Why the EU's recovery fund should be permanent: Country report - Poland

COVID-19

While the impact of the first wave of Covid-19 infections in spring 2020 was small in Poland, the country suffered from two large waves peaking in November 2020 and in May 2021.

The fiscal policy response in 2020 totalled 5.3 per cent of GDP and included numerous measures, from wage subsidies and boosted unemployment benefits to emergency healthcare spending and transfers to local governments. On top of this, the government set up credit guarantees and micro-loans for entrepreneurs and the national development agency funded additional liquidity programmes for businesses.1

The economic impact of the crisis has been smaller in Poland than in other EU countries: GDP dropped by 2.7 per cent in 2020, but the OECD projects that GDP will recover by 3.7 per cent in 2021, attaining its pre-pandemic level by the end of the year.2 However, the pandemic could increase the already high level of inequality.3 Temporary workers and small firms have been hit harder by the crisis, and losses in employment have been higher in poorer regions.4

Long-term economic performance

Poland’s economy has grown steadily in the past twenty years: 2020 was the first year since 1991 where year-on-year real GDP declined. However, large inequalities between regions persist: GDP per capita in Warsaw is almost 300 per cent of the national average, whereas in the poorest region, Przemyśl, this figure is 53 per cent.5

The structure of the economy has evolved since Poland shifted from a centrally planned to a market economy after 1991. Productivity increased, mostly thanks to a burgeoning service sector and the internationalisation of manufacturing.6 However, manufacturing is largely focused on low value-added goods. Barriers to productivity growth include labour shortages (due to an ageing population and the low participation of women in the workforce, itself hindered by insufficient childcare), the complex business environment and the slow uptake of digital technologies among SMEs.

Recent investment, partly funded by EU transfers, has also helped to raise productivity, for instance by improving the road network and other infrastructure. But more needs to be done to modernise infrastructure: maintenance of existing roads should be improved, along with local public transport and railways, and the existing vehicle fleet should be renewed to curb high air pollution in urban areas.

Greenhouse gas emissions

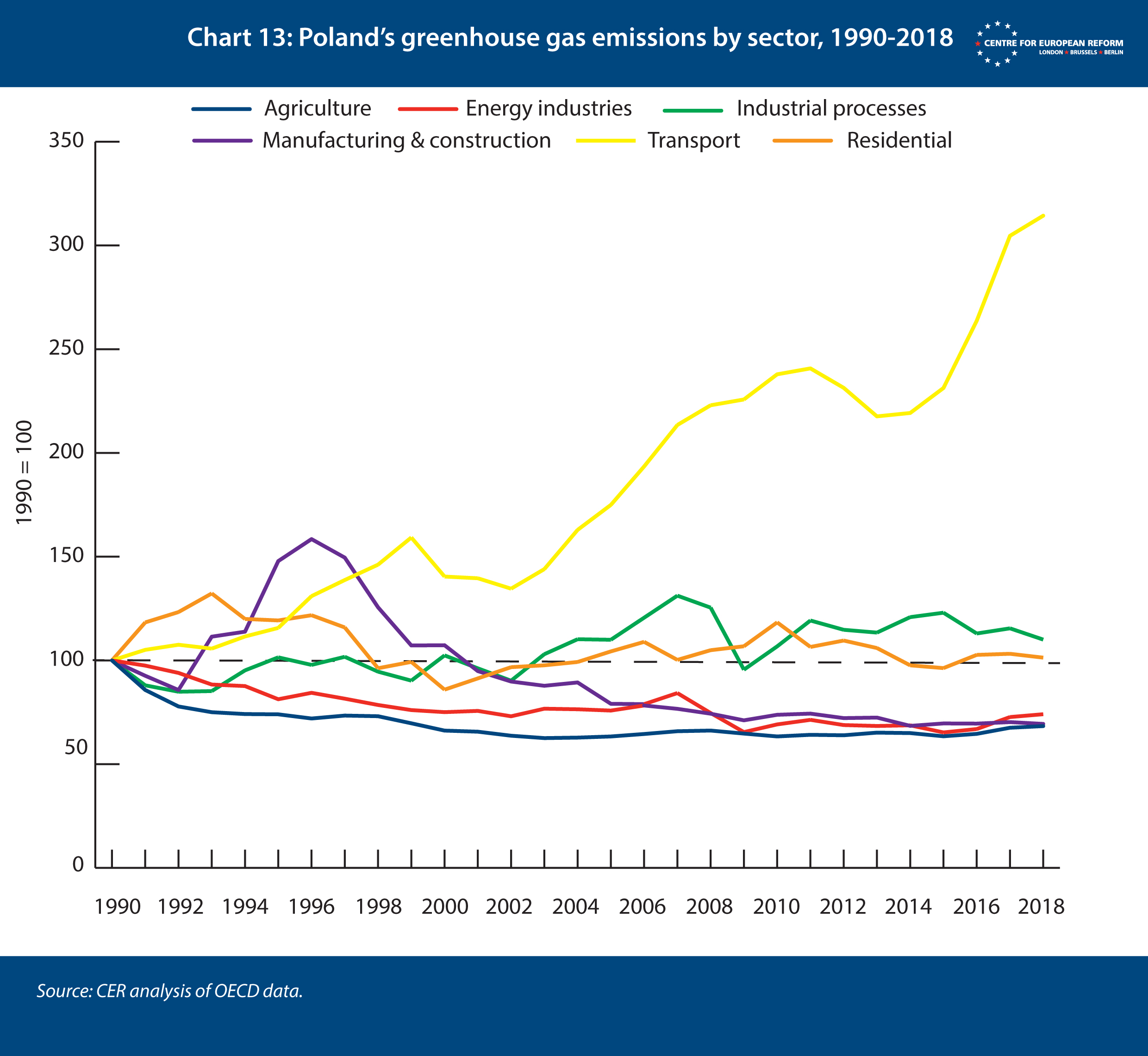

Poland’s greenhouse gas emissions fell by 13 per cent between 1990 and 2018. Even so, in 2018 Poland’s emissions from sectors excluded from the EU ETS were higher than their annual allocation. These include transport and buildings, and are governed by the EU’s effort-sharing regulation, which sets member-states’ emissions targets, but leaves them in control of how emissions are curbed.7 Specifically, transport emissions have more than tripled since 1990 (see Chart 13).8

Poland draws 90 per cent of its total energy supply from fossil fuels. Coal is the most-used energy source: it makes up 44 per cent of all fossil fuels used in Poland and three-quarters of all energy generation in Poland.9 The country wants to reverse this trend: the recently approved ‘Energy Policy of Poland to 2040’ sets the target of a maximum of 56 per cent of electricity generation from coal for in 2030.

To address high air pollution levels, Poland also aims to provide all households with district heating and low-emission energy by 2040 – a major overhaul, because residential heat is currently responsible for more than half of the country’s coal consumption.

Poland’s recovery plan

Poland is seeking the full amount of grants it can receive under the RRF (€23.9 billion), but it has only applied for part of the loans it is entitled to receive (€12.1 billion). The plan aims to overcome the challenges holding back Polish economic development, which can broadly be grouped into three categories:

- Economic environment: low productivity; a weak investment climate and consequent low level of private investment; low uptake of digital technologies; weak transport infrastructure; weaker public finances.

- Social conditions: an ageing population, which may result in labour shortages; low quality of the health service and problems with access to it; uneven regional levels of development and growth potential, which COVID-19 has worsened.

- Energy transition: a dependence on coal, both in the country’s energy mix and for jobs in mining regions; outdated and limited public transport infrastructure (both long-distance rail and urban networks).

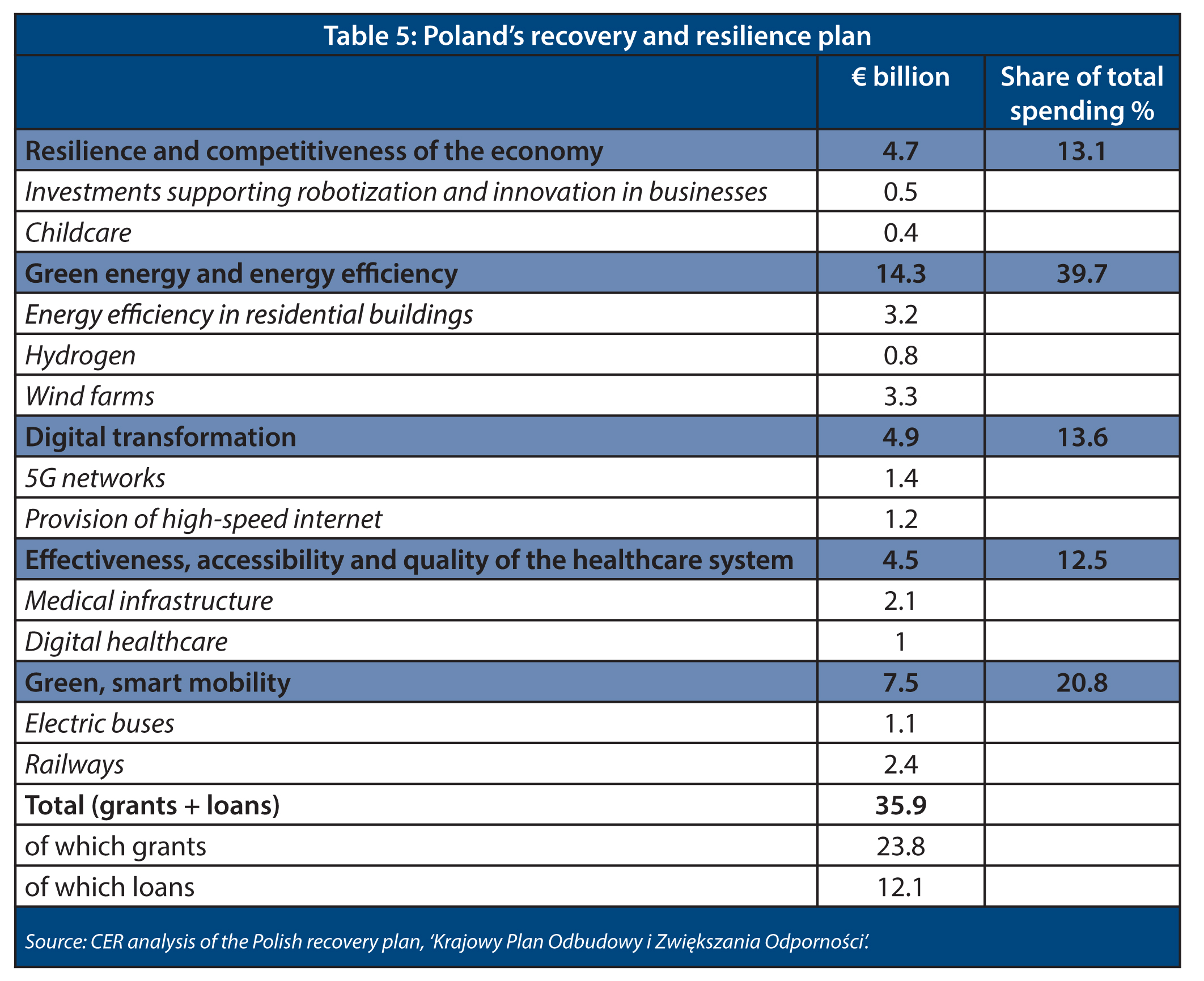

Poland’s recovery plan outlines five investment priorities to solve these problems: resilience and competitiveness of the economy; green energy and the reduction of energy intensity; the digital transformation; effectiveness, availability and quality of the health-care system; green mobility. Each of these investment areas includes interventions for social and territorial cohesion. Table 5 provides the share of total spending on each priority.

To boost productivity and competitiveness, Poland’s national recovery plan wants to improve connections between businesses and research institutes. The government has also put forward fiscal incentives such as tax credits for innovation. To deal with labour shortages, the Polish government wants to allow for continued work beyond retirement age, do more to retrain those who are unemployed and facilitate the access of foreigners to employment. The plan also includes reform of vocational education and lifelong learning, to strengthen the link between schools and the labour market.

The plan insists that Poland’s energy transition will have to be gradual, and sets a deadline of 2049 for the full phase-out of coal. Coal mining is very important in Poland, both in economic and political terms. The sector accounts for 83,000 jobs and the Polish government will have to tread carefully with powerful industry and trade union bosses, in order to avoid social unrest. Ahead of the far-off coal phase-out, the recovery plan envisages natural gas as a transitional energy source; and the government has agreed substantial severance payments for miners. The plan also includes reforms to facilitate investment in renewable energy.

A range of reforms and investments aim to increase internet use, particularly by giving citizens greater access to public services online. For this, Poland will invest in digital skills and in network infrastructure (5G, high-speed internet), and remove red tape that is slowing down infrastructure development.

Poland plans to reform the hospital sector and strengthen primary healthcare, based on an analysis of health needs that will consider demographic and epidemiological trends and regional differences.

The plan also includes investments to replace older, inefficient rolling stock used on the rail network. The government will also mandate clean transport zones in urban areas.

At the time of publication, the Commission has still not approved Poland’s recovery plan, amid growing tensions between Brussels and Warsaw over the rule of law. The Commission has linked the disbursement of the funds to the Polish government changing judicial reforms that have politicised the country’s courts.10 Poland will not receive funds until the Commission approves the plan. Among plans sent to the Commission, only Poland and Hungary’s recovery plans have yet to be approved.

2: OECD, ‘Economic Outlook’, May 2021.

3: Pawel Bukowski and Filip Novokmet, ‘Within a single generation, Poland has gone from one of the most egalitarian countries in Europe to one of the most unequal’, LSE EUROPP blog, December 2nd 2019.

4: OECD, ‘Economic survey of Poland’, December 2020.

5: Polish recovery plan, ‘Krajowy Plan Odbudowy i Zwiększania Odporności’.

6: OECD, ‘Economic survey of Poland’, December 2020.

7: EEA, ‘Trends and projections in Europe 2020. Tracking progress towards Europe’s climate and energy targets report 2020’, 2020.

8: IEA data, ‘Total final consumption by sector, Poland 1990-2018’, Poland key energy statistics 2018.

9: IEA data, ‘Total energy supply by source, Poland 1990-2018’, Poland key energy statistics 2018.

10: ‘Poland warned no EU recovery funds without judicial reform’, Financial Times, September 9th 2021.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2021

This paper is published in partnership with the Open Society European Policy Institute.

View press release

Download full publication