Turkey and the UK: New best friends?

Turkey and the UK want to maintain a close relationship after the Brexit transition ends. But concluding a trade deal will not be easy, and relations could sour if tensions increase between Turkey and the EU or US.

A UK-Turkey trade deal is “very close”, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said on a visit to the UK in early July. The importance placed on securing a post-Brexit trade deal reflects the significance of the commercial relationship, particularly to Turkey. In 2018, Turkey exported £10.6 billion of goods and services to the UK, its second most important export market after Germany. But when the UK exits the Brexit transition period at the end of the year, it will also leave the EU’s customs union with Turkey, meaning that the UK-Turkey trading relationship will fundamentally change.

A UK-Turkey trade deal is important for both countries commercially and politically. Bilateral relations have strengthened in recent years just as both countries’ relationships with the EU have deteriorated. Brussels and Ankara have clashed over the erosion of democratic checks and balances in Turkey as well as Turkey’s increasingly assertive foreign policy in Libya and the eastern Mediterranean, especially its drilling off the coast of Cyprus. Tensions have meant that the EU has been unwilling to launch negotiations to modernise the EU-Turkey trade relationship and extend liberalisation to areas such as services and procurement. Meanwhile, Turkey’s relationship with the US has also become increasingly tense, particularly after Ankara purchased a Russian missile system despite US and NATO opposition. The UK is one of Turkey’s few remaining friends in the West, and for Ankara a trade deal would signal a close economic and political relationship with a major European power. For its part, the UK has been keen to cultivate a good relationship with Ankara as part of its ‘Global Britain’ quest for post-Brexit trade deals and political partnerships.

The UK is one of Turkey’s few remaining friends in the West.

When it was still an EU member, the UK was one of the leading advocates of Turkish membership of the EU. The UK was quick to condemn the attempted coup in Turkey in 2016, winning plaudits in Ankara. In early 2017, the UK and Turkey concluded a deal that would see BAE Systems take part in a project to build a fighter jet for Turkey’s airforce. London has also been much less vocal than other European capitals about the domestic situation in Turkey, and has largely avoided criticising President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his government. When Turkey launched a military operation in Syria in October 2019, the UK was initially reluctant to condemn Ankara, unlike other NATO allies. The UK has been less critical than some European countries of Turkey’s intervention in favour of the UN-backed government in Libya. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity for the two countries to work together: Turkey sent protective equipment to the UK, with its government stepping in to help after an order the UK had placed with a private company fell through. And, unlike the EU, the UK has exempted Turkey from quarantine measures, offering a lifeline to the Turkish tourism industry.

But a trade deal is not a straightforward matter. Turkey’s economic relationship with the UK is dependent on the future EU-UK deal. The UK’s exit from the EU customs union makes it inevitable that UK-Turkey trade will change significantly. Turkey is in a partial customs union with the EU, covering industrial goods and some processed food (trade in agriculture is covered by a separate agreement that the UK and Turkey will also need to replicate). Goods covered by the customs union arrangement can be sold tariff and quota free into the EU, with no need for exporters to worry about costly rules of origin procedures. This is because Turkey is required to apply the same (or at least not lower) tariffs as the EU to goods imported from elsewhere. Turkey is also required to mirror the EU’s trade policy, negotiating free trade agreements with the same countries and matching the EU’s tariff reductions and rules of origin criteria.

Turkey’s customs union with the EU ties Ankara’s hands when it comes to negotiating a new deal with the UK. While Turkey is able to negotiate its own trade agreements, and has a free hand in areas not covered by its customs union with the EU, such as services and agriculture, when it comes to removing tariffs on industrial goods (Turkey’s most significant export sector), the Turkey-UK relationship must match the EU-UK relationship. This means that if the EU and UK fail to reach an agreement before the end of the year, there will be tariffs on goods going from the UK to Turkey, and in theory also between Turkey and the UK.

Some policy-makers in Ankara might be tempted to breach the terms of Turkey’s customs union with the EU, and strike a trade deal with the UK even if even if there is no UK-EU agreement. This has happened before with Malaysia, much to the EU’s chagrin, where the EU failed to conclude its trade negotiations, but Turkey went ahead and signed a deal anyway. A UK-Turkey agreement, under such circumstances, would potentially cause the EU-Turkey customs union to break down entirely due to the significant risk of large volumes of British goods and inputs being transhipped into the EU via Turkey. Such a deal would lead to yet more friction between Ankara and Brussels, and strengthen the voice of those who advocate a tougher EU stance towards Turkey, including more sanctions and an end to accession negotiations. The UK should think carefully before pursuing a trade agreement that would further destabilise the EU’s relationship with Turkey, and run the risk of being viewed as a deliberate provocation by Brussels.

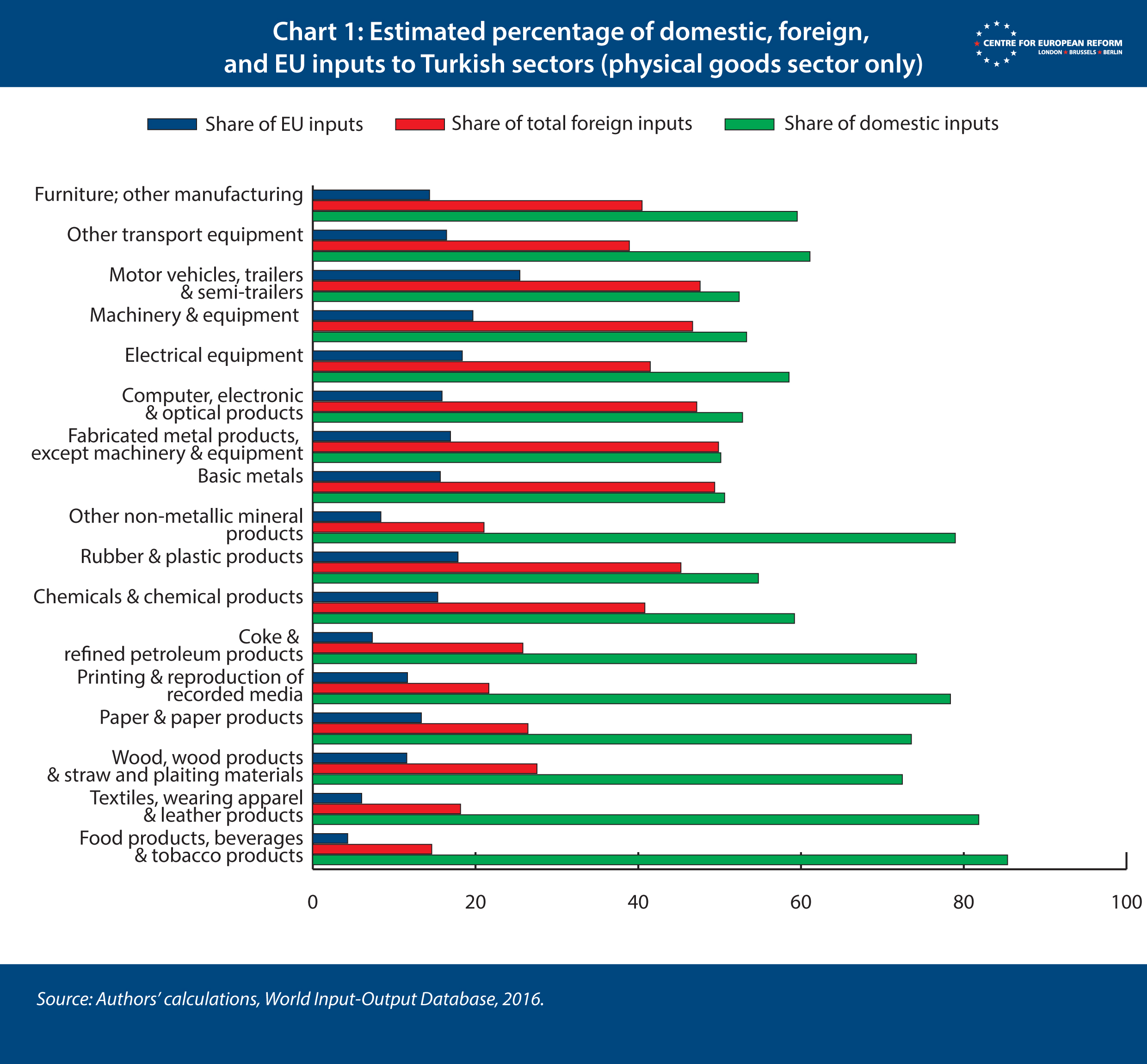

However, even if the EU and UK, and therefore Turkey and the UK, do conclude a free trade agreement that removes tariffs and quotas on industrial goods, this would still represent a steep deterioration in the terms of trade relative to the existing arrangements, and cause problems for companies trading between the UK and Turkey. Unlike trading within a customs union, in order for an exported good to qualify for tariff free trade under a free trade agreement, it needs to meet specific rules of origin criteria. This is to ensure that the export does not come from somewhere else. To give a specific example, EU trade agreements, and therefore Turkish trade agreements, often require at least 60 per cent of the value of an exported car to have been created locally for it to qualify for zero tariffs. If a similar threshold were to apply to a trade agreement with the UK it would create an issue for some Turkish car exporters, as they only source around 50 per cent of their inputs within Turkey (Chart 1).

Even for sectors which source a large proportion of their inputs locally, rules of origin can create difficulties. For example, EU free trade agreements often include arduous rules of origin criteria in respect of exported textiles. For example, for a printed t-shirt made of imported cotton to qualify for zero tariffs it might also need to be subject to two further stages of manufacturing in Turkey such as scouring and shrink resistance processing. Failing that, the t-shirt would be subject to tariffs when entering the UK.

While the additional rules of origin compliance burden cannot be removed entirely, the UK and Turkey could theoretically take steps to make it easier for exports to qualify for a future free trade agreement. They could, for example, simplify rules of origin qualifying criteria and/or both agree to allow for EU-27-sourced inputs to count towards local value-added thresholds – so called ‘cumulation’. However, Turkey is bound by the terms of its customs union with the EU to replicate the rules of origin criteria applied in the EU-UK FTA in its own trade deal with Britain. This means that flexibility of the sort proposed above can only exist if the EU first agrees to it in its own negotiations with the UK.

The UK has asked for flexible rules of origin, and in particular for ambitious cumulation provisions, in its trade talks with the EU, but so far the EU has not been receptive. This could change as the negotiations continue over the summer, so the UK should keep pushing the issue. The UK should also consider joining the Pan-Euro-Mediterranean convention on rules of origin – this off-the-shelf treaty allows for cumulation and for inputs from all 20 signatories, including the EU and Turkey, to count towards local content thresholds in their respective FTAs with each other.

However, if the UK is prepared to forego reciprocal treatment for its own exports to Turkey, there is another option. Unlike Turkey, which is constrained by its customs union with the EU, the UK is also able to act unilaterally to mitigate problems for Turkish exporters. For example, assuming a UK-Turkey FTA is agreed, the UK could unilaterally decide to adopt a flexible approach to rules of origin and imports from Turkey. It could, for example, allow for imports from Turkey to enter duty free irrespective of their originating status for a temporary grace period. This would allow more time for Turkish companies to adapt their supply chains and ensure their exports comply with the FTA’s rules of origin requirements.

Ultimately, avoiding trade disruption with Turkey is just another reason the UK should prioritise reaching a trade agreement with the EU before the end of the year. But even if the UK and Turkey manage to secure a FTA, the future of their relationship will depend on broader political developments, particularly on the health of Turkey’s relationships with the EU and the US. For example, if the EU imposes additional sanctions on Turkey before the end of the transition period, the UK will also have to apply them under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement.

Even if the UK and Turkey manage to secure a FTA, the future of their relationship will depend on broader political developments.

More broadly, the more Turkey clashes with the EU, individual member-states, or the US over issues like Libya and the eastern Mediterranean, the more complicated it will be for the UK not to be drawn into the argument. As one of Turkey’s closest partners, the UK should resist the temptation to conclude a trade deal with Turkey without first having done so with the EU, as this would bring it limited benefits but would further poison EU-Turkey relations. At the same time, London should warn Ankara about the risks of pursuing a more assertive foreign policy, encourage it to engage in dialogue with its neighbours to resolve differences and try to de-escalate tensions.

Sam Lowe is a senior research fellow and Luigi Scazzieri is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment