Why the EU's recovery fund should be permanent: Country report - Italy

COVID-19

Italy has been among the European countries hardest-hit by COVID-19, having suffered a particularly harsh first wave in spring 2020. A nationwide lockdown was introduced on March 9th. Between mid-March and mid-May 2020, the government implemented a range of fiscal packages amounting to over €860 billion, covering support for businesses to freeze layoffs, deferred tax payments as well as additional funds for healthcare.1 The economy contracted by 8.9 per cent in 2020.2 The OECD foresees 4.5 per cent GDP growth in 2021.3 While both existing and emergency employment protections stopped most workers from being laid off during lockdowns, temporary workers and the self-employed have been particularly badly hit by the economic fallout of the pandemic. These workers are often young and female, and these groups are both priorities in Italy’s recovery plan.

Partly due to disagreements on how to spend RRF funds, the government led by the populist Five Star party’s Giuseppe Conte collapsed in January 2021. It was replaced by a government including politicians from across the spectrum and technocrats, led by former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi. Draghi’s government has now been tasked by parliament to design and oversee the roll-out of the recovery plan and implement the much-needed, if unpopular, reforms that will be required to unlock access to EU funds.

Long-term economic performance

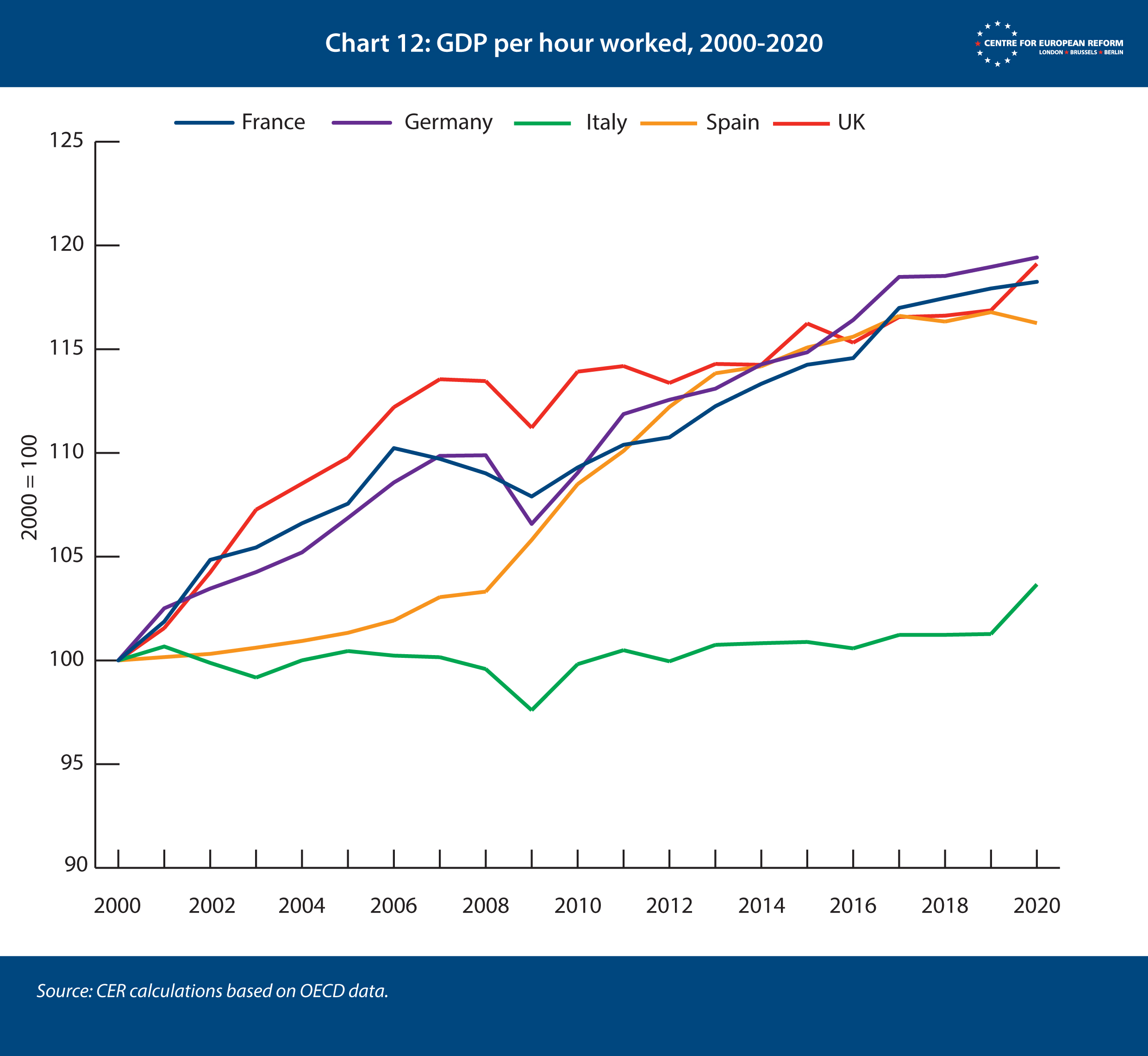

Italy’s long-term economic stagnation is partly explained by enduring structural weaknesses, which the Recovery Plan aims to address. The country is also highly geographically unequal, with the Mezzogiorno, or South of the country, being much less developed than the North. As illustrated in Chart 12, productivity growth has been flat for about two decades – a trend that coincides with a slowdown in public and private investment since 1999.4 Female employment is low, which can be linked to patchy childcare provision. Vocational education levels are below OECD averages.5 The economy has still not fully recovered from the financial crisis and ensuing austerity policies, with GDP per capita still below pre-crisis levels.6 While the unemployment rate has been falling since 2014, in 2019 it was still 10 per cent, with 18 per cent of young people not in education, employment or training.7

Greenhouse gas emissions

Italy’s greenhouse gas emissions dropped by 17 per cent between 1990 and 2018, well on the way to its 2020 objective.8 The residential sector and the transport sectors have seen growing emissions: in 2019, Italy had the second highest number of cars in the EU.9 The 2011 housing census indicated that Italy’s housing stock is older than the EU average, with more than half built between 1946 and 1980.10 Greenhouse gas emissions from the manufacturing and energy industries have dropped by between 40 and 30 per cent: the first trend is explained by the slow-down in economic activity and increased efficiency, particularly in the chemicals sector, whereas the second trend is due to the shift towards natural gas and renewable energy.11 In 2019, renewable energy supplied 18 per cent of final energy consumption.12

Italy’s recovery plan

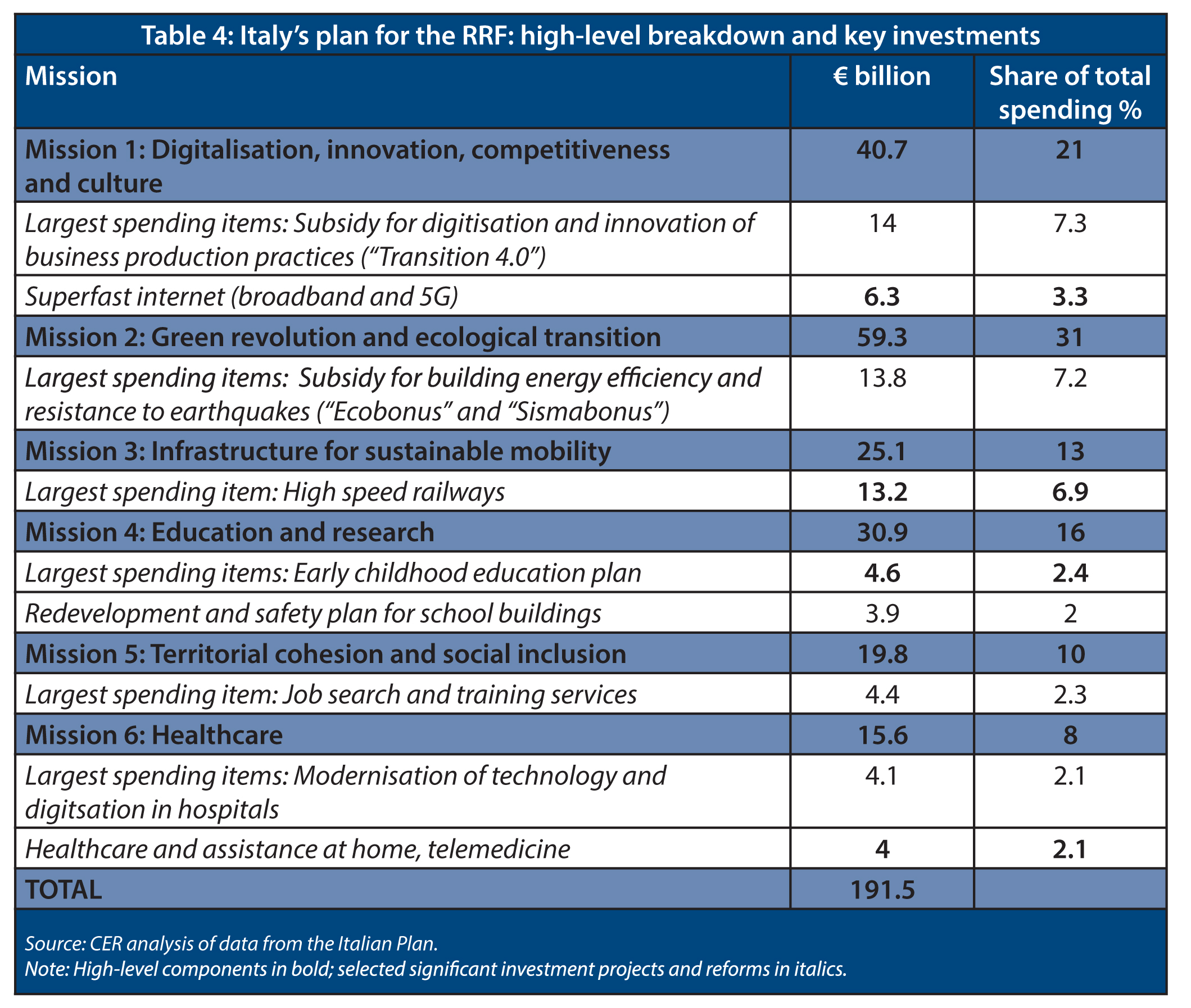

Italy plans to make full use of both the grant and the loan portion of the RRF – respectively €68.9 and €122.6 billion, for a total of €191.5 billion. This is by far the largest investment programme in the EU. These will be distributed across six priority areas, or ‘missions’. As per the RRF’s rules, the priority areas of green and digital transitions attract about 40 per cent and 27 per cent of funds. The rest of planned investments are divided between education and research, territorial cohesion and social inclusion, and healthcare (see Table 4). Cross-cutting priorities are improving the participation of women and youth in the workforce, and reducing regional inequalities, particularly with respect to the Mezzogiorno.

The single largest investment item, at €14 billion, is the so-called ‘Transition 4.0’ plan, which aims to boost business investment in R&D and skills. The success of this programme will depend on businesses’ demand for these funds and their ability to spend them wisely.

The largest slice of climate funding will subsidise households’ energy efficiency improvements, through tax credits (€13.8 billion). Municipalities will receive €6 billion to improve the energy efficiency and safety of public buildings and guard against flooding and other climate risks. The success of these subsidies will depend upon improving the confusing rules for households, and the bureaucracy involved in checking whether they are eligible.13 The limited number of specialised workers and shortages of sustainable construction materials might slow down uptake.

The government will spend €13.2 billion on high-speed railways: while better connections to neighbouring countries and to the Mezzogiorno are welcome, regional railway networks deserved greater attention, because reducing car use should be a priority. Instead, regional railways received less than €1 billion. On the other hand, Italy is making sizeable investments in local sustainable transport (€8.6 billion), including subway and tram lines in key metropolitan areas as well as better cycling infrastructure and new buses, with the aim of shifting at least 10 per cent of commuting in metropolitan areas from private to public transport.

Investment in renewable energy sources is comparatively low, with about €6 billion in total, of which €2 billion is devoted to biomethane. The focus is on encouraging the scaling-up of new energy sources, such as offshore wind. Recycling and other ‘circular economy’ solutions are somewhat neglected in the plan, with most funds directed to the improvement and construction of waste management and treatment plants, particularly in the South.

Early childhood education is inadequate in Italy and is a barrier to women’s participation in the workforce. The plan aims to add 228,000 childcare places to the existing 355,000.14 Improved local healthcare services are also needed, given Italy’s ageing population: the government plans to create over 1,200 local healthcare centres (‘Case della Comunità’) and shift to healthcare provision in the home as far as possible.

Draghi will try to implement several important structural reforms, which the EU has made a condition of Italy obtaining all of the RRF funding. The broadest reforms included in the plan are those addressing public administration and justice. The public administration reform includes a modernisation of staff recruitment procedures (focusing on technical and soft skills) and of performance evaluation, along with investments in the training of civil servants. The complex justice reforms aims to speed up trials, in part by using digital technology for some legal cases.

The scale of Italy’s plan is appropriate, given the structural issues that have been holding back the country. The flipside to that is a vast and fragmented set of investments, paired with gigantic reform efforts. Italy has always struggled with political stability and absorption of EU funds, so a successful investment and reform programme will depend both on finding convergence in parliamentary politics, and on careful implementation on the ground.

2: Bank of Italy, ‘Relazione annuale sul 2020 in sintesi’, May 31st 2021.

3: OECD, ‘Italy Economic Snapshot’, consulted in May 2021.

4: ‘Piano nazionale di ripresa e resilienza’, Italy’s recovery plan, 2021.

5: OECD, ‘Economic policy reforms 2021: Going for growth’, 2021.

6: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.

7: International Labour Organisation, ILOSTAT database.

8: OECD statistics, Greenhouse gas emissions data: National Inventory Submissions 2021 to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, CRF tables), and replies to the OECD State of the Environment Questionnaire.

9: Eurostat, ‘Passenger cars in the EU’, data extracted in September 2021.

10: Eurostat, ‘Statistics on housing conditions’, data extracted in November and December 2017.

11: Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA), ‘Italian Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2019. National Inventory Report 2021’, 2021.

12: Eurostat, ‘Renewable energy statistics’, data extracted in December 2020.

13: Kira Taylor, ‘Italy’s celebrated building renovation scheme hits a snag’, Euractiv, April 21st 2021.

14: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, ‘L’offerta comunale di asili nido e altri servizi socio-educativi per la prima infanzia’, press release, October 20th 2020.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2021

This paper is published in partnership with the Open Society European Policy Institute.

View press release

Download full publication