A perfect storm: Britain's trade malaise, weak growth and a new geopolitical moment

The UK is facing its most severe trade challenge in decades – and at the worst possible time. If the Labour government is committed to fostering sustained growth, it must place trade at the heart of its economic plans.

Since taking office in July 2024, Britain’s Labour government has made economic recovery its central priority. Strikingly absent from its growth plans is a focus on trade. However, the UK is currently experiencing the most severe trade stagnation in a generation – and one that has undermined post-pandemic recovery and continues to weigh heavily on the country’s growth prospects. For the Labour government to revive stalled growth, trade must be placed at the heart of its economic strategy.

Since taking office in July 2024, Britain’s Labour government has made economic recovery its central priority. Strikingly absent from its growth plans is a focus on trade.

Britain’s trade malaise

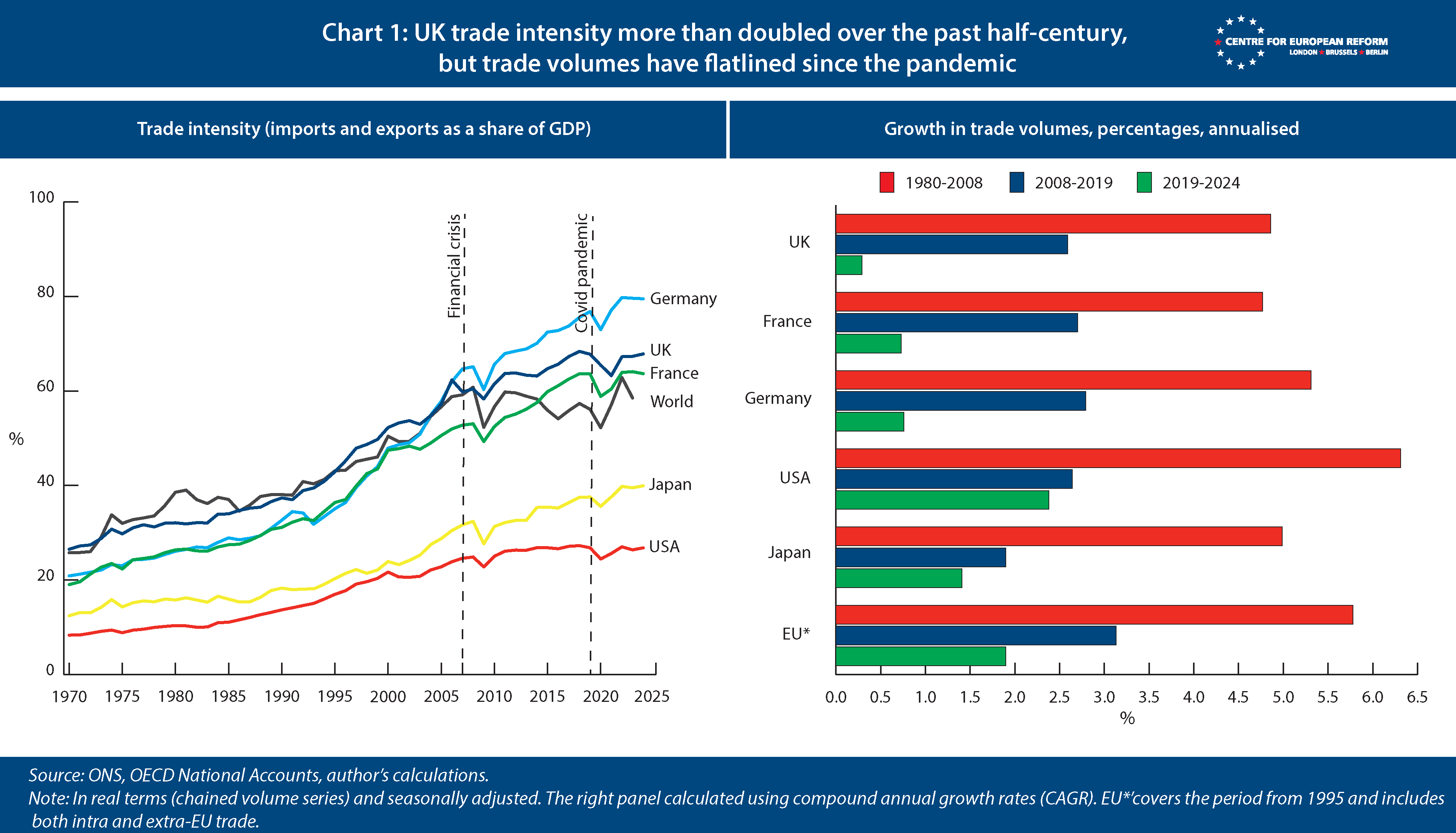

Over the past 50 years, the UK has steadily become more open to trade. The combined value of imports and exports as a share of GDP has more than doubled, from 30 per cent in 1975 to 67 per cent in 2024 (Chart 1, left panel). This transformation helped fuel several decades of rising living standards, as global trade liberalisation brought cheaper products to consumers and expanded opportunities for British businesses on the global stage.

Three distinct phases can be identified in the story of Britain’s trade openness (right panel). First came the great liberalisation that began in the 1980s and continued until the 2008 financial crisis, when trade volumes grew at nearly 5 per cent annually. The post-2008 era was marked by a slowdown in trade, with growth at above 2 per cent per annum. Since 2020, as Britain experienced the dual shock of the pandemic and Brexit, UK trade has not merely decelerated – it has flatlined in real terms, marking a sharp break from past decades. The UK’s trade performance largely mirrored global trends until 2020, after which trade volumes have suffered a particularly severe setback and, in contrast to many other countries, have not yet fully recovered.

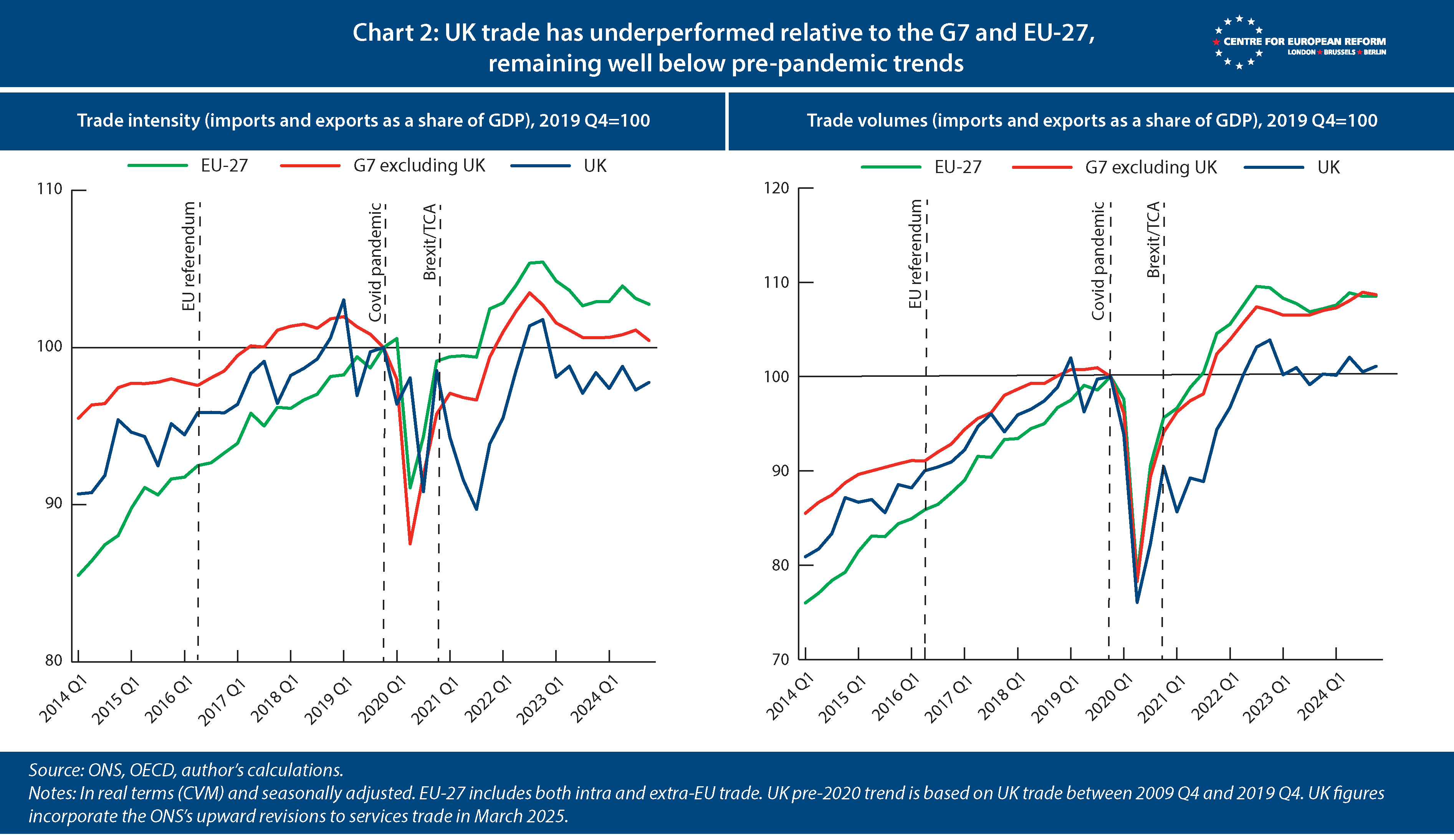

Today, the UK finds itself in an unenviable position. At the end of 2024, trade intensity remained 3.5 per cent below pre-pandemic levels, even as it rose by 1 per cent across the G7 and 3 per cent across the EU-27 (Chart 2, left panel). While nominal trade has grown, much of this growth was driven by elevated inflation. In real terms, UK trade volumes have grown just 1 per cent on their 2019 levels, compared to an 8 per cent growth in both the G7 and EU-27 (right panel). The gap between the UK’s performance and that of its peers is large and widening, pointing to a structural weakness in Britain’s trade position that cannot be ignored.

Britain’s trade and weak growth

There are two key reasons why Britain’s poor trade performance is significant: its impact on productivity growth and its role in GDP performance. The link with productivity is particularly important. Productivity growth – the ability to create more economic value with fewer resources – is ultimately what determines long-term living standards. Evidence shows that trade plays a critical role in driving productivity: it exposes domestic firms to international competition, spurs innovation, reduces costs, and spreads new technologies. When trade stagnates, these forces dissipate: firms face less competitive pressure, diffusion slows, and investment in productivity-enhancing activities declines. Over time, this results in sluggish productivity growth and reduced living standards.

There are two key reasons why Britain’s poor trade performance is significant: its impact on productivity growth and its role in GDP performance.

The relationship between trade openness and productivity growth has historically been strong in the UK. Increases in trade volumes tended to precede productivity gains. However, following the 2009 financial crisis, this link weakened. Despite a rebound in trade volumes, productivity growth remained stagnant. Since the pandemic, both trade and productivity have declined. While business underinvestment and slow innovation diffusion are major contributors to the UK’s long-term productivity woes, the UK’s current trade malaise appears to be compounding the problem.

Trade also affects short-term GDP growth, even though interpreting its role in GDP can often be misleading. Net exports are typically a volatile component of national accounts, and imports are often mistakenly viewed as a drag on economic output. In reality, imports are GDP-neutral and their growth often signals healthy domestic demand. A more useful metric is to examine the contribution of exports to GDP growth, as this more accurately indicates whether external demand is stalling or whether the competitiveness of exports is changing.

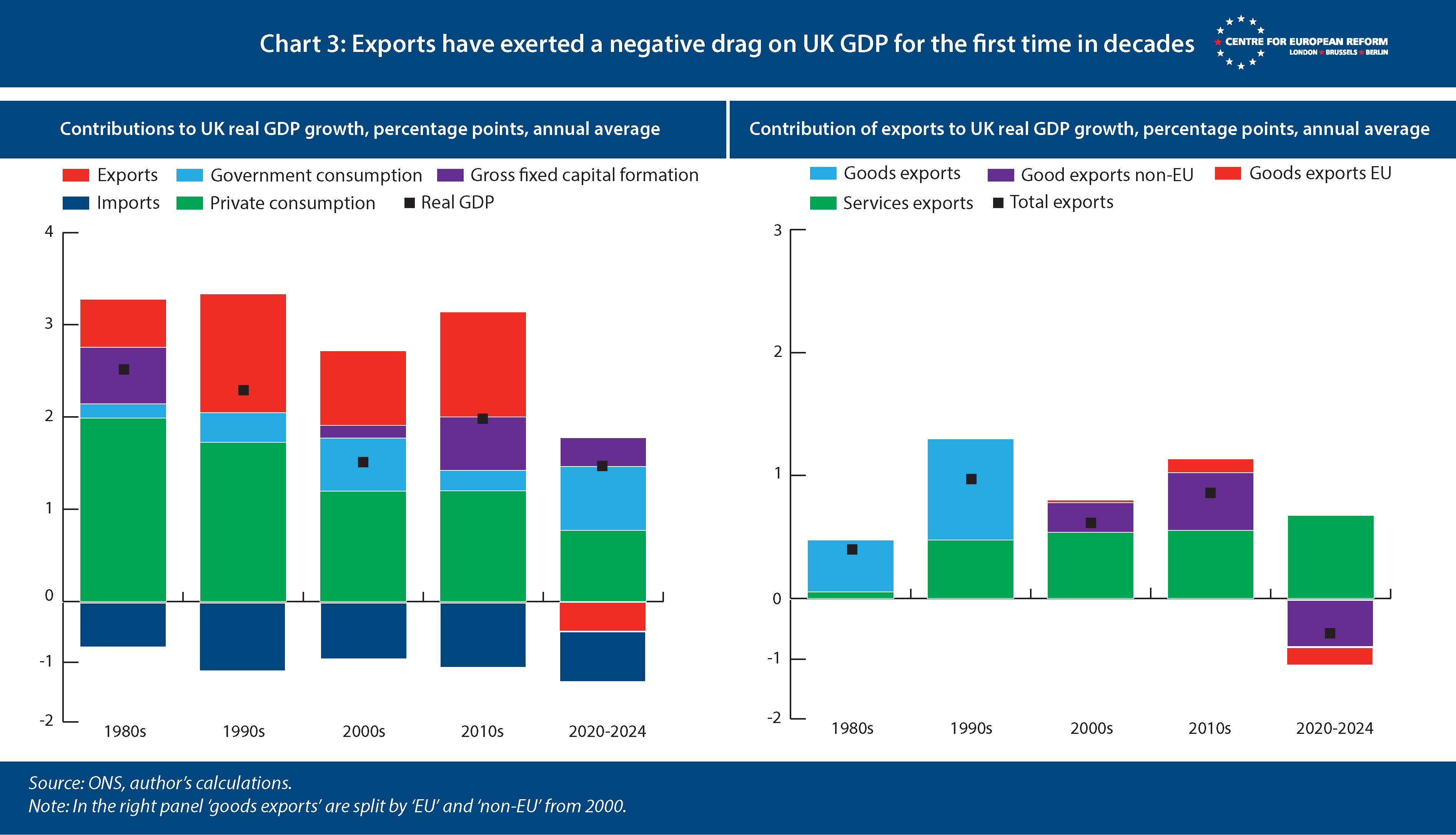

Exports have historically contributed positively to UK real GDP growth (Chart 3, left panel). Since 2020, however, exports have become a drag on UK GDP growth, on average subtracting nearly 0.5 percentage points per annum. The fall in goods exports, in particular, has had a significant impact, reducing GDP growth by more than 1 percentage point annually (right panel). This decline has been driven by the drop in both EU and non-EU goods exports, with non-EU exports having twice as large an impact. In contrast, services exports have continued to grow and contribute positively, though not enough to offset the broader decline in goods exports.

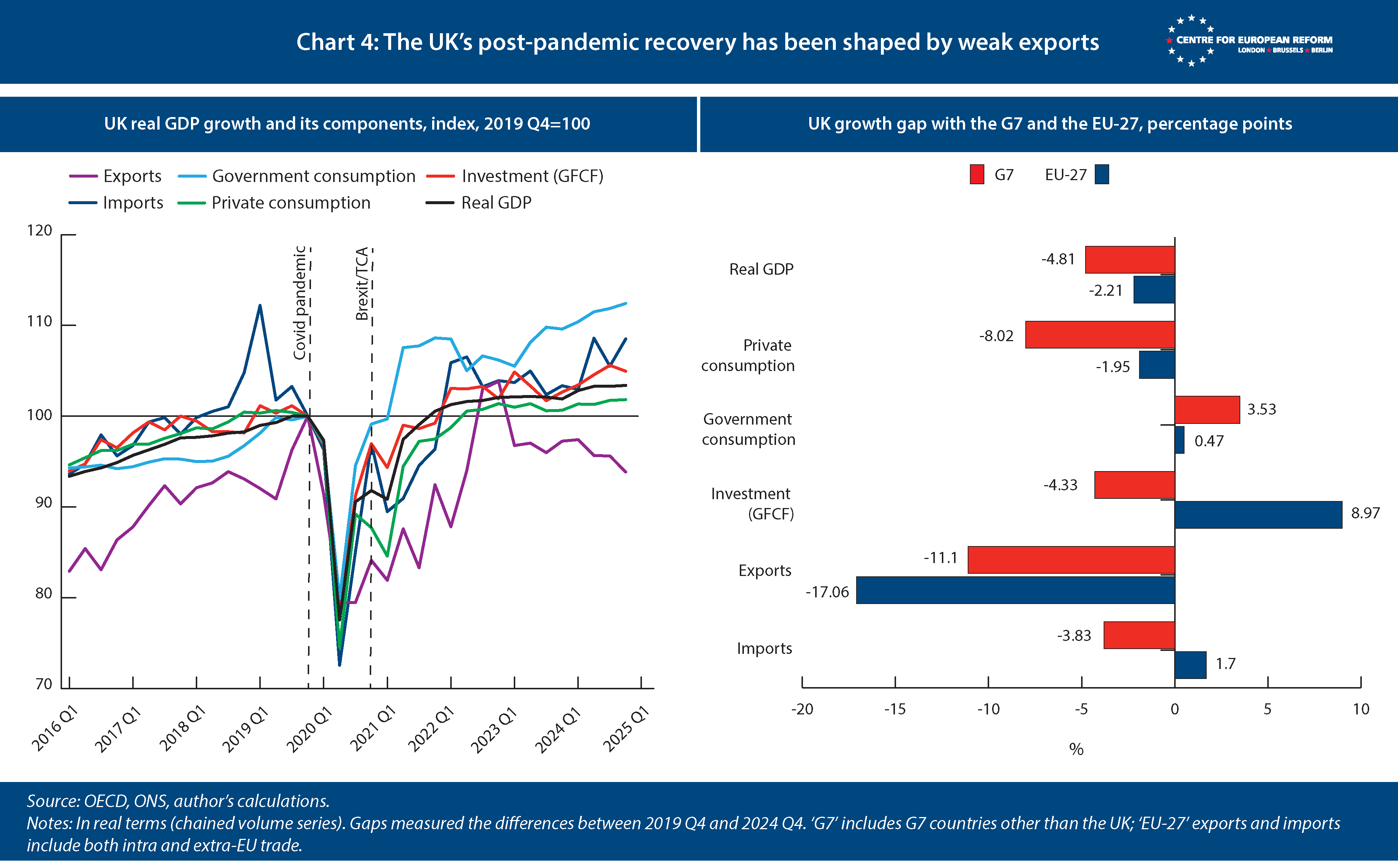

The collapse in goods exports has had a significant impact on the UK’s post-pandemic economic recovery. Consumption, government spending, and investment have all surpassed pre-pandemic levels, except for exports, which remain below their 2019 levels (Chart 4, left panel). The decline in exports is also largely responsible for the UK’s underperformance relative to its peers (right panel). Compared to the G7 average, UK real GDP is nearly 5 percentage points lower than pre-pandemic, with exports lagging 11 percentage points behind. Against the EU-27 average, the overall GDP gap was narrower – around 2 percentage points – but the exports gap is wider still, at an astonishing 17 percentage points average. The UK stands out as a real outlier when it comes to post-pandemic trade.

A tale of two trades

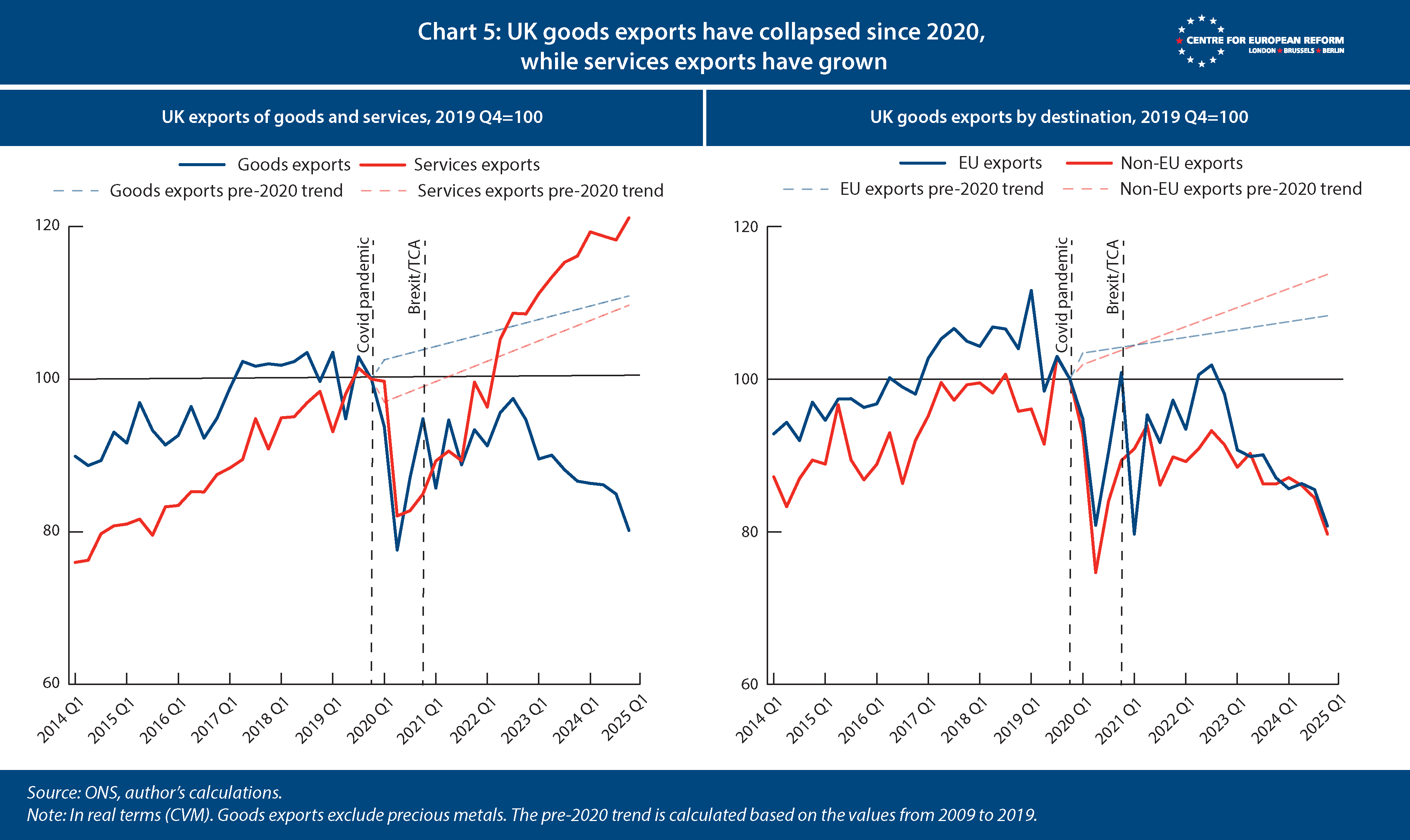

The most striking feature of the UK’s recent trade performance is the extraordinary collapse in goods exports while services exports have boomed.

By the end of 2024, goods exports were 20 per cent below their 2019 levels (Chart 5, left panel). Had they kept pace with the pre-pandemic trend, goods exports would have been 30 percentage points higher. In contrast, services exports have grown robustly by 21 per cent since 2020, but not enough to offset the losses in goods exports. As a result, the share of services exports in the UK economy is now at its highest level on record, while goods exports have reached their lowest share of GDP since 1993. This shift in the composition of British exports has important implications for the UK’s industrial strategy, which should place export-oriented services sectors at its centre.

The more puzzling question is why, considering Brexit, goods exports have fallen to both EU and non-EU exports in tandem (Chart 5, right panel). One possible answer is that significant new frictions in trade with the EU are affecting supply chains across the board. As intermediate inputs sourced from European markets became costlier, the relative price of UK exports rose, and competitiveness declined across the board. This is also why many British manufacturers have, in recent years, reoriented towards the domestic market at the expense of exporting overseas: manufacturing output has declined by 4 per cent since 2020, while manufacturing exports are 15 per cent down.

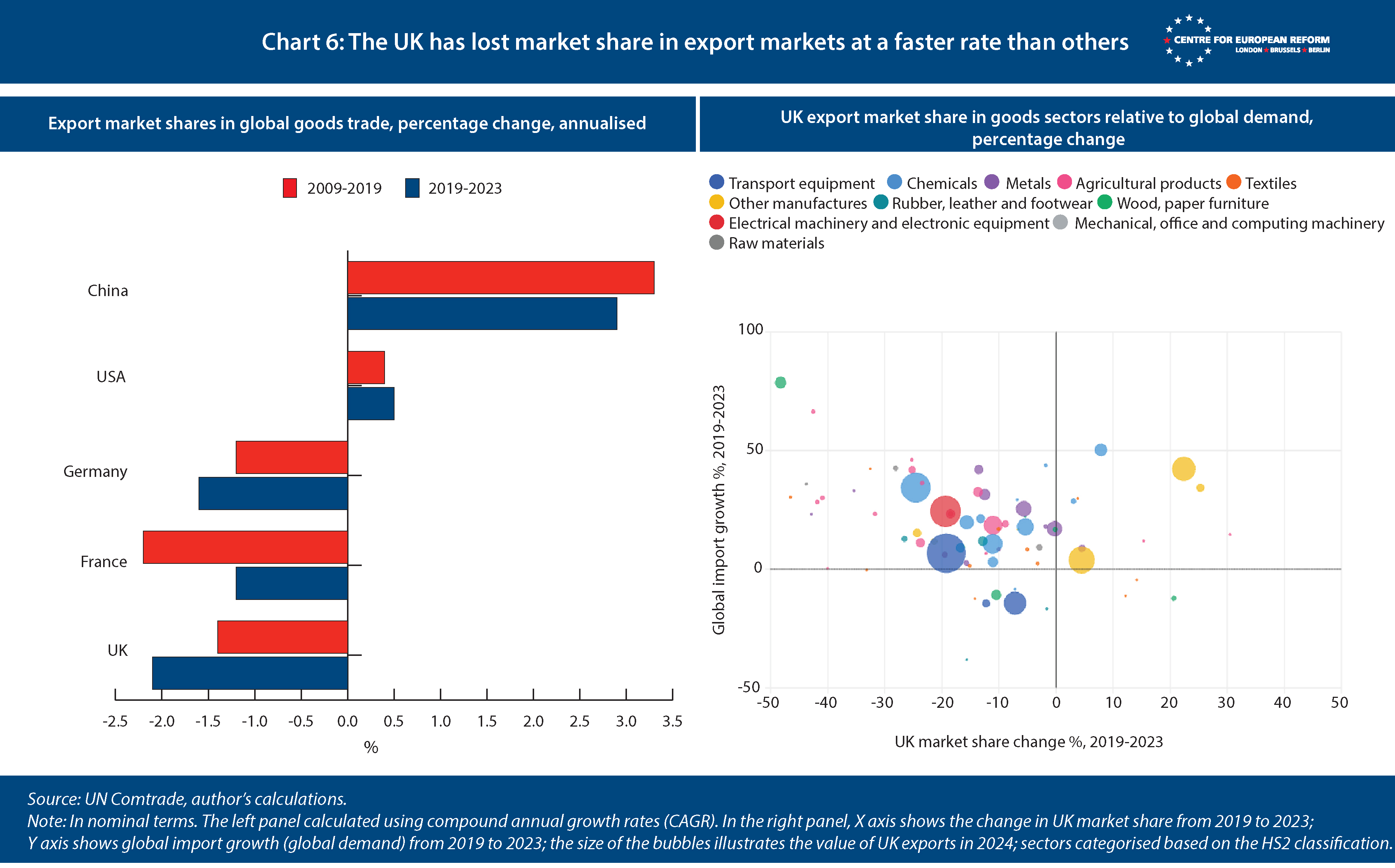

The broader story is one of a loss of competitiveness. This is not an entirely new development; the UK has steadily lost market share in global export markets in recent decades. Between 2009 and 2019, UK market share fell by about 1.5 per cent annually (Chart 6, left panel). However, the fall in UK export market share has accelerated since the pandemic and Brexit, surpassing even the losses experienced by a major export-oriented economy like Germany. During this time, the UK has lost market share across nearly all product categories – with the exception of ‘unspecified’ goods and arms sales – despite steady growth in global demand (right panel, an interactive version here).

The problem of falling British exports, it appears, is not due to a decline in global demand but rather a steady erosion in UK export competitiveness in the face of rising competition. This challenge, while shared by other European countries, has been uniquely exacerbated by Brexit, which has increased the relative costs of exporting overseas for British manufacturers. The result is a subdued export performance on a scale that is unprecedented in recent history.

A new geopolitical moment

The timing of Britain’s trade malaise could not be worse. Global trade is increasingly contested, with rising protectionism and geopolitical instability. Under the Trump administration, the US has introduced sweeping trade barriers and a significant source of uncertainty in the global landscape. While the deal struck between the British government and the White House may soften the immediate blow of US tariffs, British exporters will face higher trade barriers than before. Trump’s tariffs have had an unexpected immediate impact on British exports. Goods exports rose 3.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2025, driven by higher US exports as some businesses frontloaded their imports before the US president’s tariff announcement in March. Most notably, UK aluminium exports surged by an astonishing 587 per cent between the last quarter of 2024 and the first quarter of 2025.

What may be more significant for the UK than the direct impact of Trump’s tariffs are their second-order effects, as some imports will be diverted away from the US market, increasing competition in third country export markets. The volatility of the US dollar, in which over two-thirds of British exporters invoice, compounds the challenges.

All this should prompt serious reflection within Britain’s Labour government. While its diagnosis of the UK’s growth problem as a long-standing supply-side issue is valid, its prescribed remedies – unlocking investment, reforming planning and restoring macroeconomic stability – are necessary but insufficient. The external environment matters profoundly in a country where trade accounts for nearly two-thirds of its GDP. Labour ministers must pay close attention to how trade is shaping the UK’s growth trajectory.

Britain’s weak trade performance is not merely a cyclical blip but a structural issue that reflects a long-standing erosion of competitiveness in the goods sectors, further exacerbated by Brexit.

Acknowledging that Britain’s weak trade performance is not merely a cyclical blip but a structural issue that reflects a long-standing erosion of competitiveness in the goods sectors, further exacerbated by Brexit, is the first step. The second is recognising that delivering sustained growth is impossible without addressing this trade malaise. The third is understanding, in this particular geopolitical moment, that this cannot be done without more ambitious improvements to the UK’s most critical trading relationship – with the EU. The UK-EU reset deal, while it has the potential to improve certain practical aspects of trade, such as movement of food products and energy flows, is unlikely to make noticeable difference to the current growth trajectory.

The sooner Labour ministers confront these hard truths, the greater their chance of improving Britain’s growth prospects ahead of the next election.

Anton Spisak is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment