammunition and air defence systems. In addition, EU leaders asked Borrell to consult with Ukraine on the Union’s future security commitments to it and to report back by the European Council’s December meeting – though it is unclear whether they want him to recommend that the EU continue, increase or decrease its military help or its military training for Ukrainian forces.19 But whatever rhetorical support the European Council offered in October, Fico and Orbán can still hold up concrete decisions on help for Ukraine in lower-profile ways if they choose to.

There has already been one example of such obstruction: the European Commission has proposed to create a ‘Ukraine facility’ worth €50 billion for the 2024-2027 period, as part of the mid-term review of the EU’s Multi-annual Financial Framework for 2021-2027. But the facility – a mixture of loans and grants – needs unanimous approval, and Orbán has said that he will reject the Commission’s proposals (though he might relent if the Commission releases some of the EU funds for Hungary that have been blocked over rule of law concerns). Fico’s position is less clear: he has described Ukraine as “one of the most corrupt countries in the world”, and called for additional measures to ensure that EU funds are not misappropriated, but has not said that he would block more aid for Kyiv.20 But Orbán and Fico are not the only obstacles to further assistance for Ukraine: Germany is reportedly among those blocking a proposal from Borrell to allocate €5 billion a year for four years in additional military assistance for Ukraine from the European Peace Facility.21

In the US also, there is growing opposition to further aid for Ukraine among right-wing Republicans in the House of Representatives and to a lesser extent in the Senate. Popular support for Ukraine is also shrinking: only 41 per cent of American voters backed US military aid for Ukraine in October 2023, compared with 35 per cent who opposed it (with the rest not sure). Only 35 per cent of Republican voters backed it, and even among Democrats the level of support fell from 61 per cent to 52 per cent between May and October 2023.22 Although the new Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, said after his election “we can’t allow Vladimir Putin to prevail in Ukraine because I don’t believe it would stop there”, earlier this year he voted against further aid to Kyiv.23 He has already rejected Joe Biden’s request to the US Congress for another $61.4 billion in funds for Ukraine, including $30 billion for military equipment and munitions, linked with more funding for Israel and for US border security.24 Johnson insisted that the request should be split up, with aid to Israel being voted on first. Even in the Biden administration, there are signs of impatience with Ukraine: unnamed US officials are saying that Ukraine only has until the end of this year or early 2024 “before more urgent discussions about peace negotiations should begin” – a far cry from frequent statements by Western leaders since Vladimir Putin launched his war of aggression that they would do “whatever it takes” to restore Ukraine’s sovereignty or stand with Ukraine “for as long as it takes”.25

It would be wrong to portray this tendency towards ‘Ukraine fatigue’ as universal, either in Europe or the US. The Baltic states continue to be among the leading supporters of Ukraine in terms of the percentage of their GDP going to military and other forms of aid: Lithuania (1.9 per cent), Estonia (1.8 per cent) and Latvia (1.6 per cent) rank first, second and fifth. By comparison, Germany (0.9 per cent), the UK (0.5 per cent) and the US (0.3 per cent) seem rather ungenerous, even though in absolute terms they have all given much more than their smaller partners. The Baltic states are now considering outreach to parts of the US where support for Ukraine seems to be flagging.26 In the US, many Republicans in the Senate, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, still support further aid for Ukraine, as do the vast majority of Democrats in both houses.

Putin can do much more lasting damage to European security than Hamas or even its Iranian allies could.

The conflict in the Middle East, however, has made it harder for backers of Ukraine to make their case – both because they are drowned out in the media by the new crisis, and because (particularly in the US) Ukraine-sceptics can suggest that Israel is a closer ally of the US than Ukraine is, and should therefore be prioritised when it comes to distributing limited stocks of weapons and munitions.

The conflict in the Middle East is without doubt a serious matter, with the potential to draw in other countries in the region and to spark social division and terrorism in Europe and beyond. While being realistic about its own influence, as Luigi Scazzieri has written recently, the EU should be involved in political and humanitarian efforts to improve the situation in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories.27 But European leaders need to remind themselves that Ukraine borders on four EU member-states, and is at war with Russia, a nuclear-armed neighbour that in turn shares borders with five more member-states, all of which were at one time parts of a Russian empire that Putin often harks back to in his speeches and writings. Putin can do much more lasting damage to European security than Hamas or even its Iranian allies could – though they can certainly cause serious problems, from destabilising other countries in the region to unsettling global oil markets by disrupting shipping in the Gulf. Putin will be the main beneficiary if the West turns its focus from Ukraine to Gaza. Both Ukraine and the Middle East need attention, but the steps European governments need to take to contribute to restoring stability in the latter case are very different from those needed to ensure that Putin does not profit from his attack on Ukraine.

A strategy and an action plan for Ukraine

Regardless of what is happening or may happen next year in US politics, the EU must take a more strategic approach to both the war in Ukraine and its aftermath. It should start by defining its aim with absolute clarity: 20 months into the war, the mantra of supporting Ukraine “for as long as it takes” is an inadequate framework for deciding what exactly needs to be done and what resources need to be committed to doing it. The EU should say unequivocally that its goal is Ukraine’s recovery of all its territory and its integration into the EU, not merely its survival in the parts of the country not occupied by Russia.

Borrell told the CER conference on October 24th that Putin was waiting for the West to get tired. The Union should disabuse Putin of the hope, encouraged by European politicians like Orbán and by various former US officials and figures in the Republican Party, that if he keeps fighting long enough the West will force Ukraine to cede some of its territory in order to get a ceasefire.28 Putin’s own public statements belie the idea that he would take an ‘off-ramp’ and make peace on terms that would leave Ukraine without some of its territory but otherwise fully sovereign if he were offered the chance. He repeatedly shows that he still rejects Ukrainian statehood, and remains confident that Russia can win a military victory.29

The Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015 in any case showed the futility of making territorial concessions and expecting Putin to stick to his side of the bargain. In its approach to the fighting between Israel and Hamas, the EU (after lengthy debates) has not called for a ceasefire, which would leave Hamas intact and able to regroup to launch further attacks in future. Instead, it has recognised Israel’s right to defend itself, within the limits set by international humanitarian law. The EU needs to take a similar line in Ukraine: any ceasefire or armistice that leaves Putin’s forces in a position to regroup and attack Ukraine again in a few years should be off the agenda.

On November 8th, the European Commission recommended the opening of accession negotiations with Ukraine (and Moldova), while noting a number of areas in which Ukraine still had work to do. Of the seven points set out by the Commission in June 2022 as conditions for candidate status, Ukraine has completed four (on the formation of the Constitutional Court, vetting and appointment of judges, anti-money laundering legislation and media law). Three more remain work in progress (on the fight against corruption, reducing oligarchic influence and protecting the rights of minorities), but the Commission has decided that Ukraine has done well enough to recommend the start of negotiations, even if there is still a long way to go to membership. European Council endorsement of this recommendation in December, leading to negotiations with Ukraine early in 2024, would be an important next step, showing lasting European commitment to Ukraine’s place in Europe.

This is the ideal moment for Europe to rationalise its fragmented defence industrial sector.

Ukrainians who follow the EU’s internal debates closely, however, are rightly worried that a Franco-German expert report on EU institutional reform, which was commissioned by the two governments, is being debated – though not universally welcomed – as a blueprint for future enlargements.30 While the report acknowledges that Ukraine and Moldova are now among the candidates for membership, it suggests that “the accession of countries with disputed territories with a country outside the EU will have to include a clause that those territories will only be able to join the EU if their inhabitants are willing to do so”. Such a formula would potentially force Ukraine (and other candidates such as Moldova and Georgia) to choose between keeping their territorial integrity but remaining outside the EU; and joining the EU but accepting effective partition – since Russia is hardly likely to allow the inhabitants of Crimea, the Donbas or other occupied areas to vote freely on joining the EU. In this scenario, if Ukraine insisted on its territorial integrity, it might be kept permanently in the European Political Community, envisaged by the Franco-German group as the outermost circle of European integration, for countries unwilling or unable to join the EU. Rather than forcing such a choice on Ukraine (and Georgia and Moldova), the EU should make clear that when Ukraine accedes, it will do so de jure in its entirety, as Cyprus did in 2004, regardless of whether any of its territory remains under (hopefully temporary) occupation.

In parallel with any political gestures, the EU needs to step up its military support for Ukraine. In his remarks at the CER conference on October 24th, Borrell rightly said “Ukrainians cannot defend themselves without our strong support”. Unlike the US, European states will not face competing claims on their stockpiles of weapons and ammunition from Israel. The problem is that European states, having under-invested in defence since the end of the Cold War, have limited stocks to give to Ukraine. Still, most do not have to worry about a surprise attack from a neighbour. They should be willing to tolerate a higher level of theoretical risk, and increase their transfers of weapons and munitions to Ukraine. The UK, for example, has supplied Ukraine with 14 Challenger 2 tanks out of a total of 227 (on paper, at least – some may not be serviceable). While the British Army needs to have enough tanks to fulfil its NATO commitments, the UK should work on the basis that contributing to Ukraine’s success on the battlefield also reduces the Russian conventional military threat to vulnerable NATO allies, particularly the Baltic states, and deliver as many tanks and as much ammunition for them as possible.

Europe does not need to put its entire economy on a war footing, but it has to do enough to ensure Russia’s defeat, and then to be able to offer Ukraine security commitments sufficient to deter any fresh aggression. That means not merely replacing equipment already supplied to Ukraine, but also investing in defence production for the long term – until the end of the war, and beyond, since it is likely that Russia under Putin or any likely successor will continue to harbour imperial ambitions. The EU and other European states need to provide a qualified workforce and a reliable pipeline of orders for European defence manufacturers. What they procure should strengthen their own defences and provide Ukraine with effective forces – the latter based on a limited number of equipment types, ideally those that have already proved their suitability for battlefield conditions in Ukraine. This is the ideal moment for Europe to rationalise its fragmented defence industrial sector.

At present, EU fiscal rules constitute an important obstacle to an increased European defence effort. The EU’s economic governance rules oblige member-states to keep their structural budget deficit below 0.5 per cent of GDP and their national debt below 60 per cent of GDP. However, these limits can be relaxed in response to “an unusual event” outside the control of the government concerned, which has a major impact on the public finances. Under current rules (which are in the process of revision), the European Commission is also responsible for deciding whether any given event justifies such a relaxation for the EU as a whole (the ‘General Escape Clause’). The Commission activated the General Escape Clause during the COVID-19 pandemic, and left it in place in 2022 because of the economic uncertainty caused by the war, but it wants to deactivate it by the end of this year.

The war, with its far-reaching consequences both for European security and the EU’s economic situation, is far from over, however, and seems on the face of it to be just the sort of unusual event that should be catered for. But Eurogroup president Paschal Donohoe told the Riga Conference on October 21st that though EU economies were “very much defined by war” at present, they were “not yet at the point where they could be defined fully as a wartime economy”. He made clear that while extra defence spending might be funded by issuing debt, the Commission would still want member-states to cut debt overall in order to reduce inflation and give confidence to the financial markets. In other words, if EU member-states boosted their defence spending, they would have to more than match the increase with higher taxes and/or lower spending on other things. If they did not, they would face being subject to fines under the Excessive Deficit Procedure, up to a maximum of 0.5 per cent of GDP – although such fines have never been applied in practice. The ongoing reform of the fiscal rules may reduce the size of the possible fines, thereby making it easier for the Commission to levy them in practice.

In current circumstances, the EU should be incentivising increased defence spending, not punishing it.

Member-states should put pressure on the Commission to treat the war as an “unusual event”. That seems to be the direction that the Spanish presidency of the Council of the EU would like to go in: it reportedly tabled a draft proposal for revisions to the EU’s economic governance rules that would give special treatment to investments in defence when deciding whether a government had breached the deficit limit.31 But it is far from clear that Spain will be able to find a consensus on such a carve-out from budgetary discipline.

In current circumstances, the EU should be incentivising increased defence spending, not punishing it. It could for example choose to exempt defence spending fully from the ‘expenditure path’ which is set to become the single operational indicator for finance ministers in the new fiscal framework. This is the growth rate of government spending, net of some factors like interest rate payments and unemployment spending. But this option would be less powerful than extending the escape clause, since increased defence spending would still translate into higher member-state deficits and debt levels, which could trigger possible enforcement action.

The Union could also do more to encourage public and private investment in the defence industrial sector, both by amending European Investment Bank rules that currently ban it from investing in “core defence” such as weapons or ammunition production, and by reinforcing Commission guidance clarifying that private investment in defence firms is compatible with EU rules on sustainable finance.

Beyond the war, the EU also needs to ensure that Ukraine can recover economically and that it is institutionally prepared for accession. The European Commission wants the Ukrainian government to come up with a vision for the future of the country’s economy – a challenge, in the midst of the war. Ukraine may be tempted to try to recreate the economy that it had before the war, and agriculture in particular seems likely to remain an important sector; but it may turn out that the best thing Ukraine can do is to find a new economic model, adapted to post-war conditions. It has considerable potential as a provider of green energy from wind, solar and hydropower. It has significant deposits of lithium (though many of these are in currently occupied territories, or near the front line) and was the world’s sixth largest producer of natural graphite in 2021 – both substances essential for making batteries for electric vehicles, and for which the West is currently heavily dependent on China.32 Ukraine’s digital sector has continued to grow and to export, even during war time: it accounted for 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2022, and IT exports grew from $3.2 billion in 2018 to more than $7.3 billion in 2022 – despite the impact of the war that year.

Not everything in the economy will change, however: some of the sectors that were important in the pre-war period are likely to remain vital in future. Ukraine had a significant defence sector, inherited from the Soviet Union, which has shown considerable resilience and the ability to innovate during the war, and is now attracting the interest of foreign investors. In October, the German defence manufacturer Rheinmetall announced the formation of a joint venture with the state-owned Ukrainian Defense Industry, with the intention of establishing joint production of armoured vehicles.33 Western governments should encourage more partnerships of this kind, both to meet the needs of the war and with a view to the longer-term defence needs of Europe, and the Commission should encourage Ukrainian participation in EU-backed defence projects.

The Commission is working on plans for recovery, growth and reform, but Ukraine will need enormous sums of money not merely for reconstruction, but to induce the 4 million or so Ukrainian refugees currently in the EU to go home and stay to contribute to its future development. There is a risk that post-war Ukraine might otherwise resemble post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina, where refugees initially returned in large numbers, with the population reaching 4.2 million in 2002 (having fallen from 4.5 million in 1991 to 3.8 million in 1995), only to fall again subsequently to 3.3 million by 2021, as many left the country again in search of economic opportunities.

It seems iniquitous to make Ukraine or its allies pay for the damage done by Russia.

In March 2023 the World Bank estimated that the cost of reconstruction would be $411 billion – more than twice Ukraine’s pre-war GDP of about $200 billion. Ukraine would struggle to finance such a sum, and in any case it seems iniquitous to make Ukraine or its Western allies pay for the damage done by Russia. Though there is considerable support from former Western officials and others for confiscating Russian state assets frozen by Western sanctions, amounting to about $300 billion, governments and the EU have so far moved cautiously.34 The Commission put forward initial proposals for using Russian assets to support Ukrainian recovery in November 2022, and almost a year later the European Council called on Borrell and the Commission to make proposals for a windfall tax on profits currently being made by European financial institutions from the sanctioned assets.

Belgium has already agreed to invest €1.7 billion from tax revenues on frozen Russian assets in Ukraine in 2024. But the Belgian move and the proposals requested by the European Council would leave the principal untouched, ready to be returned to Russia once the war was over; and it would yield a small fraction of what Ukraine needs. The EU should worry less that if it confiscates Russian state assets this will encourage other countries to sell off euro-denominated assets, and more that the alternative to using Russia’s money is for Western tax-payers and impoverished Ukrainians to bear the cost. If outright confiscation is still considered too legally and politically problematic, there may be other ways of achieving the same objective, such as swapping frozen assets for Ukrainian ‘restitution bonds’, giving Ukraine immediate access to funds while giving Russia the chance to recover the principal as part of a peace settlement.35

Conclusion

Within days of Russia’s all-out attack, von der Leyen had described Ukraine as “one of us”. After 30 years of refusing to say definitively that Ukraine was a European state, and therefore entitled to apply for EU membership according to the Treaty on European Union, in June 2022 the EU accepted Ukraine as a candidate country. At the Vilnius summit in July 2023, NATO members stated “Ukraine’s future is in NATO” (though without setting a target date for it to join). Now the chatter in Brussels and Washington suggests that some members of the EU and NATO are wondering whether they can quietly forget such statements.

Rhetorical commitment to Ukraine is easy; helping Ukraine to re-establish control of its territory and then supporting its long-term recovery and integration into Western institutions is much harder. The consequences of failing to give Ukraine the military and economic aid it needs to drive Russia out of its territory, however, would be worse. Putin would be encouraged in his irredentist aims, increasing the threat to other countries formerly under Russian or Soviet domination. The EU and NATO will look weak and their security umbrella unreliable if they first offer membership to a country, and then appear to back away when it has to deal with a large-scale, long-term military threat. The West’s adversaries may use this either to destabilise further Western partners, or to attract countries to their camp by showing that they will always defend their allies – as Iran and Russia have done in Syria, for example.

Other countries may conclude that Ukraine’s mistake was to give up the nuclear weapons stationed on its territory when the Soviet Union collapsed. The security assurances Ukraine received in return from Russia, the UK and the US turned out to be worthless, but at least the UK and US are now providing weapons and training for Ukraine. If even that support was cut off, other countries under threat from their neighbours might follow the example of Israel and develop their own nuclear deterrents, further undermining the global nuclear non-proliferation regime.

Finally, there is the effect on Ukraine itself. Since 2014 Ukrainians have been dying for the right to choose a European future, but without increased Western support they may end up stuck in the grey zone between the West and Russia, impoverished, vulnerable to future Russian attacks or political subversion, and embittered. The domestic politics of accepting the loss of the 17 per cent of the country that is currently occupied could be very destabilising, leading to the rise of extreme nationalist organisations; the largely mythical ‘neo-Nazis’ that Putin claims currently rule Ukraine might become a reality. That would not be a recipe for peace in Central and Eastern Europe.

Since Russia does not want to give up the fight, and Ukraine cannot do so if it wants to remain an independent state, this war is likely to be a long one. To that extent, Borrell was probably wrong to fear that Ukraine would surrender quickly if the West withdrew its support. But he was right to worry that Ukraine would not be the last country in Putin’s sights. The time for Europe to act and increase its capacity to support Ukraine militarily for the longer term is now, while US help for Ukraine continues to flow and Ukraine is still making incremental progress in the war.

If Biden is re-elected, US support will probably continue, but at a lower level. Ukraine will be able to hold out, even if it can only make limited progress towards victory. But if Europe does nothing until the US election, Trump is elected and US aid ends abruptly, then the situation will be much worse. Ukraine will fight on, because it has no choice; some Western countries will probably keep supplying it under any circumstances; but Russia will be able to make further territorial gains. It could not easily capture the whole country, or even completely control all the territory it occupies, but over the next few years it could change the map of Europe. Whatever diplomatic efforts European leaders feel they have to make in the Middle East, therefore, they must also urgently increase their efforts to ensure that Putin does not prevail in Ukraine. The cost of helping Ukraine is high; the cost of not helping it will be higher.

2: Valeriy Zaluzhnyy, ‘Modern positional warfare and how to win in it’, The Economist, November 1st 2023.

3: Philipp Ueffing and others, ‘Ukraine’s population future after the Russian invasion – The role of migration for demographic change’, EU Publications Office, 2023; Olena Harmash, ‘Ukrainian refugees: How will the economy recover with a diminished population?’, Reuters, July 7th 2023.

4: Aleksander Palikot, ‘Amid corruption scandals and mounting problems, Ukraine vows to shake up the military enlistment system. It’s a tough task’, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, August 18th 2023; Simon Shuster, ‘”Nobody believes in our victory like I do”. Inside Volodymyr Zelensky’s struggle to keep Ukraine in the fight', Time, November 1st 2023.

5: Andrew Roth, ‘Battlefield deaths in Ukraine have risen sharply this year, say US officials‘, The Guardian, August 18th 2023.

6: Christoph Trebesch and others, ‘The Ukraine support Ttracker: Which countries help Ukraine and how?’, Kiel Working Paper No 2218, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, 2023.

7: Lolita Baldor, ‘Ukraine uses US-provided long-range ATACMS missiles against Russian forces for the first time’, Associated Press, October 17th 2023.

8: Barack Ravid, ‘Scoop: US to send Israel artillery shells initially destined for Ukraine’, Axios, October 19th 2023.

9: Francis Tusa, ‘Ammunition, ammunition, ammunition, and ‘things that go bang’’, Defence Analysis, March 23rd 2023.

10: Noah Robertson, ‘Production of key munition years ahead of schedule, Pentagon says’, Defense News, September 15th 2023.

11: Benoît Vitkine, ‘Russia plans to increase its military budget by 70 per cent in 2024’, Le Monde, September 26th 2023.

12: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘Is European defence missing its moment?’, CER insight, January 16th 2023.

13: ‘Macron calls for French budget defence boost in "war economy"', France 24, June 13th 2022.

14: Svitlana Taran, ‘EU-Ukraine wartime trade: Overcoming difficulties, forging a European path’, European Policy Centre discussion paper, August 21st 2023.

15: International Production Assessment Division, Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture, Ukraine country summary.

16: Christoph Trebesch and others, ‘The Ukraine support tracker: Which countries help Ukraine and how?’, Kiel Working Paper No 2218, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, 2023.

17: Veronika Melkozerova and Hannah Roberts, ‘Europe can’t afford to get war fatigue, Ukrainians tell Meloni’, Politico, November 3rd 2023.

18: Nicolas Camut, ‘Slovakia’s Fico announces halt of military aid to Ukraine’, Politico, October 26th 2023.

19: General Secretariat of the Council, ‘European Council meeting (26 and 27 October 2023) – Conclusions’, October 27th 2023.

20: Jorge Liboreiro, ‘Orbán opposes the EU’s €50-billion support plan for Ukraine, while Fico raises corruption concerns’, euronews, October 27th 2023.

21: Andrew Gray, ‘EU’s 20 billion euro plan for Ukraine military aid hits resistance’, Reuters, November 13th 2023.

22: Jason Lange and Patricia Zengerle, ‘US public support declines for arming Ukraine, Reuters/Ipsos poll shows’, Reuters, October 5th 2023.

23: ‘Mike Johnson Gives First Interview After Being Elected House Speaker’, transcript by Rev.com of Sean Hannity interview with Mike Johnson, October 30th 2023.

24: Tami Luhby, ‘US aid to Israel and Ukraine: Here’s what’s in the $105 billion national security package Biden requested’, CNN, October 20th 2023.

25: Courtney Kube, Carol Lee and Kristen Welker, ‘US, European officials broach topic of peace negotiations with Ukraine, sources say’, NBC News website, November 3rd 2023; Crispian Balmer and Giuseppe Fonte, ‘Italy’s Draghi promises “whatever it takes” to restore Ukrainian sovereignty’, Reuters, February 24th 2022; Barbara Moens, ‘Von der Leyen applauds Kyiv’s ‘excellent progress’ ahead of EU enlargement decision’, Politico, November 4th 2023.

26: Gabriel Gavin, Jacopo Barigazzi and Eric Bazail-Eimil, ‘Ukraine’s allies plan US charm offensive’, Politico, October 30th 2023.

27: Luigi Scazzieri, ‘Europe and the Gaza conflict’, CER insight, October 20th 2023.

28: Josh Lederman, ‘Former US officials have held secret Ukraine talks with prominent Russians’, NBC News, July 6th 2023.

29: See, for example, ‘Meeting with members of the Civic Chamber’, Kremlin website, November 3rd 2023.

30: Olivier Costa, Daniela Schwarzer (rapporteurs) and others, ‘Sailing on high seas: Reforming and enlarging the EU for the 21st century’, report of the Franco-German working group on EU institutional reform, September 18th 2023.

31: Aurélie Pugnet and János Allenbach-Ammann, ‘Defence spending could get special status in new EU deficit rules’, Euractiv, November 8th 2023.

32: Anthony Barich, ‘Ukraine aims to become major graphite supplier – when the war ends’, S&P Global Market Intelligence, May 10th 2022.

33: ‘Rheinmetall AG and Ukrainian Defense Industry JSC establish joint venture in Kyiv’, Rheinmetall press release, October 24th 2023.

34: See for example ‘Why and How the West Should Seize Russia’s Sovereign Assets to Help Rebuild Ukraine’, Working Group Paper No 15 of the International Working Group on Russian Sanctions, September 4th 2023.

35: Timothy Ash and Ian Bond, ‘Why Russia must pay for the damage it has done – and how to ensure it does’, CER insight, June 19th 2023.

Ian Bond is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2023

View press release

Download full publication