Has the IMF’s lending become too expensive for its own good? The case for a lending rate cap

- Global economic growth is weak, and many countries have limited or no access to market financing. The World Bank estimates that 60 per cent of low-income countries are heavily indebted and at high risk of debt distress, while many middle-income countries also face significant budgetary challenges.

- The International Monetary Fund (IMF/Fund) is struggling to provide financing to countries that cannot pay their creditors. These countries often need a debt restructuring to cut their debt load and give the IMF’s traditional bailout programmes a fighting chance at restoring economic stability. But intransigent Chinese creditors, whose rise has diminished the importance of the Western creditors, are making these debt restructurings harder. And they also compete with the IMF to provide new lending: countries in debt distress are increasingly turning instead to bilateral creditors, especially China, for bailouts.

- To tackle the inflation surge that followed the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine, the world’s major Western central banks have swiftly increased interest rates. The IMF’s main lending rate consists of a fixed margin plus the interest rate on its ‘Special Drawing Rights’ (SDRi), derived from the prevailing interest rates of the five currencies that together make up the SDR basket – the dollar, euro, yen, renminbi, and pound sterling. Central bank hikes have therefore also sharply driven up the costs of borrowing from the IMF, which can currently be up to 8 per cent, probably discouraging countries from turning to the IMF.

- The Fund’s higher lending rates also means the Fund is a drag on debtor countries. In some cases, the burden of paying high interest rates to the IMF is worsening rather than alleviating countries’ budgetary woes and hampering their prospects of economic recovery.

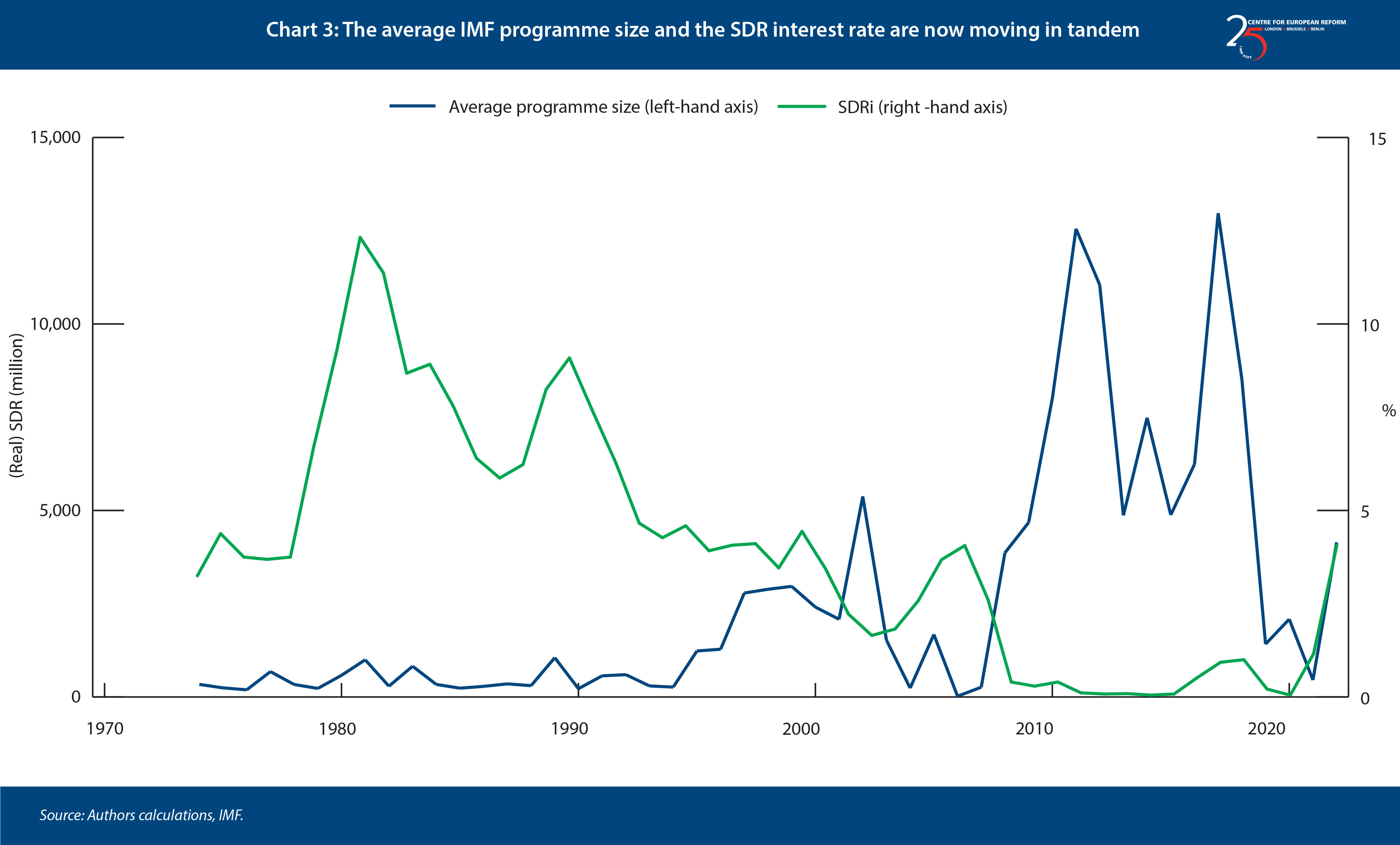

- Over the past 50 years, large volumes of IMF financial assistance have tended to coincide with a loosening of global monetary conditions. This led to a decline in the cost of IMF loans in periods when many member countries used the Fund’s financing. But, for the first time in its history, the IMF is increasing its overall financial assistance to its membership while its lending rate is rising.

- Rich creditor countries, including the US, the EU, the UK, and Japan, have a stake in defending the multilateral system of economic governance they built and should find ways to keep the IMF’s programmes viable in this new environment.

- Proposals to reduce IMF surcharges - levies on borrowed amounts which are meant to nudge member-states to repay large bailouts quickly and discourage them from borrowing too much - would not address this challenge. Reducing surcharges would only benefit a few of the countries most indebted to the Fund and may jeopardise the Fund’s ability to build up its own reserves, protect its balance sheet, and take risks to protect the global economy.

- The West and its allies should take the initiative to limit the rise in IMF lending rates by introducing a temporary cap on its key component: the SDRi. There is a precedent: in 2014, the IMF introduced a floor to prevent the SDRi from turning negative during a period when central banks were pushing interest rates down aggressively. An SDRi ceiling would also not affect the Fund’s own income model: the costs would be borne by the IMF’s creditor countries in the form of lower returns on their foreign reserve assets.

- An SDRi cap would help to prevent the Fund’s lending activities from becoming prohibitively expensive at a time of multiple shocks to the global economy. It would make the way in which SDR interest rate proceeds are redistributed from debtor countries to creditor countries less regressive. And reducing lending rates would discourage debtor countries from relying on opaque funding from bilateral creditors which, unlike the IMF’s programmes, is often about gaining political leverage, not restoring economic stability. All this would help to protect the IMF’s role as the only global lender of last resort that, while still dominated by the West, is owned by the entire world.

The UN recently warned that 52 countries – encompassing almost 40 per cent of the developing world – are in serious debt trouble.1 But the IMF is struggling to roll out its traditional bailout programmes to countries in economic turmoil. For one, the debt restructurings that often precede them are getting stuck in creditor disagreements and geopolitical rifts. Compared to the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, in which Western finance was dominant, there is now a wider set of creditors, especially China, and many of them are more reluctant to take losses on their claims.2 China massively expanded lending to developing countries as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), for example, but Beijing has refused to align with the Paris Club, the informal group of Western creditors that historically co-ordinated debt restructurings. In 2020, the G20 reached an accord with creditors including China on the ‘Common Framework’, which laid down a process for co-ordinating the restructuring low-income countries’ debts. Its results, however, have been disappointing so far.3

Another challenge to the IMF is that bilateral creditors are providing alternative bailout lending to low- and middle-income countries, possibly in exchange for political concessions or resources. China’s overseas bailouts are growing fast, and correspond to 20 per cent of total IMF lending over the past decade.4 Some research suggests that for every 1 per cent of GDP a country borrows from China, it becomes 6 per cent less likely to reach a deal with the IMF.5

In this period of low global economic growth and high interest rates, the IMF’s lending activities now risk becoming ‘procyclical’ for debtor countries, as the burden of repaying high interest rates to the IMF itself could lead to worse economic outcomes. Central banks around the world have tightened monetary conditions to rein in the inflation stoked by Russia’s war on Ukraine and the pandemic. This has led to a sharp increase in the cost of borrowing from the Fund, which can currently be as high as 8 per cent. The IMF’s basic rate of charge is comprised of a fixed margin of 1 per cent plus the ‘special drawing rights’ interest rate (SDRi). This SDRi is derived from the money market interest rates of the five currencies that together make up the SDR basket. The dollar and, to a lesser degree, the euro make up the largest share of the basket. And the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank have rapidly raised interest rates.

High lending costs make it harder for the IMF to fulfil its role as the multilateral lender of last resort to countries, both for existing debtors and countries that potentially need IMF support. The stakes are high. As a proportion of global GDP, the Fund’s outstanding credit is already close to a level last seen in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, even though the IMF’s balance sheet has become proportionally smaller as the world economy grew. Some of this rise in lending took the form of emergency loans, not traditional bailouts that can restore debt sustainability. For example, during the pandemic the Fund has approved an unprecedented number of requests for assistance under its emergency facilities – the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) and Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) – and temporarily doubled the amount that can be borrowed from these facilities.6 The IMF has also increased access to its regular lending arrangements. At the end of August 2023, ‘non-concessional’ outstanding debt - which is unsubsidised and subject to market-based interest rates - amounted to $130 billion, with 54 countries owing money.7 But the Fund could lend out more: a sizeable portion of its $1 trillion lending capacity remains untapped, and its regular loan book is growing slowly compared to the many countries that might need bailouts.

The multiple challenges the IMF faces are difficult to resolve in an environment of heightened geopolitical tensions. But those same tensions also mean the IMF remains by far the best placed institution to help countries in debt distress, because its multilateral character puts the national interests of creditor governments at arm’s length. The IMF should therefore consider introducing a temporary ceiling on its main interest rate – the SDRi – to prevent the Fund’s lending from becoming prohibitively expensive.

How much does the IMF charge for its loans?

IMF members can request loans through the Fund’s General Resources Account (GRA). These loans have costs. The first component is an interest rate, the basic rate of charge, which consists of a market-determined ‘Special Drawing Rights’ (SDR) interest rate – the SDRi – plus a fixed margin (currently 1 per cent).8 The SDR is an accounting unit for IMF transactions with member countries and an asset in countries’ international reserves. It is valued against a basket of five major currencies (the dollar, euro, renminbi, yen, and pound sterling) and can be swapped for those currencies if needed. The fixed margin is used to cover the operational costs of the IMF and support its various activities, including those related to providing policy advice and capacity development to member countries.9

The bulk of IMF borrowing costs stem from the SDRi – a variable rate redistributed to the IMF’s creditor countries.

The GRA can be thought of as a closed system of pooled international reserves where debtor countries pay, and creditor countries receive, the SDRi on their respective net balances. The financial flows resulting from the SDRi payments are therefore not part of the IMF’s own operational income but rather represent a direct creditor-debtor redistribution between its shareholders. The SDRi itself is a weighted average of certain interest rates in the five major reserve currencies.

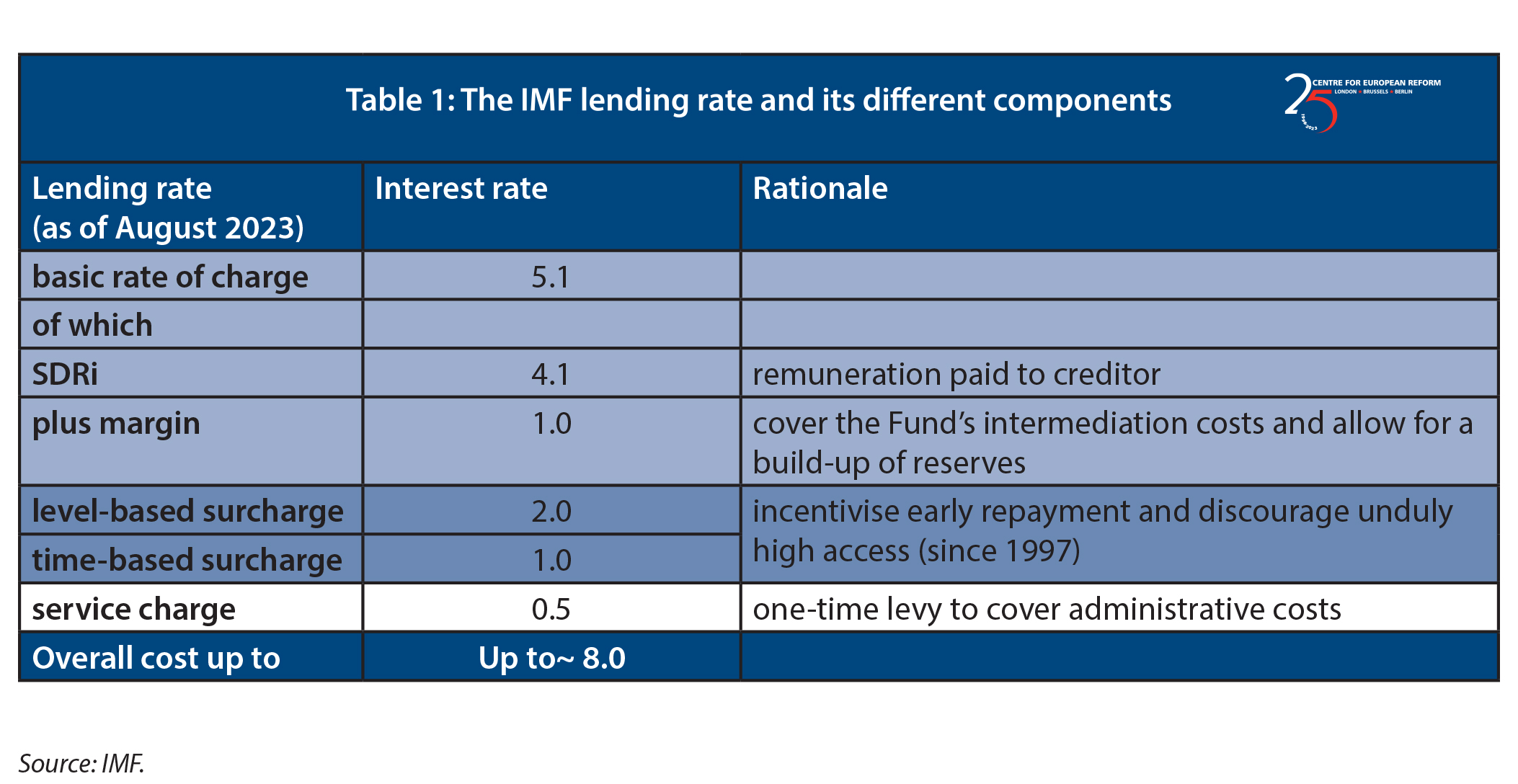

In addition to the interest rate, countries sometimes must pay surcharges for drawing on IMF resources. These surcharges are designed to prevent countries using GRA resources excessively or for too long.10 Each member of the IMF is assigned a quota, based broadly on its relative size in the world economy, which determines how much a member must provide to the IMF and how much it can borrow. Two types of surcharges exist: The first one is based on the size of the loans. This surcharge of 2 per cent is applied on the portion of GRA credit outstanding that is greater than 187.5 per cent of the member’s IMF quota. The second ‘time-based’ surcharge levies an additional 1 per cent for any credit exceeding the 187.5 per cent threshold for more than 36 months (for borrowing under a Stand-By Arrangement, which is intended to be short-term financial assistance) and 51 months (in case of borrowing under the Extended Fund Facility, which is more medium-term lending). In total, countries that owe more than 187.5 per cent of their quota could be charged a maximum of 3 per cent on top of the SDRi and fixed margin rates.

Surcharges represent a direct source of income for the Fund and help the IMF to build its own reserves (which are called Precautionary Balances), given that the fixed margin of 1 per cent already covers (most of) the IMF’s operational costs. In fact, with slightly more than 50 per cent of income from its lending activities last year, surcharges typically account for the bulk of the IMF’s operational income.11

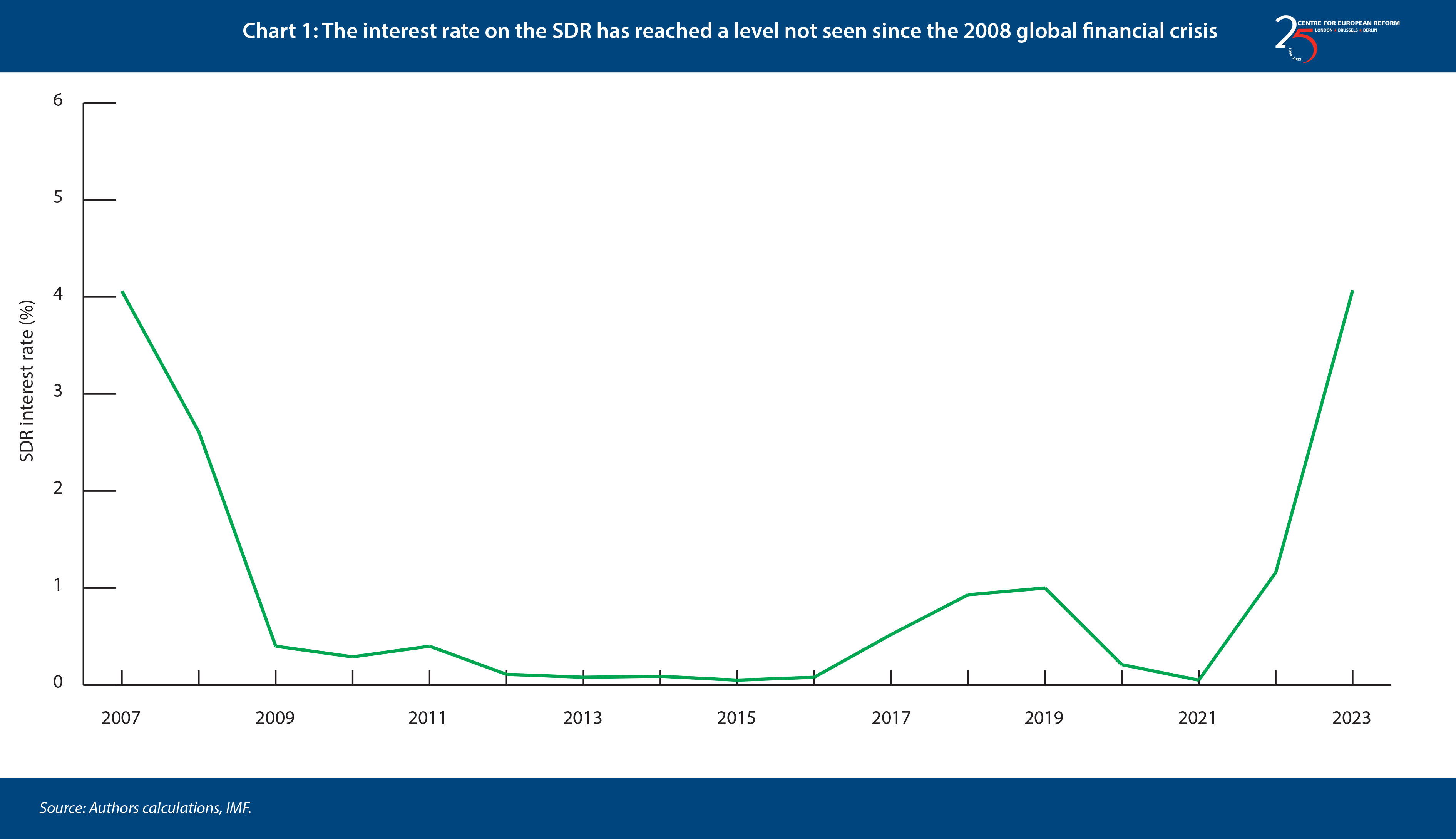

Table 1 provides an overview of costs of borrowing from the Fund, as of end-August 2023. As can be seen, currently the cost of borrowing from the GRA could amount to 8 per cent, depending on the amount borrowed and how long it is borrowed for (which determines whether surcharges are levied). Half of the borrowing costs stem, however, from the SDRi. As shown in Chart 1, the SDRi has increased sharply since Russia started its invasion of Ukraine and has reached a level not seen since the 2008 financial crisis. Given that central banks have telegraphed that they aim to keep rates high for a while and may even raise rates further if inflation does not come down sufficiently, a decline in the SDRi does not seem imminent.

In addition to the basic rate of charge and the surcharges displayed in Table 1, borrowing countries also must pay a small commitment fee and a service charge. The commitment fee is applied to the undisbursed portion of a loan and can amount to up to 0.6 per cent depending on the size of the amount committed (the maximum of 0.6 per cent is applied to amounts exceeding 575 per cent of the member country’s quota). Commitment fees are refunded to the borrowing member, in proportion to the drawings made. If a country draws the entire amount, the fee is fully refunded. The service charge is a fixed, one-off charge on each amount drawn from the GRA and currently stands at 0.5 per cent.12 However, compared to the basic rate of charge and the surcharges, the service charge is negligible. This is further illustrated by the fact that the respective income from service charges only accounted for about 4 per cent of the IMF’s total lending income in the last year.

IMF lending terms are procyclical for the first time

Because of the increase in the SDRi, countries in financial distress must borrow from the IMF at high interest rates. As a result, the IMF’s surcharges have recently been subject to intense debate.13 The fear is that surcharges contribute to a lending rate that is too high for the IMF to effectively act as global lender of last resort and is a ‘procyclical’ drag on debtor countries. In a period of stagflation – high inflation and weak economic activity – high Fund borrowing costs mean their lending can become more of a burden than a help. And surcharges tend to affect crisis-prone middle-income countries, with quotas that have not kept pace with their share of the world economy, and which need both extensive IMF financing and long periods to repay. These countries are faced with high surcharges exactly when they lack the ability to access other sources of financing.

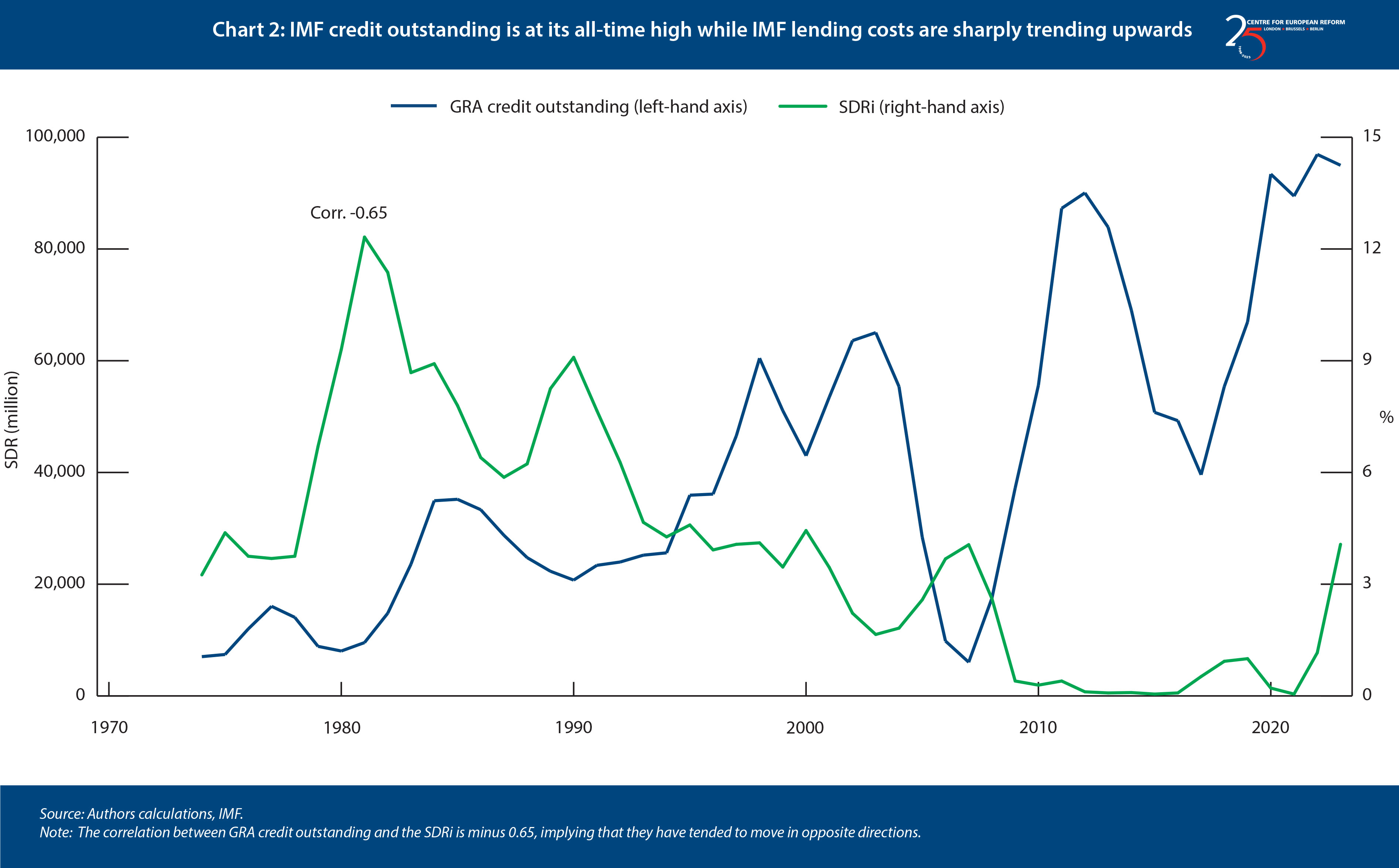

The big rise in IMF lending alongside rising costs of borrowing is unprecedented since the inception of the Fund.

There have been numerous calls for a broader reform of the IMF’s surcharge framework and a (temporary) suspension of surcharges in the wake of the pandemic and the Russian war on Ukraine.14 Sceptics counter that surcharges represent an important part of the IMF’s income model and are designed to set the right incentives to ensure a temporary and limited use of Fund resources.15 A reduction of surcharges would mainly benefit the largest five borrowers (Argentina, Egypt, Ukraine, Pakistan, and Ecuador) who together account for above 90 per cent of total surcharge income.

But the focus on surcharges is misguided. In contrast to surcharges, which are only paid by a few borrowing countries and have not changed as global interest rates have risen, the basic rate of charge currently accounts for the lion’s share of overall costs of borrowing from the Fund (see Table 1). As explained above, this is because major central banks have increased interest rates, in turn increasing the SDRi. The IMF’s lending now risks becoming pro-cyclical because, unlike in other periods of global recessions or low growth, interest rates in big, advanced countries that primarily drive the SDRi have risen, not fallen. At the same time, Covid and the Russia-Ukraine war have led to a rapid increase in IMF lending (the pre-pandemic uptick in 2018-2019 was mainly because of a large loan to Argentina). Aggregate GRA credit outstanding has recently reached a record high.

As shown in Chart 2, this big rise in IMF lending alongside higher costs of borrowing is unprecedented since the inception of the Fund. Expansions of IMF lending have historically coincided with a falling SDRi, given that major central banks usually loosened monetary policy in response to global economic downturns that caused many countries to resort to the Fund. At least when looking at the aggregate, costs of IMF lending have typically moved in a counter-cyclical fashion: the IMF provided relatively cheap financing precisely when countries needed bailouts the most. Even in the early 80s, another period when many low and middle-income countries were faced with a debt crisis, the SDRi started to decline once IMF borrowing picked up sharply. Similarly, the large-scale IMF programmes after the 2008 global financial crisis were accompanied by a prolonged period of ultra-loose monetary policy and an SDRi at or close to its floor of only 0.05 per cent.

For the first time in history, we are now confronted with a rapidly rising SDRi while an unprecedented number of member countries need Fund support. And the situation may get even worse. Central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England (BoE), may stop hiking rates soon but may keep rates high for a long time or even hike further, if inflation continues to overshoot. Even the Bank of Japan may eventually have to let interest rates rise. This suggests the SDRi will remain high or may not yet have reached its peak. At the same time, the IMF recently estimated that demand for its loans is set to increase further. In its most adverse scenario for global growth, outstanding credit could even double to almost 200 billion in SDR (more than $260 bn) by the middle of next year.16 Whether that materialises depends in part on whether IMF lending can remain politically and economically attractive to debtor countries.

The increase in the SDRi is leading to more financing needs for existing IMF debtors, as well as making it harder for new debtors to borrow or even have a bailout programme. To give an example: the approval of the last IMF programme with Argentina took place at the beginning of 2022, coinciding with the start of the global monetary tightening cycle. The country was estimated to need to pay the Fund a basic rate of charge of around SDR 3.2 billion over the course of 2022-2032.17 But by the time of the programme review in March 2023, this amount had risen to more than SDR 10 billion.18 The programme with Argentina is an outlier given Argentina’s poor economic performance and it being by far the biggest programme in IMF history (in absolute terms). Argentina has been in dire economic straits for years, and the IMF, which needs to keep propping up Argentina to make sure it repays its loans, is locked in a financial marriage it cannot get out of. But the Argentina case does speak to a trend of larger programmes over the past decades, particularly after major financial crises.19 As can be seen in Chart 3, the growth of average programme size has coincided with a fall in the SDRi in the past. In the current situation, however, we see a strong increase in the SDRi at the same time as the average programme size is trending upwards. The tendency towards ever larger programmes shows no sign of abating. Recently, the IMF Executive Board temporarily increased the general access limits on the amounts that can be borrowed from Fund facilities, a decision taken in part to pave the way for extra IMF support to Ukraine.20

The bad implications of high IMF borrowing costs

High IMF borrowing costs can have several bad implications.

First, higher lending rates threaten to undermine the Fund’s ability to stabilise countries at a time of multiple shocks to the global economy.21 For debtor countries in economic distress, the burden of repaying high interest rates to the IMF itself takes away much-needed cash. This risks further exacerbating rather than alleviating their budgetary woes and hampers their prospects of economic recovery. Moreover, to protect the IMF’s financial resources and enable it to lend in future crises, the Fund has a de facto status as a preferred creditor: if a country defaults on its creditors, the IMF’s loans enjoy the highest level of protection and will be repaid above all the other creditors. The Fund’s senior status, coupled with the fact that it charges a rate of up to 8 per cent, could intensify inter-creditor disputes. To create space for the debtor country to repay the IMF, other creditors need to take even larger losses on their claims. That could reduce creditors’ willingness to engage in a debt restructuring or stoke conflict which makes it harder to come to an agreement. As a result, other creditors could even end up challenging the IMF’s preferred creditor status. But this status is a crucial, and non-negotiable, feature for the institutional design of the IMF, not only because it allows the Fund to retain its resources to fight future crises, but also because it allows members to treat IMF resources as powerful reserves on their central bank’s balance sheets.

Second, large and increasing payments to the Fund through higher lending costs could weaken the positive role of the IMF in mobilising private capital (the ‘catalytic effect’). Normally, extending IMF support, coupled with a programme of tough reforms, assures private investors that a country in turmoil is turning the page and thereby crowds in private money. Mounting debt repayments to the IMF, as the senior creditor, could instead crowd out private investors, who will have less faith that they will be repaid, and less hope of a strong economic recovery.22 This dynamic could also render the IMF’s large-scale precautionary lending facilities, such as the Flexible Credit Line (FCL), ineffective. The availability of such credit lines is an insurance mechanism: their mere presence stabilises countries without necessarily having to tap them. But, if another unexpected economic shock comes along, member countries might be forced to actually draw on the facilities, which at such high rates could become counterproductive.

Third, higher SDRi charges are leading to a growing redistribution of resources between rich creditor countries like the US and EU countries and debtor countries. SDR interest rate charges and their redistribution at current levels will reach SDR 3 billion by the end of 2023, a record level last observed in the mid-1980s. If the IMF’s worst-case scenario of deteriorating global economic and financial conditions materialises, demand for IMF resources will surge even more. The Fund estimates the credit under its GRA would then balloon to SDR 200 billion (around $263 billion). If the SDRi were to rise to an average of 5 per cent, the Fund would redistribute about SDR 10 billion per year from debtors to its richest member countries. The IMF’s lending is therefore not only becoming pro-cyclical, but also increasingly regressive.

If the IMF’s worst-case scenario of deteriorating global economic conditions materialises, demand for IMF support will surge even more.

Fourth, high Fund borrowing costs could also lead countries to seek alternative sources of financing, outside the scope of global governance, such as from bilateral (non-Paris club) creditors like China. Lending terms associated with these loans have often turned out to be opaque. There is evidence, for example, that China’s bilateral loans, as well as its subsequent bailouts, have often been driven by the pursuit of natural resources or diplomatic concessions.23 Moreover, they often require the borrowing countries to pledge ‘collateral’ to creditors: putting up certain assets as insurance against a default. An eye-catching example of this was the fact that Sri Lanka had to sign over Hambantota port over to Beijing on a 99-year lease because the country could not repay the Chinese loans it took out to build the port.24

Fifth, a high and rising SDRi also has repercussions for the Fund’s concessional lending activities to the poorest countries of the world. The Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) – the Fund’s main vehicle for providing cheap, concessional loans to low-income countries (LICs) – is currently lending at a subsidised rate of zero per cent. A higher SDRi (the rate at which the Trust Fund’s creditors get remunerated) increases the needed funds to subsidise these much cheaper zero per cent loans (the ’PRGT Subsidy Account’) and puts further pressure on PRGT finances, which are already under strain owing to substantially stronger demand for PRGT loans.25

Similarly, the rapid increase in the SDRi has also implications for the newly established Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST), which was created to help countries tackle the challenges of climate change. Countries can access the RST at a rate which equals the SDRi plus a modest margin (which varies according to the country’s income level). The strong increase in the SDRi has recently led the IMF Executive Board to adopt an interest rate cap of 2.25 per cent for the lowest income RST-eligible members to ensure they benefit from affordable lending terms. This, however, also slows down the pace at which adequate RST reserves are built because the IMF’s own income goes down. These reserves in turn are crucial to insure SDR contributions from creditor countries to the RST against any potential losses. That insurance in turn enables creditors to continue to treat their SDR contributions as foreign reserves on their central bank’s balance sheets, a status they can only retain if they are very unlikely to lose their value. This is a major prerequisite for rich creditor countries to rechannel some of the SDR’s they received in 2021 (as part of a general allocation of SDRs to all countries) to the RST in the first place.

Sixth, the IMF can also allocate new SDRs to member-countries, but the SDRi also sets the rate at which countries are charged if they actually use their SDR allocation. In August 2021, the IMF issued a general allocation of SDRs equivalent to about $650 billion. The allocation was meant to help members address the long-term global need for foreign reserves, and to build confidence in the face of the Covid pandemic raging at the time, thereby strengthening the global economy. It was also meant to help the most vulnerable countries struggling to cope with the impact of the Covid crisis.26 Many poor countries decided to draw on their new SDR allocation given their urgent financing needs during the pandemic. While countries do not have to replenish their holdings, they must pay the SDRi on the amount drawn. Drawing on the SDR allocation is thus akin to a perpetual loan with a variable interest rate – the SDRi. The latter was at its floor of 0.05 per cent when the SDRs were allocated in the time of Covid. However, as of now this – seemingly cheap – loan has turned into expensive credit especially for those countries who made active use of the 2021 allocation.27

An SDR interest rate ceiling would provide relief to debtor countries

The IMF should consider introducing a temporary cap on the SDR interest rate. A cap would prevent the Fund’s lending activities from becoming too expensive for its member countries at a time of multiple shocks to the global economy. It would help to reduce the potential for conflicts with other creditors, giving necessary debt write-downs more of a chance of to succeed. A cap would also ensure that private investors are not scared off by an overly large IMF interest rate burden for countries trying to resolve a crisis. Meanwhile, an SDRi ceiling would diminish the regressive redistribution of resources from poorer debtor countries to richer creditor countries. Finally, reducing IMF lending costs would discourage countries from seeking alternative more politicised sources of funding from bilateral creditors like China.

There is a precedent for setting limits to the SDRi: in 2014, the IMF introduced a floor to prevent the SDRi from turning negative during a period when central banks were pushing interest rates down aggressively. At the time, the IMF Executive Board amended the Rule T-1 to introduce a floor of 0.05 per cent.28 This was meant to prevent the SDRi from hitting zero or even becoming negative.29 Such an amendment of the Rule T-1 requires 70 per cent of the total voting power of the IMF shareholders, as laid out in Article XX Section 3 of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement.

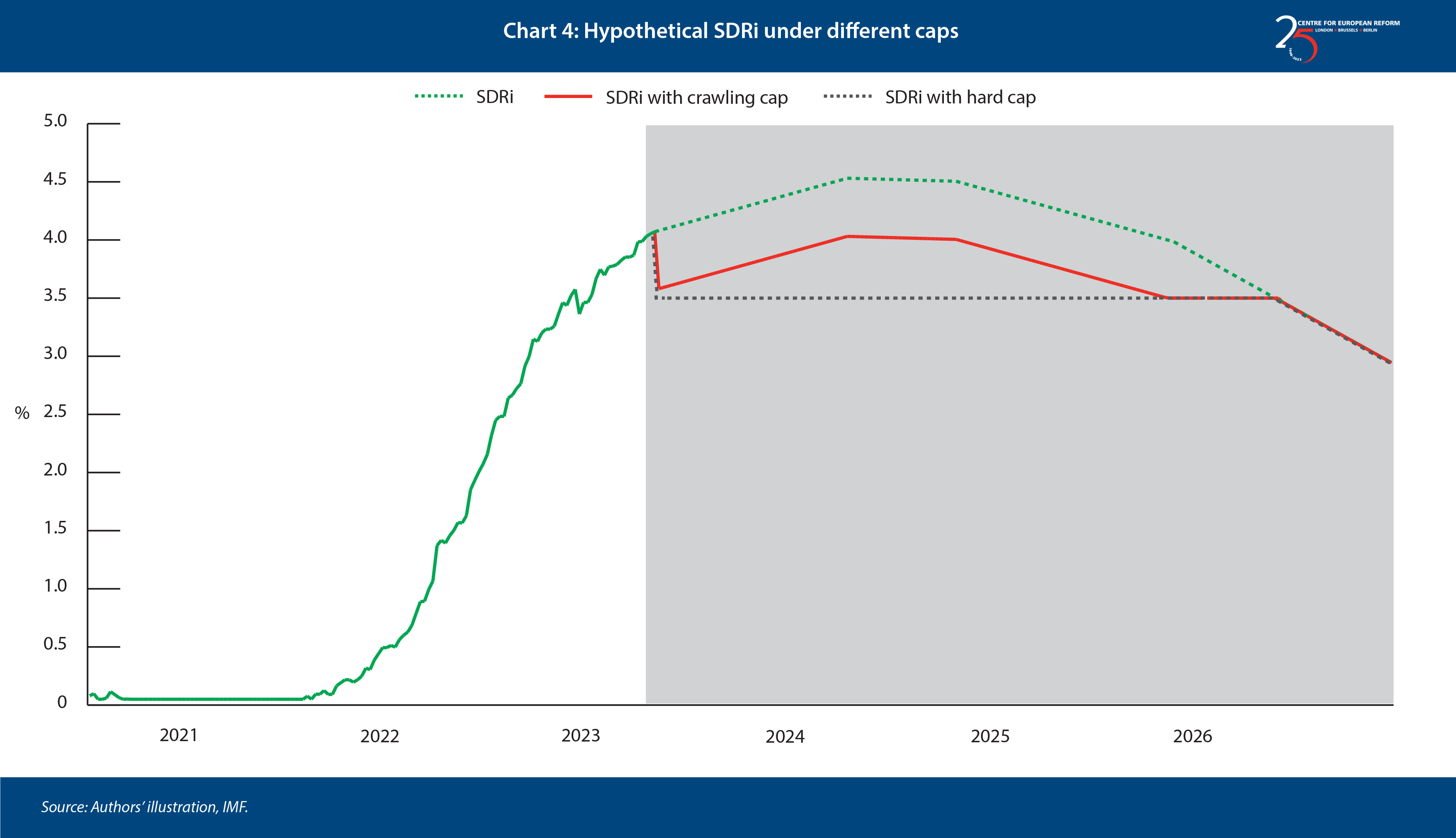

A cap on the SDRi could be designed in different ways. One option would be to simply introduce a hard cap at a level which is deemed appropriate, but on a temporary basis. The hard cap could expire automatically once global conditions change and the SDRi falls back below a pre-defined threshold. This would ensure that potential foregone revenues for creditor countries remain limited to the period in which strong global demand for Fund resources coincides with an environment of a global monetary tightening.

An alternative way to limit the rise in the SDRi would be an asymmetric ‘crawling cap’, that moves along with market interest rates. For instance, IMF could define a fixed reduction of the SDRi of, say, 0.5-1 per cent. This reduction would be fixed as long as the SDRi remains at its current level or keeps rising. Once the SDRi starts to fall, the fixed margin could be set to automatically decline and eventually disappear once the SDRi reaches a pre-defined level. This would effectively smooth the level and any further rise in the SDRi. As opposed to a hard cap, where a further rise in the SDRi would increase the size of foregone revenues, a crawling cap would keep the proportion of foregone revenues for creditor countries constant. Chart 4 illustrates these alternative cap designs for a hypothetical scenario of an SDRi that rises until the end of next year, before falling back to levels below 3.5 per cent thereafter (green dashed line).

Any of these caps on the SDRi would not affect the IMF’s income model. It would merely represent a lower (and less regressive) debtor-creditor redistribution inside the Fund’s General Resources Account and its SDR department. Depending on the chosen threshold, capping the SDRi would also provide substantial relief to the IMF’s largest debtors (Argentina, Egypt, Ukraine, Pakistan, and Ecuador). In fact, an SDRi cap at 2 per cent would lead to a bigger relief to these countries than eliminating the level-based surcharges, as these are only paid on the portion of credit above 187.5 per cent of a member’s quota. And it would not hurt the Fund’s ability to further accumulate precautionary balances which serve as a buffer against potential losses, which is crucial at a time when the Fund should be taking more risk to protect the global economy.

Possible concerns about an SDR interest rate ceiling

There are several possible arguments against an SDRi cap.

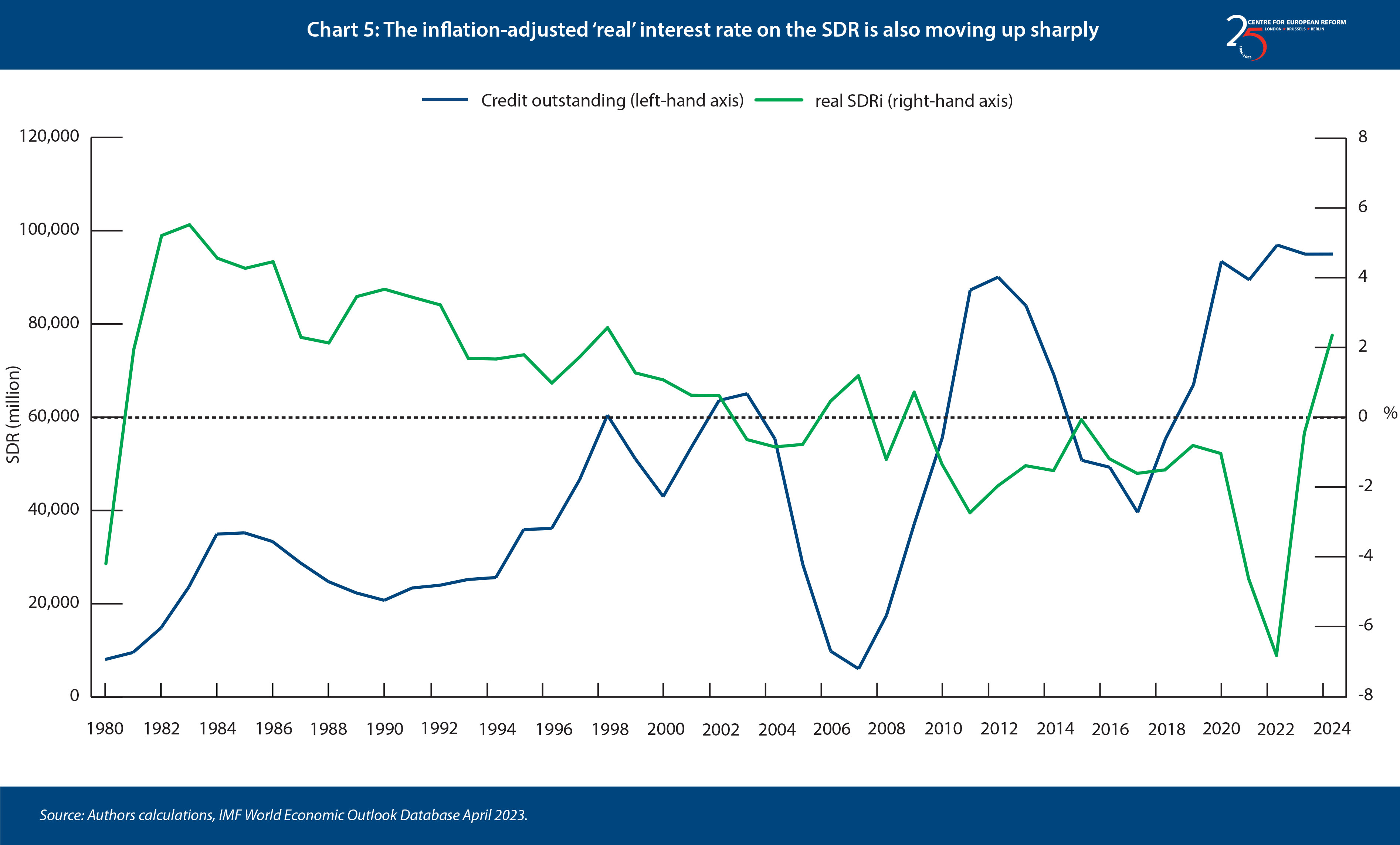

One objection might be that it is only the real interest rate, stripped out from inflation, that matters. Inflation levels are high in many emerging markets, reducing the effective real cost of borrowing from the Fund. That suggests a rising nominal SDRi is less of a problem. However, it is not just the nominal interest rate and domestic inflation rate that matter for countries’ debt sustainability. The exchange rate and the ability to generate enough export revenues to service a country’s obligations in foreign currency are just as vital. All else equal, a rising SDRi increases payments due in foreign currency. At the same time, higher domestic inflation, and monetary tightening of major central banks tends to put pressure on the (real) exchange rate of many emerging and developing economies, worsening their debt dynamics. A high and rising SDRi results in higher payments to the Fund and adds to this drag. Besides, even in real terms, the SDR’s interest rate is rising fast, as outlined in Chart 5. That trend may well continue as inflation pressures globally come down and increasingly fall below the nominal interest rates set by central banks, thus leaving a higher real (post-inflation) interest rate.

Second, some may be concerned that the introduction of an SDRi-cap could constitute monetary financing of governments. But the resulting lower remuneration of the IMF’s creditor members from a cap does not constitute a direct transfer of money from any central bank to the government. It should be seen, rather, as foregone SDR revenues for the central banks of creditor countries. The creditor governments would forsake interest to support debtor governments, in the same way that they let go of some interest rate income when the SDRi floor was introduced. A negative SDRi would also potentially have led to increased central bank revenues, for instance, by charging a negative rate on those funds that the IMF holds in its own accounts at members’ central bank for administrative expenditures and receipts (so-called No. 2 Accounts). But, in the context of the discussion on introducing the floor, the IMF and its members did not end up siding with such concerns.

Lower remuneration from a cap should be seen as foregone SDR revenues for the central banks of creditor countries.

A third possible concern is that an SDR cap constitutes active interference with a market-determined price. Such concerns certainly did not stop the IMF from introducing an SDRi floor. But, more importantly, the SDRi cannot be equated with a price purely determined on the market. While the SDRi is based on combined market interest rates of the basket of five reserve currencies, the respective composition of the currencies as well as their respective weights are, essentially, set by the IMF based on an invented rule (specified in rule “Rule O-1”). For instance, under a different criterion that would increase the weight of the Japanese yen, the SDRi would drop significantly.

Fourth, some may fret that an SDRi cap would require an overhaul of all loan agreements between the IMF and its creditors both in the GRA and PRGT/RST. Thankfully, the bilateral loan agreements between the IMF and creditor countries as well as the New Arrangements to Borrow (NAB) – a backstop agreement between the IMF and a group of members and institutions – only refer to “the rate at which it pays interest on holdings of Special Drawing Rights”. This rate is specified in Rule T-1. Hence, changing only the way at which the SDR rate is calculated should not trigger any immediate repercussions for the IMF’s various loan agreements. The same is likely to hold true for member’s bilateral contributions to the PRGT and RST.

A fifth possible concern is that an SDR cap could lead to big losses for major creditors, including Europe’s central banks. For European central banks the main benchmark for the costs of their liabilities should be the ECB’s deposit rate. But given that the dollar has by far the highest weight in the SDR basket and interest rates are higher than in Europe, the SDRi is higher than the ECB’s deposit rate. Hence, there would still be some room to ‘lower’ the SDRi without European central bank balance sheets incurring any ‘losses’. A similar but slightly different argument holds also for the US. The US is one of the few countries where it is not the central bank but rather the US Treasury which provides the paid-in capital for the IMF. As such, revenues on creditor positions inside the IMF should be compared to the Treasury’s long-term refinancing costs. Given the highly inverted yield curve in the US, in which interest rates on long-term bonds are lower than those with short maturities, there is still room for a lower SDRi before the Treasury would incur any ’losses’.

Sixth, an SDRi cap may set a precedent and could lead some to worry that it may become permanent. But the current situation is unique in the history of the Fund so far. After having just coped with a pandemic, the global economy was hit by a major inflationary shock caused by Russia’s war on Ukraine. Hence, major central banks were forced to rapidly tighten monetary policy in a situation of relatively low growth, elevated debt levels, and at a time when the IMF has substantially increased its financial exposure to its membership to help it deal with a global pandemic. These unique circumstances should provide sufficient reason for member countries to make any SDRi cap temporary. Moreover, the respective amendment to rule T-1 could easily be formulated in a way that the cap is removed once the SDRi has fallen below a pre-defined threshold. Any subsequent decision on the reintroduction of an SDRi cap would once again require a 70 per cent voting majority and therefore need to be appropriately justified.

A final counterargument is that a higher SDRi is not a problem if it remains cheaper than market financing rates. Financing terms should not be entirely de-linked from alternative funding on the market. But countries approaching the Fund are typically in distress and often have lost access to private capital markets or are struggling to refinance all their external gross financing needs at terms compatible with long-term debt sustainability. As such, the IMF as the world’s lender of last resort should not provide financing at terms that worsen a country’s debt dynamics. Besides, the Fund is a super-senior creditor that only lends subject to certain conditions. These two features are the reason why the IMF provides financing at favourable rates at all. To provide a simple example: imagine if a eurozone country was struggling to refinance its government debt because interest rates for their government bonds had risen to about 8 per cent. If the IMF or the eurozone bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism, stepped in and provided large (super-senior) loans of, say 7, per cent, the loans would technically be cheaper than market financing, but the intervention would undoubtedly fail to stabilise the situation.

Conclusion

The IMF is the multilateral port of call for countries in debt distress to seek bailouts and get back on their feet. During the past fifty years, the IMF has extended most of its financial assistance in periods when interest rates were low or declining from previous levels, so its lending activities and associated costs have – at the aggregate level – historically been countercyclical. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, however, the IMF has been increasing its overall financial assistance to its membership while its lending costs are rising. This makes it harder for countries to turn to the IMF even though global economic growth is weak, bond market finance for emerging and developing countries has frozen up, and middle- and low-income countries potentially face their largest debt crisis since the 1980s. The IMF’s role is also subject to other pressures: China has become a major global creditor but has refused to join the Paris Club, and it is seeking to provide an alternative to the Fund.

The US and the EU remain by far the IMF’s largest shareholders: if they want to minimise the risks of the IMF becoming less relevant or effective, they should act to reduce its high lending rates during this stagflation episode.

The IMF should therefore introduce a temporary ceiling on its SDRi. Such a ceiling comes with many advantages. First, it would keep the Fund’s bail-out programmes more accessible and effective for its member countries at a time of multiple shocks to the global economy. Second, a temporary cap on the IMF SDRi would reduce a regressive redistribution of resources from poorer debtor countries to richer creditor countries. Third, reducing IMF lending costs would discourage countries from seeking out alternative funding from bilateral creditors outside the scope of global governance. Fourth, capping the SDRi would reduce the need to further subsidise resources to the IMF’s Trusts for low-cost financing for the poorest countries.

The EU is fretting about fraying multilateral institutions undermining global rules. The US wants to counter Chinese competition for global influence. And the transatlantic pair have expressed indignation about the lack of condemnation of Russia from dozens of developing countries. If they want to turn the tide, they should seriously consider ways to make IMF lending available and affordable for emerging market and developing countries in their time of need.

2: Theo Maret, ‘Sovereign restructurings: A logjam long in the making’, Substack, March 8th 2023.

3: Brad Setser, ‘The Common Framework and its discontents’, Council on Foreign Relations, March 26th 2023.

4: Sebastian Horn, Bradley Parks, Carmen Reinhart and Christoph Trebesch, ‘China as an international lender of last resort’, Kiel Working Paper, March 2023.

5: James Undquist, ‘Bailouts from Beijing: How China functions as an alternative to the IMF’, Boston University Global Development Policy Center, working paper, February 2021.

6: IMF, ‘IMF executive board approves extension of increased access limits under the Rapid Credit Facility and Rapid Financing Instrument’, press release, October 5th 2020; and IMF, ‘The Rapid Credit Facility (RCF)’, fact sheet, September 2023.

7: This is owed to the IMF’s General Resource Account.

8: IMF, ‘Special drawing rights’, factsheet, January 2023.

9: IMF, ‘IMF lending’, factsheet, July 2023.

10: IMF, ‘Surcharges: Frequently asked questions’, accessed on September 26th 2023.

11: IMF’, ‘Review of the Fund’s income position for FY2023 and FY2024’, June 2023.

12: IMF, ‘IMF lending’, factsheet, July 2023.

13: Joseph Stiglitz and Kevin Gallagher, ‘IMF surcharges: A lose-lose policy for global recovery’, CEPR, February 2022.

14: Andrea Shalal, ‘IMF shareholders deeply divided on whether to suspend surcharges on some loans’, Reuters, December 12th 2022.

15: IMF, ‘Review of the adequacy of the Fund’s precautionary balances’, December 2022.

16: IMF, ‘Review of the adequacy of the Fund’s precautionary balances’, December 2022.

17: IMF, ‘Argentina: Staff report for 2022 Article IV consultation and request for an extended arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility’, press release; staff report; and staff supplements, March 2022.

18: IMF, ‘Argentina: Fourth review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility, requests for modification of performance criteria, waiver of nonobservance of performance criteria, and Financing Assurances Review’, press release; staff report; and statement by the Executive Director for Argentina, April 2023.

19: Tobias Krahnke, ‘Doing more with less: How the IMF should respond to an emerging market crisis’, CEPR, April 202.

20: IMF, ‘Temporary modifications to the Fund’s annual and cumulative access limits’, policy paper, March 2023.

21: Anne Krueger, ‘The great debt conundrum’, Project Syndicate, September 19th 2023.

22: Tobias Krahnke, ‘Doing more with less: The catalytic function of IMF lending and the role of program size’, Journal of International Money and Finance, volume 135, 2023.

23: Keith Bradsher, ‘After doling out huge loans China is now bailing out countries’, New York Times, March 27th 2023.

24: Jonathan Hillman, ‘Game of loans: How China bought Hambantota’, Center for Strategic & International Studies’, April 2nd 2018.

25: IMF, ‘2023 review of resource adequacy of the poverty reduction and growth trust, resilience and sustainability trust and debt relief trusts’, press release, April 7th 2023.

26: IMF, ‘2021 General SDR allocation’, August 2021.

27: Neil Shenai, Nicolas End, Jakree Koosakul and Ayah Said, ‘The financial costs of using special drawing rights: Implications of higher interest rates’, IMF working paper 2023/193, 2023.

28: IMF, ‘IMF executive board modifies rule for setting SDR interest rate’, press release, October 24th 2014.

29: IMF, ‘Financial operations 2018’, April 2018.

Tobias Krahnke and Sander Tordoir, senior economist at the Centre for European Reform

September 2023

View press release

Download full publication