Europe must choose: Multiculturalism or stagnation?

An increasingly multi-ethnic society would safeguard Europe’s prosperity – or it can opt for nativism, labour shortages and higher taxes.

The radical right is likely to make big gains in the European Parliament next month, with the ‘great replacement’ theory becoming increasingly influential. The theory holds that liberal elites are promoting immigration from outside Europe to undermine ethnic and cultural homogeneity. Many politicians on the centre-right have chosen to accept the premise of this civilisational rhetoric, rather than confront it. Ursula von der Leyen made the Commission’s migration post ‘the Vice-President for Promoting the European Way of Life’. In France, the leaders of the centre-right Républicains party decry mass immigration and the “submersion” of France. Germany’s Christian Democrats said “all those who want to live here must recognise our dominant culture without any ifs or buts” in their draft manifesto, published last December. Meanwhile, Britain’s Conservatives are detaining asylum-seekers in the hope of deporting them to Rwanda.

The practical problem with this lurch to the nativist right is that Europe is ageing rapidly, and fewer immigrant taxpayers mean higher taxes on workers, to pay for pensions, healthcare and other public services for the elderly. That is well known, but what is less understood is the limited extent to which free movement of people within Europe and higher employment rates will help alleviate the scarcity of labour.

Mainstream politicians need to confront nativist parties, not accept their premises, immigration is needed to keep the working age population stable.

Free movement has largely been a win-win for Europeans. Sending countries have lost workers, but expats have received big rises in income from working in other countries, with many sending home remittances that substantially raise spending in their home country. Wages and tax revenues in Central and Eastern Europe have risen rapidly, in large part because of the single market, despite workers leaving. Receiving countries in Northwestern Europe have benefited from higher employment and larger tax bases, raising services output and helping to pay for pensions. The loss of workers has been controversial in Central and Eastern Europe, and in his recent report on the single market former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta argued for reforms to promote “the freedom to stay”. But that appears to be happening without policy change: the rise in numbers taking advantage of free movement has slowed – in part because of the convergence in living standards. Employers are increasingly looking to workers from outside Europe to fill vacancies. The choice between ethnic homogeneity and prosperity is set to become more acute over the next decade.

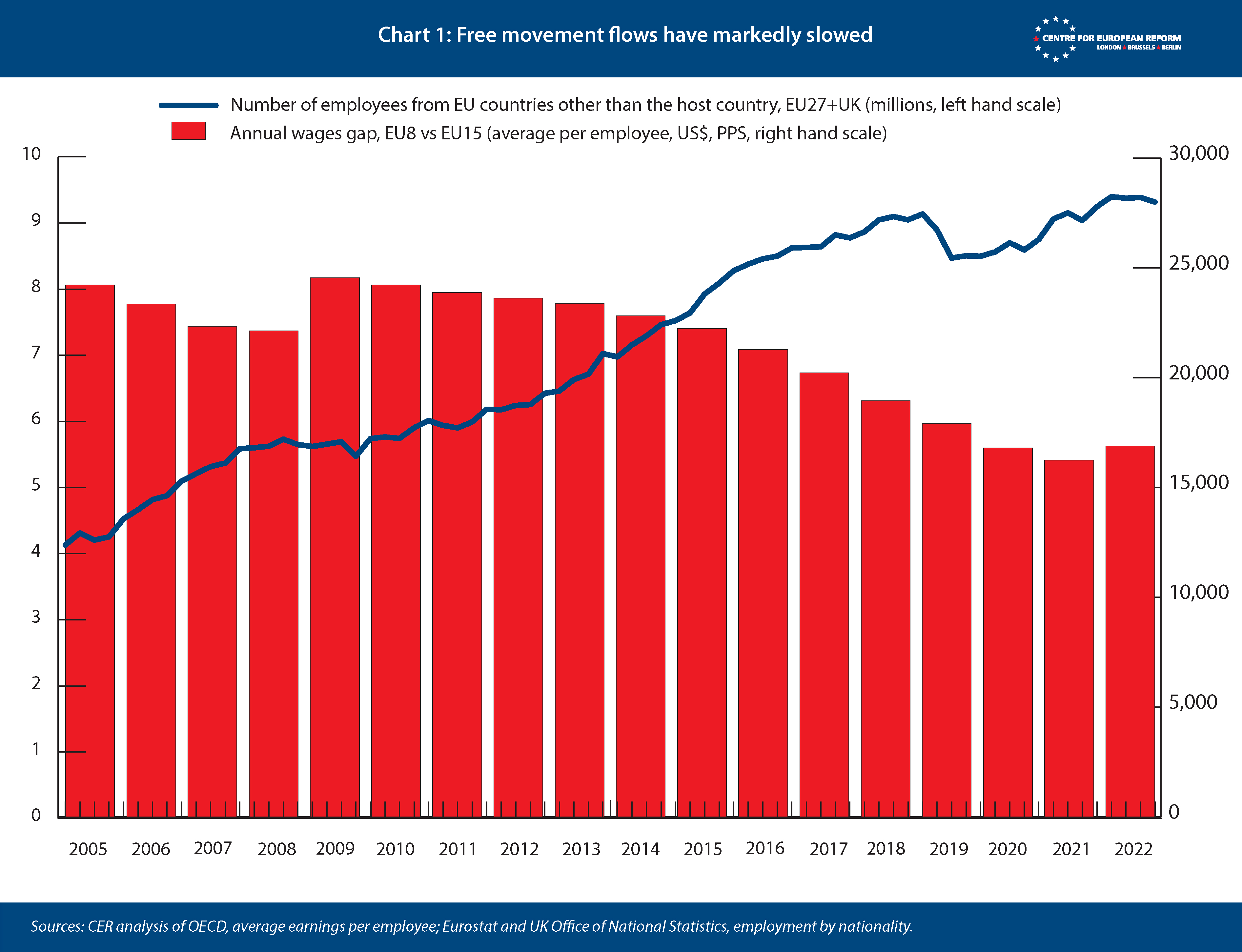

Chart 1 shows the increase in employment of EU nationals from another member-state has slowed markedly since 2016, with only a small rise of 200,000 since 2019. The difference in wages between newer and older member-states has fallen substantially, and is likely to fall further in the future, if forecasts of relatively fast growth in Central and Eastern Europe are right. This has reduced incentives for Europeans to move. So have the EU’s improved macroeconomic policies: high unemployment during the euro crisis led many Southern Europeans to leave for jobs elsewhere. No central bank can control the economic cycle, but the self-defeating policies of the European Central Bank in the 2010-2012 period are unlikely to be repeated. By raising interest rates in 2010 and 2011, and then refusing to stand behind government debt, the bank raised unemployment, triggering deflationary pressures, and failed to meet its inflation target. Ukraine joining the EU could give migration within Europe a boost, but the war must be won first, and accession before 2030 is unlikely.

As incomes have converged between east and west, free movement has slowed. Northwestern Europe will need more immigrants from outside Europe.

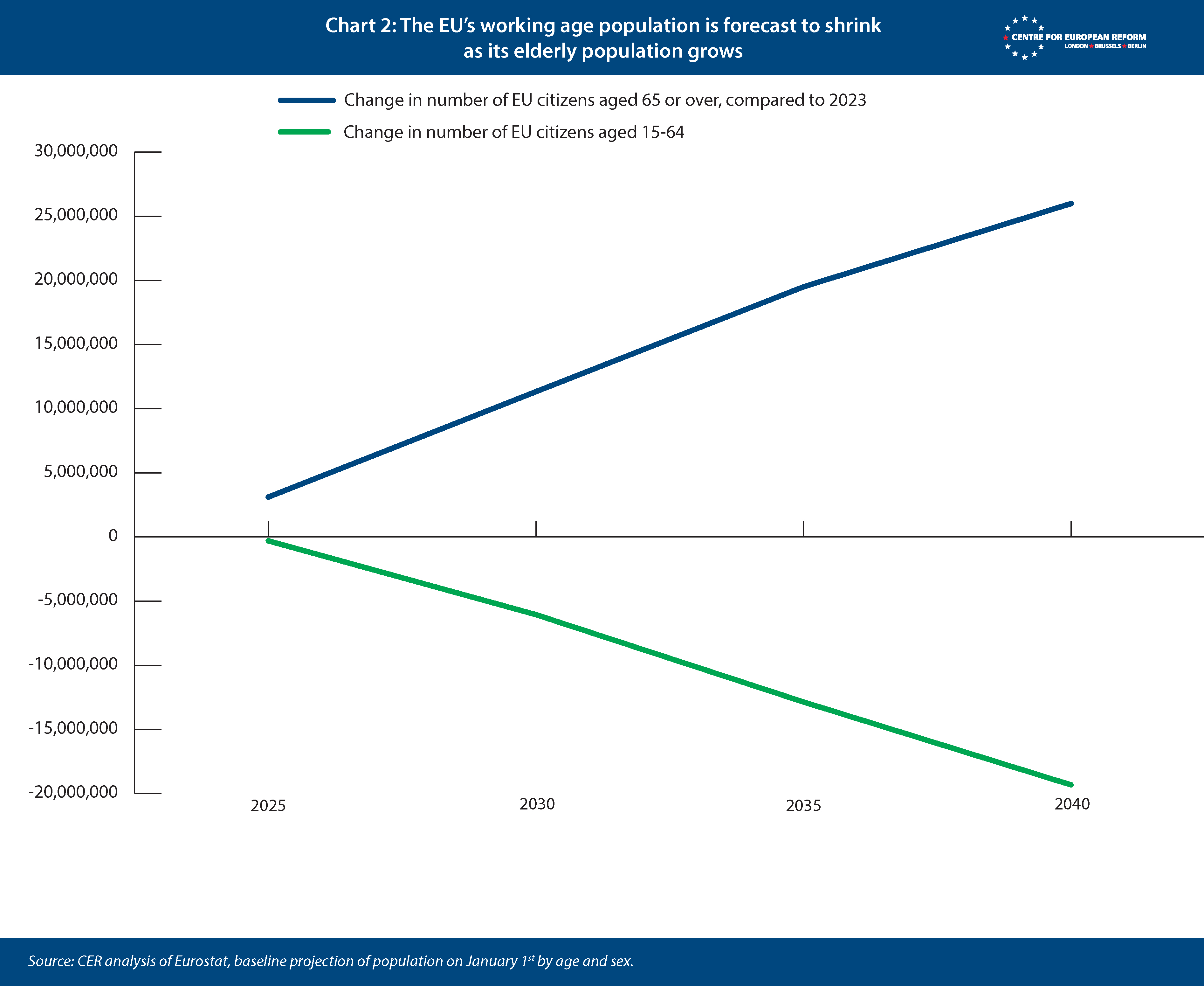

Cajoling existing European residents to work harder and longer would help, but it is unlikely to be enough to offset the ageing process. Take an almost impossibly hopeful scenario – that all 27 EU member-states managed to achieve the 82 per cent working-age employment rate of the EU’s star performer, the Netherlands. That would add 34 million employees. But the number of EU citizens aged over 65 is forecast to grow by 25 million by 2040, even including trend immigration rates (with the caveat that population projections are very imprecise, Chart 2). Meanwhile, the number of Europeans aged between 15 and 64 is projected to fall by 20 million.

Could people not work until they are older? Many European countries have announced that retirement ages will rise in the future, but there are limits. While life expectancy has risen, most Europeans will suffer from a serious medical problem by their mid-60s. Even healthy older workers will not be willing or able to fill roles that involve a lot of physical labour. Those who are skilled will be unwilling to move into less-skilled jobs, which are often taken by younger people, including immigrants, and most will be unwilling to invest in new skills for a few extra years of work.

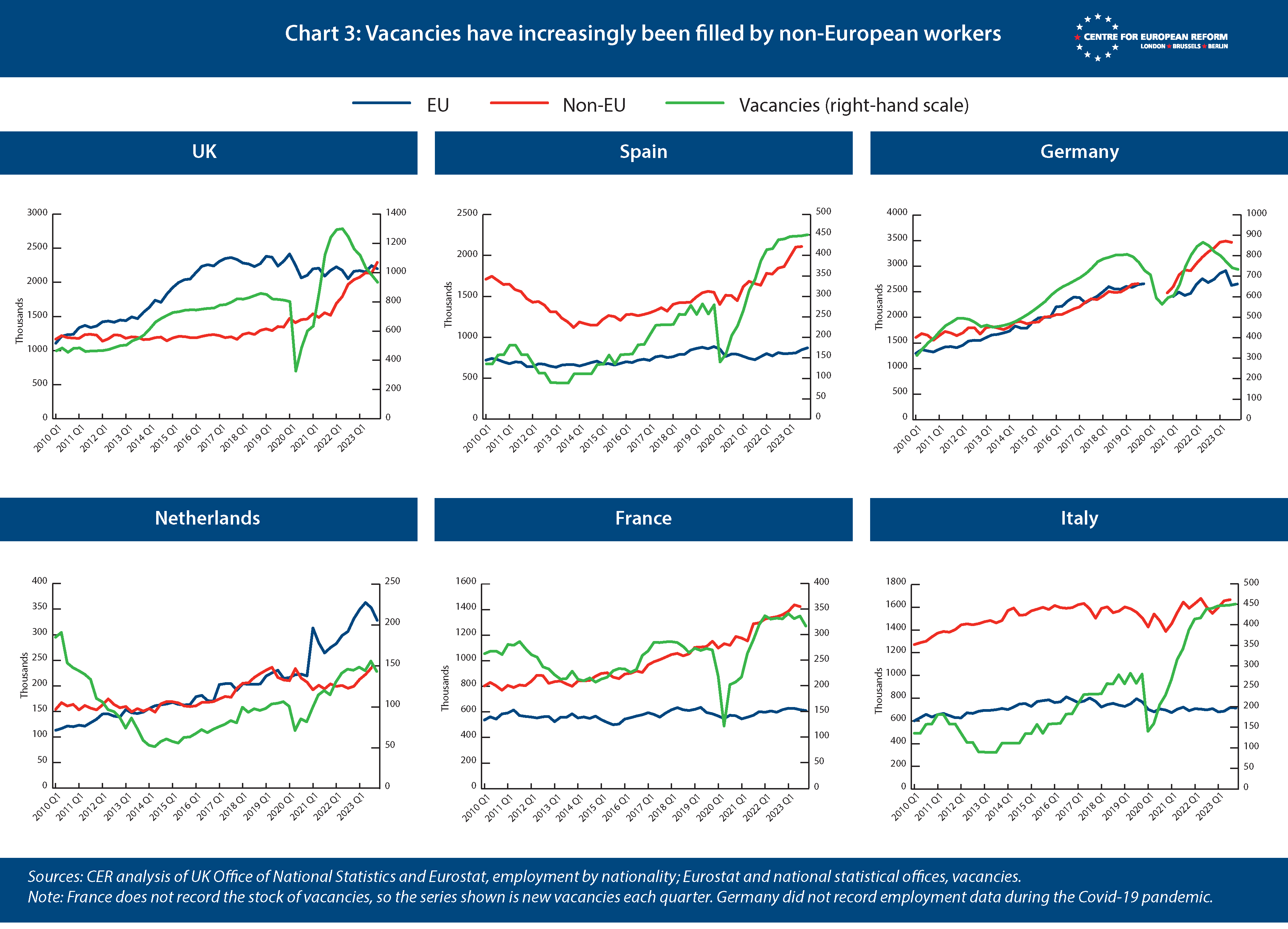

As a result of slowing free movement and ageing, employers are already turning to people from outside Europe to fill jobs. Chart 3 shows employment of non-EU and other EU nationals in countries in Western Europe that have had large net immigration over the last 15 years. In all of them, bar the Netherlands, the number of other EU nationals in work (as shown by the orange line) has stagnated – in the UK and Germany’s case since 2016 or 2017, and from an earlier date in Spain, France and Italy. Apart from investment in labour-saving technology, employers have increasingly dealt with tight labour markets by employing non-Europeans. Job vacancies increased after the euro crisis – as did ageing, with the number of working-age Europeans peaking in 2009. As the number of vacancies (green line) grew, the number of non-EU nationals in employment grew too (again, bar the Netherlands, and also Italy). This process accelerated after the pandemic, when a surge in retirements, ill health, people switching jobs and emigration led to big rises in jobs taken by workers from outside Europe.

As Europe ages and free movement has slowed, vacancies have increasingly been filled by non-EU workers in the main receiving countries.

Most politicians on the centre-left and centre-right recognise that immigration is needed to ease demographic pressures, and have sought to focus on tougher – and often inhumane – asylum rules, in the hope that stricter border enforcement will provide political cover for higher regular immigration. Even Italy’s prime minister Giorgia Meloni, who projects an anti-immigration stance, has increased the number of work permits for non-EU foreign workers. But radical right parties are increasingly challenging the mainstream consensus. Right-wing members of parliament amended Emmanuel Macron’s immigration law to include immigration quotas last year (although those amendments were ultimately quashed by France’s constitutional court). Britain and Sweden have both recently raised minimum salary thresholds that foreign workers must exceed to be eligible for a work permit.

Europe will become less white and more multicultural in the future, unless the right succeed in reducing immigration from outside the continent. This poses an acute political dilemma for mainstream politicians of the centre-right and centre-left. They can challenge the nativists, asking tough questions about labour shortages, the tax burden on working age people, and the quality of health and elderly care systems without higher rates of immigration from countries outside Europe. Or they can seek to borrow the nativists’ tunes, but at the risk of being overtaken by them, as has happened in elections in Italy, the Netherlands and France. Those of us who welcome the economic and cultural vigour that immigrants bring should hope that mainstream politicians find some courage.

John Springford is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Comments

I think most people would rather stagnation than to destroy their homelands all for the sake of "gdp go up".

Add new comment