To be influential in the EU, Spain must rebuild its political centre

Spain’s inconclusive electoral results will diminish Madrid’s influence in Europe. As holder of the EU’s rotating presidency, Spain will be diligent but distracted. Conservatives and socialists should work to rebuild the centre.

Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez surprised many when he decided to call a snap election after the poor performance of his Socialist Party (PSOE) in May’s regional elections. But he himself was probably surprised by the results of the general election, held on July 23rd. Sánchez expected to be defeated and hoped that a quick campaign would minimise his losses. Opposition leader Alberto Núñez-Feijóo was poised to be Spain’s next prime minister, with his Conservative Party (PP) winning comfortably. As the campaign went on, though, it became clear that Sánchez was not going to lose as badly as many initially expected; and Feijóo’s road to Spain’s prime-ministerial La Moncloa palace was not going to be as smooth as the polls predicted.

All pre-election projections put PP consistently ahead, and assumed that Feijóo would be able to govern with the support of the far-right Vox. PSOE, which is in coalition with the far-left Podemos, was projected to lose as many as 20 of its 120 seats in Spain’s 350-seat parliament. But the Conservatives and Vox collectively failed to score enough votes to form a government. Feijóo hoped he could either gain enough seats to try to form a minority government, or to enter into a supply and confidence agreement, or even a coalition, with Vox. For that, he needed Vox to perform quite well. But contrary to lazy headlines, Vox was not on the rise in Spain. The polls predicted it would lose about 21 of its current 52 seats. It ended up losing 19 seats.

To become prime minister, Feijóo also needed PSOE and its junior partner, the newly created Sumar, to do badly. His strategy backfired. Spain’s rushed electoral campaign was Feijóo’s to lose – and he lost it. While PP obtained the most seats (with 137, up from 89), PSOE’s surprisingly good results (121 seats, up from 120) make it almost impossible for Feijóo to become prime minister (see Chart 1). Feijóo only has a route to power if Sánchez fails to gather enough support for his own bid and agrees not to block Feijóo’s attempt at forming government – and the latter will not happen. Sánchez, by contrast, could find enough backing for a second term with the support of a collection of smaller parties. But negotiations with these mostly regional parties will not be easy. If they fail, Spaniards could be heading to the polls again this winter.

Spain’s King Felipe VI now has the unenviable task of appointing the candidate with the best chance of finding enough votes in parliament to become prime minister. There is no official deadline for the King to appoint a candidate, but he is expected to try after all the MPs have been sworn in, which must happen by August 17th. A candidate has two attempts. At the first, they need an absolute majority of members of parliament to vote for them. If they fail, they can try one more time, 48 hours later. This time, to be successful, the candidate only needs a simple majority of those voting, regardless of any abstentions. If that fails too, politicians have two months to find an alternative candidate – or else the King will dissolve parliament and call for new elections, which must be held within 54 days.

Both Feijóo and Sánchez suffered from their choices of partner. But Sánchez knew better than to draw too much attention to the difficult dynamics of his partnerships. Sánchez’s allies include convicted terrorist Arnaldo Otegui, Oriol Junqueras, convicted of insurrection and embezzlement for his leading role in Catalonia’s 2017 unilateral independence bid (and later pardoned by Sánchez) and Equality Minister Irene Montero, a polarising Podemos leader that almost caused the collapse of Sánchez’s coalition earlier this year. Feijóo, however, was not so lucky. Over the course of the campaign, Vox became a prominent thorn in the Conservatives side. The snap election was intentionally timed to catch PP in the middle of intricate negotiations to form government with Vox in several Spanish regions, revealing difficult trade-offs in the process that Feijóo handled poorly.

At some point during the campaign, Vox, whose rise to power in 2018 owes more to a backlash against Catalonia’s failed independence bid than it does to traditional far-right ideas on equality, migration and Europe, decided to switch gears. Vox’s more radical wing moved away from voter-friendly messages on law and order and national unity to an outdated mish-mash of anti-everything policies that Spain’s rather progressive society would never rally behind. Vox’s move – and Feijóo’s refusal to unequivocally call it out – mobilised large numbers of previously unenthusiastic Spaniards, alarmed by the prospect of a far-right party getting close to power or even entering government.

Vox's rise to power in 2018 owes more to a backlash against Catalonia's failed independence bid than it does to traditional far-right ideas on equality, migration and Europe.

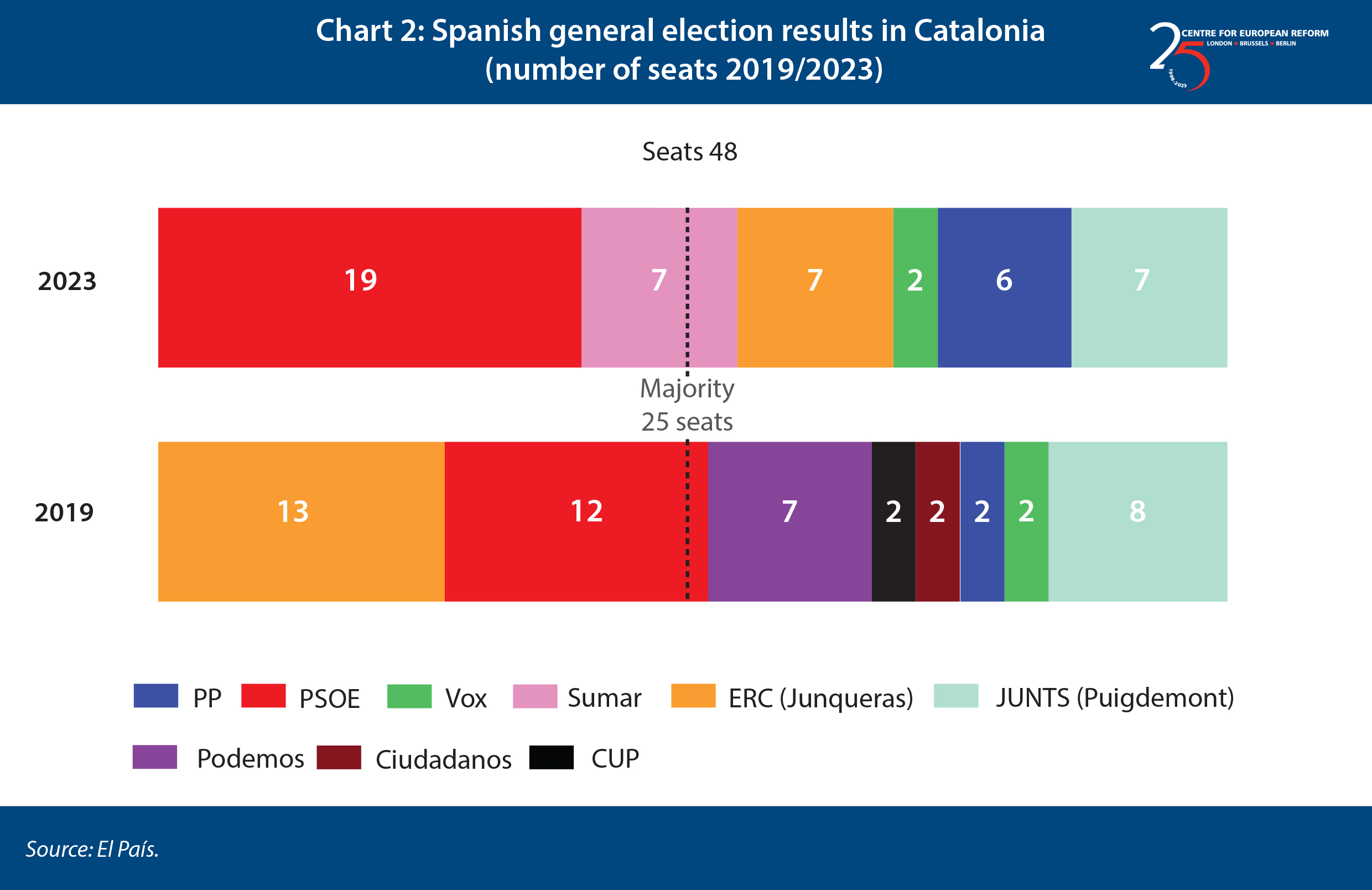

Sánchez’s own trade-offs may have been less salient during the campaign, but they will become more obvious if he tries to form government. Unlike in 2019, Sánchez will only have enough votes to become prime minister if fugitive Catalan independence leader Carles Puigdemont’s party agreees to make him prime minister. On July 5th the European Court of Justice refused to grant parliamentary immunity to Puigdemont – who is an MEP and lives in Belgium. On July 24th, Spain’s public prosecutor requested that a suspended European Arrest Warrant against Puigdemont be reactivated. One of Sánchez’s more daring political gambles has been to pardon all jailed Catalan political leaders and to change the criminal code so that some of the offences they were tried for, following riots and Puidgemont’s unilateral declaration of independence, have disappeared. His hope was to undermine support for the region’s most radical pro-independence parties. Given that PSOE and Sumar have managed to win almost half of the vote in Catalonia, overtaking Puigdemont’s and Junqueras’ parties, this strategy seems to have paid off (see Chart 2). But it would be politically and legally difficult for Sánchez to go further, and agree to Puigdemont’s demands for both a pardon and a referendum on independence in Catalonia.

Like many other European countries, Spain’s political travails have less to do with the rise – or fall – of a single party than they do with the collapse of the centre and the polarisation of previously mainstream parties on the centre-right and the centre-left. Since Spain’s long-running two-party system foundered in 2015 when newcomers far-left Podemos and liberal Ciudadanos entered parliament, the country has had to deal with fragile coalitions, unstable governments and repeated elections. In 2015 and 2016, Spaniards went to the polls three times. PP’s Mariano Rajoy eventually managed to secure a second term as prime minister in 2016, only to be ousted in 2018 by a motion of no confidence led by Sánchez. Sánchez then went on to win an election, narrowly, in 2019. He now has a decent chance of forming government again, but his tenure will probably be short because of disagreements between his potential partners.

Like many other European countries, Spain's political travails have less to do with the rise – or fall – of a single party than they do with the collapse of the centre and the polarisation of previously mainstream parties on the centre-right and the centre-left.

Sánchez’s concessions to both far-left Podemos and Catalan independence leaders, and his confrontational style have made him a polarising figure at home, despite his good record on economic and foreign policy. He rather skilfully kept his government together throughout Covid, the war in Ukraine and the cost-of-living crisis – but at the expense of tilting his social-democratic party to more extreme positions to please his partners. For its part, the PP’s cosiness with Vox and the popularity of PP’s radical Madrid president, Isabel Díaz-Ayuso, have shifted the party towards harder positions on climate scepticism, austerity for public services and opposition to wider wealth redistribution. Both PP and PSOE are likely to become more, and not less, radicalised – as more moderate voices inside and more moderate allies outside have all but disappeared. After a bruising campaign, there is little prospect for a grand coalition.

A clear election outcome in Spain would have been relatively inconsequential for the EU, even with Vox in government. Madrid’s fiercely pro-European views were unlikely to change much in the short to medium term and Vox would never have had enough seats to wield much influence over Feijóo’s approach to Europe.

Spain’s uncritical pro-European views may change with time, as the EU becomes more powerful and more ingrained into citizens’ lives. But this is not likely to result from more radical parties of the right or left entering government. It is more likely to happen through mainstream political parties becoming more critical of the EU, as the Union gets less technocratic and more political; or because of external shocks that disproportionately impact Spain, such as a new migration or financial crisis.

Spain's uncritical pro-European views may change with time, as the EU becomes more powerful and more ingrained into citizens' lives, not because of Vox or Podemos being in government.

The current inconclusive scenario will have an impact on Madrid’s place in the EU, however. Spain holds the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU until end-December. The presidency will be fine: both the Spanish government and Spain’s civil servants have been scrupulous in preparing it and will run it with diligence. A caretaker Belgian government successfully ran the country’s rotating presidency in 2010. The EU will also continue to function – the rotating presidency is a relatively modest responsibility and it was unlikely that Spain’s priorities would have had a big impact on important EU matters anyway. Since 2009, countries holding the rotating presidency work in teams of three called ‘trios’. Each trio agrees on presidency priorities and programmes months or sometimes years in advance. The Council of Ministers can intervene if a presidency goes awry. And other member-states can help the incumbent country should the need arise. The system is designed to withstand political turmoil – in 2022, France successfully held its presidency amidst an election campaign; and the far right entered government in Sweden two months before Stockholm took over the rotating presidency in January 2023.

Even though there is no way for Vox to enter government and Sánchez’s most unsavoury potential partners will not be able to cause much trouble to the presidency, negotiations to form a government will take time. If no party manages to form a government, new elections will happen before the end of the year. This would mean the current government running the entire presidency, but in an acting capacity. This would be bad for Madrid, which had hoped to shine during its presidency and has been trying to be more assertive in Europe. It would also bad for the EU: Spain will be distracted for the next few months, when the Union will be having serious discussions on enlargement, migration, institutional reforms, fiscal rules and China amongst other things. With Berlin too preoccupied with coalition infighting, Warsaw at loggerheads with Brussels, and Rome’s far-right government still trying to find its feet in Europe, European debates have been mostly dominated by Paris and Commission president Ursula von der Leyen. Both Covid and the war in Ukraine have made the Union more multipolar. The EU needs as many viewpoints as possible to help it navigate a more divided world.

The elections have put the spotlight on Spain’s most insidious flaw – a perpetual disagreement over national identity. Spain’s identity crisis permeates the country’s political system, which is often hostage to regionalist interests and has little space for centrist parties even though most Spaniards favour moderate positions. It also limits Spain’s own role in the EU. A country with unresolved identity issues cannot aspire to play a bigger role in Europe, let alone to lead it. Sánchez and Feijóo, or whoever comes next, agree with each other more than they agree with their intended coalition partners. A grand coalition may be a distant prospect. But a minority government of one of those parties with the support of the other would be better for Spain’s interests at home and abroad, at least until Spain can rebuild its lost political centre.

Camino Mortera-Martínez is head of the Brussels office at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment