EU enlargement: Door half open or door half shut?

EU enlargement has spread peace and prosperity, but it has now stalled. The EU should keep the door open, and prepare countries for coming inside.

The European Union's enlargement after the Cold War is one of its most successful projects. It has helped to preserve stability in a region that experienced more than its share of conflict in the previous century, and it has brought prosperity to millions who had suffered decades of privation under communism.

The treaty on European Union says that the right to apply for membership is open to any European state which respects the EU's values and is committed to promoting them. But is that still true in practice? The EU is now at various stages of the accession process with six countries in the Western Balkans, plus Turkey; and Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine also aspire to join the Union. But few if any of the existing member-states are enthusiastic champions of any of these countries. Britain was once the leading proponent of expanding the EU, but the Brexit referendum has made the British government both less enthusiastic and less influential in the enlargement debate.

Since becoming European Commission President in 2014, Jean-Claude Juncker has consistently said that there would be no further enlargement during his term of office. In his 'State of the EU' speech to the European Parliament on September 13th, he again argued that no candidate was yet ready. He ruled out membership for Turkey for the foreseeable future, arguing that it was taking "giant strides away from the European Union" in relation to the rule of law, justice and fundamental rights. But he also stated firmly that the EU would in future have more than 27 members. French President Emmanuel Macron, in his ‘Initiative for Europe’ speech on September 26th, suggested that the countries of the Western Balkans could join the EU in some years, once the Union had been substantially reformed. He also acknowledged the strategic value of preventing them from aligning themselves instead with Russia, Turkey or other authoritarian powers.

Treaty on #EU says membership open to any Eur state which respects EU's values. Still true in practice?

The statements of Juncker and Macron emphasise that any further enlargement is at best some years away. This pause gives the EU and the states that aspire to membership a chance to consider what sort of relations they would like and could realistically aspire to in future. Obstacles to membership include lack of economic and political convergence between the EU and aspiring members, and lack of support for enlargement in existing member-states. If full membership of the EU is indeed far off, hard or even impossible to achieve in the foreseeable future, now may be the time to look for other ways to promote stability and prosperity in neighbouring European countries. Turkey poses a particular problem because of its growing authoritarianism and because so few EU member-states regard it as truly European.

In theory, both the countries of the Western Balkans (whether they have started accession negotiations or not), Turkey, and the three Eastern Partnership countries with association agreements with the EU should be converging with the EU. They should be adopting the acquis communautaire – the accumulated body of EU law – in relevant areas, meeting European standards, and becoming richer in the process.

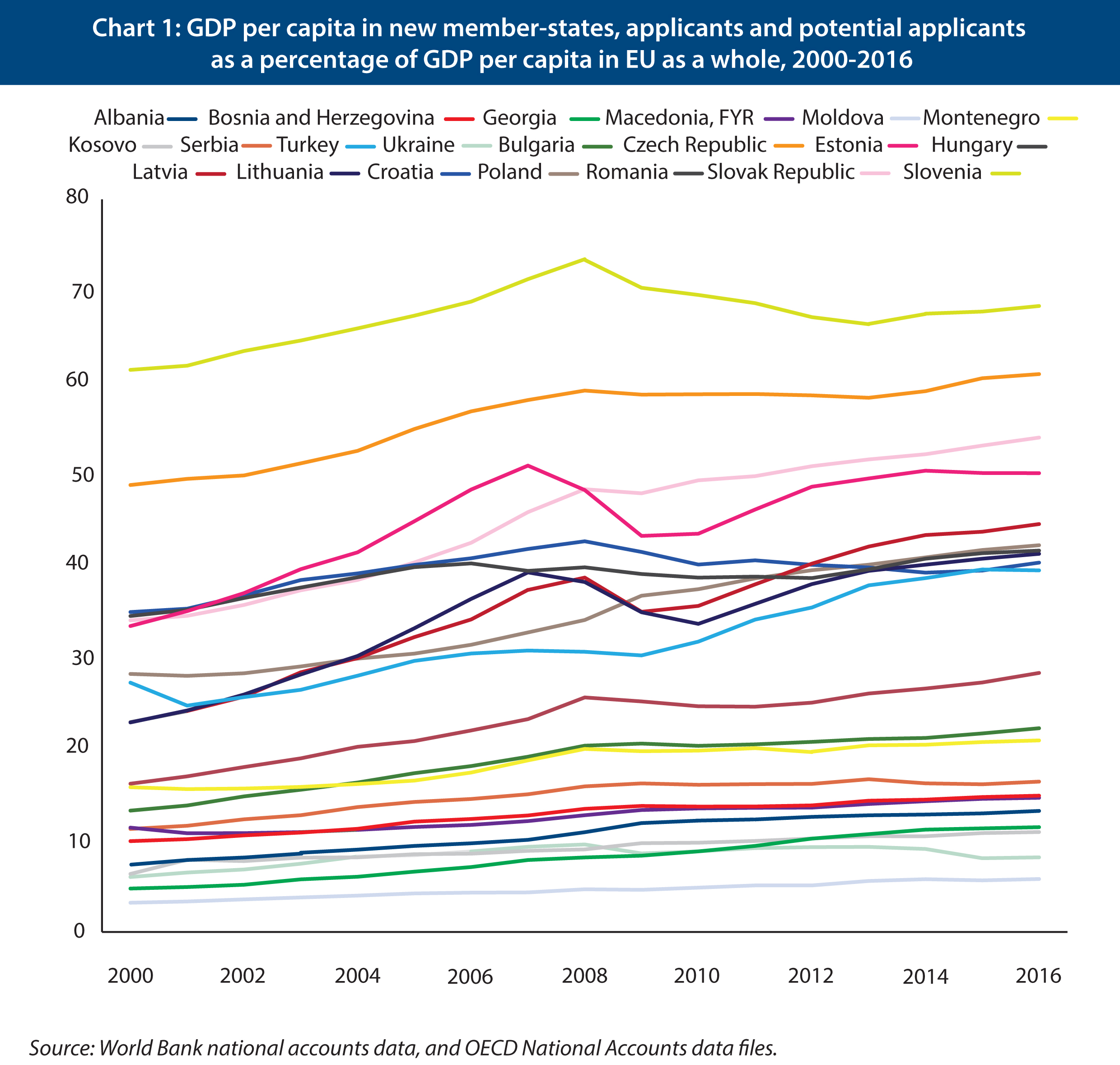

In relation to the economy, there is some progress in narrowing the gaps, but it is very slow. Chart 1 shows that since 2000 gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in both the countries that have acceded to the EU and those behind them in the queue has got closer to the EU average. But of the non-members, only Turkey has a higher GDP per capita than the poorest existing members (Bulgaria and Romania); and of the remaining applicants and potential applicants, all but Montenegro have GDP per capita below 20 per cent of the EU average. Two, Moldova and Ukraine, are below 10 per cent of the EU average.

EU reports on the progress that countries are making in adopting EU rules and standards paint a mixed picture, and sometimes seem to overplay their achievements. The 2016 report by the Commission on Turkey’s accession process for example stated that “Turkey reached some level of preparation to implement the acquis and the European standards” in relation to the judiciary and fundamental rights – even though the authorities detained more than 40,000 people, including around 150 journalists, in the wake of a failed coup attempt in July of that year.

Corruption a serious problem in aspiring mbrs. Georgia least corrupt, 44th on @anticorruption #CPI2016

One point on which the Commission and other sources of information agree, however, is that corruption is a serious problem across the potential future member-states. Georgia, which is judged to be the least corrupt of the group, is in equal 44th place on Transparency International’s ‘Corruption Perceptions Index’. Next comes Montenegro (64th equal), Serbia (72nd equal) and Turkey (75th equal – the same as the worst of the current member-states, Bulgaria). The remaining countries stretch all the way down to Moldova (123rd equal) and Ukraine (131st equal). In many cases the problems are getting worse, not better. Only Albania, Georgia and Kosovo were judged less corrupt in 2016 than in 2015. Macedonia fell from 66th place to 90th place – though the Commission’s report on the accession process does not reflect this deteriorating situation.

Public opinion across the EU is highly susceptible to scare stories about migration and about possible terrorist infiltration of the EU across porous borders. Governments and the Commission will struggle to persuade voters that they will benefit, even in the long term, from giving EU membership to relatively poor countries with high levels of corruption. The Netherlands provided a warning in 2016 of what might lie ahead: even the (false) suggestion that the association agreement with Ukraine might lead to eventual membership was enough to mobilise Dutch voters to block its ratification in a referendum. Any accession treaty would probably suffer the same fate in the current political climate.

Rebuilding support for enlargement will be a very long process. Support for the post-Cold War enlargement was in part emotional: as the countries of Central Europe transitioned from communism to democracy, there was a widespread sense that joining the EU represented a sort of homecoming for them. The then Czech President, Vaclav Havel, expressed this in a speech to the European Parliament in 1994, telling MEPs: “Europe was divided artificially, by force, and for that very reason its division had to collapse sooner or later”. Nowhere in the EU is there a similar feeling about the countries of the Western Balkans or Eastern Europe, still less Turkey. And Western European criticism of the state of human rights and governance in Hungary and Poland (in particular) even hints at some regret at the results of previous enlargements.

With populism on the rise in many parts of the EU, many mainstream politicians are wary of arguing in favour of enlargement. Neither Juncker nor Macron made an especially enthusiastic case for taking in new members. If enlargement is ever to start again, the EU will have to show that it can maintain control over migration (for example through extended transition periods before full freedom of movement); retain leverage in case of backsliding on the rule of law or human rights; and avoid making EU decision-making more cumbersome (in that respect, Macron’s proposal for a smaller Commission makes sense).

But EU leaders also need to start appealing to voters’ sense of justice, making the case that it is only right that countries that genuinely espouse European values, sometimes at great risk (as in Georgia and Ukraine) should have the right to join the EU when they meet the requirements for doing so. And they should not neglect practical benefits of enlargement either: as EU membership made new members richer, it would increase their propensity to consume goods and services from other member-states.

#EU needs to encourage & help neighbours to build up resilience in face of internal & external threats

The EU also needs to encourage and help its neighbours to build up their resilience in the face of internal and external threats. In the Western Balkans, that means more engagement by the Commission, the European External Action Service and national leaders to show that the EU still sees the countries of the region as future members. Macron’s warning about the efforts of Russia and Turkey to lure these countries away from Europe was well founded; the EU needs to make sure that populations there realise how much the EU contributes to their security and prosperity, and how little Moscow and Ankara have to offer by comparison. And it needs to work on exposing and preventing corruption in the aspiring members – including tackling money-laundering through the financial systems of EU member-states.

For Eastern Partnership countries, EU Commission officials already worry about the risk that countries like Georgia and Ukraine may rest on their laurels now that their association agreements with the EU have entered into force. The EU must continue to stress the economic and political benefits of fully implementing the association agreements, and creating a better environment for European investors. It can do more to support implementation of the agreements, including helping its partners to develop and carry out cross-government programmes to fulfil all the agreements’ requirements, and putting more advisers into ministries and agencies.

Ideally, the Union would also agree to offer Eastern Partners a long-term membership perspective, once they meet all the requirements. So far, however, that has been much too bold a step for most member-states. By grabbing territory in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, Russia has made it both politically unattractive and practically complicated for the EU to offer any of them membership. No-one wants to replicate the problems caused by the fact that the government of Cyprus does not control all of its territory. At the very least, the EU should find ways to increase political contacts with its three partners, to reassure them that they are still on Europe’s radar; and if possible it should find a way to repeat the statement in the Foreign Affairs Council conclusions of March 2014 that the association agreement “does not constitute the final goal in EU-Ukraine cooperation” and extend it also to Georgia and Moldova.

Ideally, #EU wd offer Eastern Partners long-term membership perspective, once they meet all requirements

More practically, the EU should start thinking about its future relations with these countries, once they have implemented their association agreements. If, as seems likely, existing member-states will still be reluctant to start formal accession negotiations, the EU should consider whether it could further open its markets to goods and services from the three countries. It should also consider offering some limited right to work to their citizens, as it did in the ‘Europe agreements’ signed with the Central European countries in the 1990s. It could increase technical assistance. In effect, it might think of creating something like the European Economic Area, but adapted to help a much poorer group of countries integrate with the EU. Over time, as they continued to adopt more of the acquis and become more prosperous, public opinion in the rest of the EU might become less hostile to their eventual membership, especially if the EU put in place safeguards against failure to continue reforms as it did in Bulgaria and Romania, as part of the conditions for their accession.

That leaves Turkey. For reasons of security and because of its role in stemming the flow of migrants from the Middle East to the EU, few member-states want to put a stop formally to accession negotiations. Some in Brussels suspect that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan would like to goad the EU into doing so, forcing the Union to take the blame. But with Turkey’s swing away from the EU and towards authoritarianism, its human rights problems, and its apparent willingness to challenge EU influence in the Balkans, there is also no possibility of moving forward. For now, the EU seems to have little choice but to keep the door ajar and hope for better days. It can at least say to Ankara that Turkey is not being discriminated against: for now, no-one else is getting in either.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

Your (adapted) EEA proposal is spot on and I could not agree more.

Add new comment