Why the EU's recovery fund should be permanent: Country report - Greece

COVID-19

While Greece managed to avoid a large first wave of Covid-19 infections by locking down early in spring 2020, it suffered from two further waves – and two further lockdowns – in November-December 2020 and in April-May 2021. Most activities re-opened in mid-May 2021.

In 2020, government support to the economy amounted to €23.5 billion (13.7 per cent of GDP).1 This involved emergency support for the healthcare sector (such as hiring extra staff and reducing VAT on protective gear) and providing assistance to hard-hit individuals and businesses, respectively through transfers (such as cash stipends and extended unemployment benefits), and liquidity support (such as loan guarantees and deferred tax payments).

Despite the government stimulus, Greece’s economy contracted by 8.2 per cent in 2020. While the OECD forecasts GDP growth to reach 3.8 per cent in 2021 and 5 per cent in 2022, GDP per capita is forecasted to reach pre-crisis levels only after mid-2022.2

Long-term economic performance

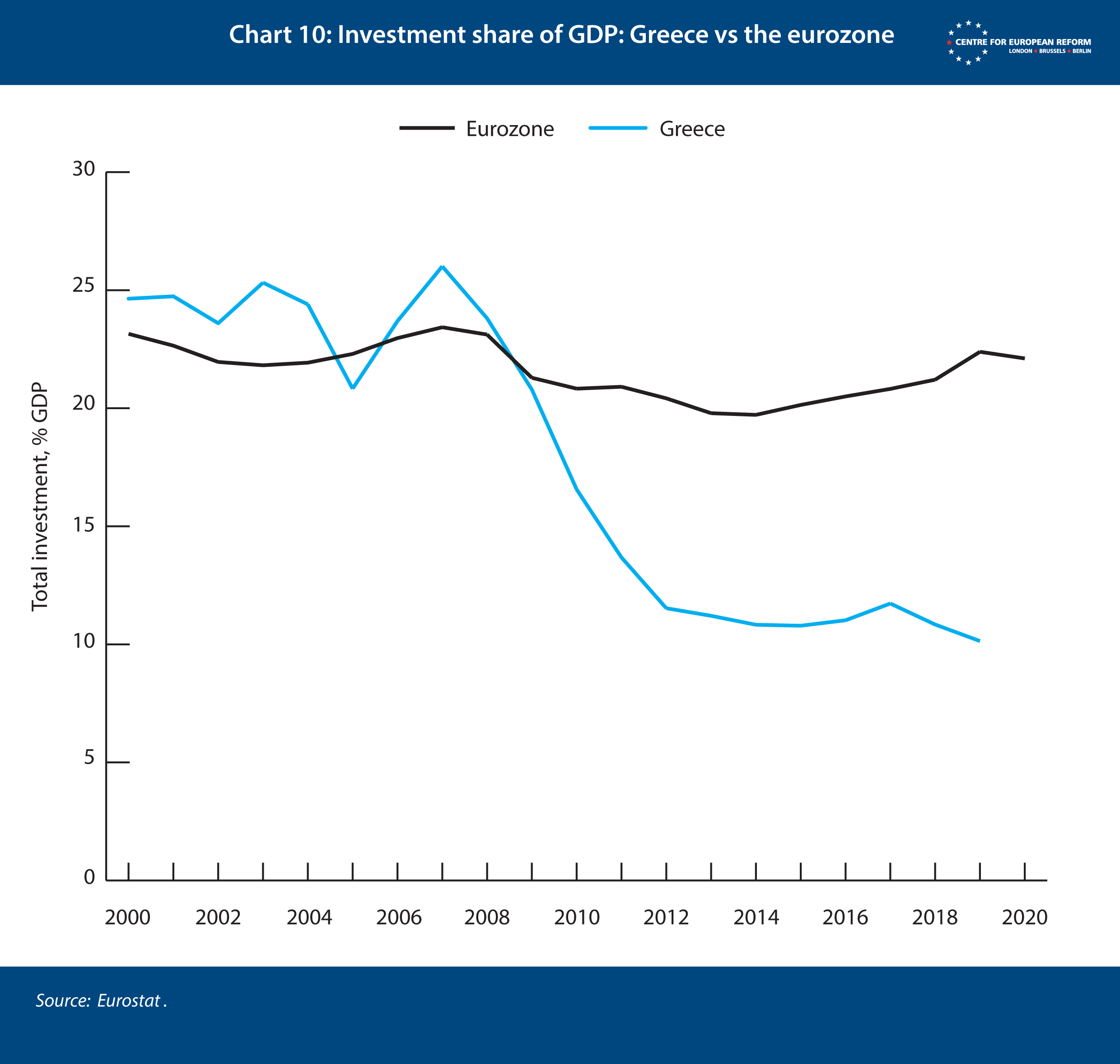

From 2017, Greece’s economy had started to recover from its long slump after the euro crisis. It achieved a 1.9 per cent annual growth rate in 2019. Bailouts by the EU and the IMF, and the austerity programme had led to an improvement in the primary balance of 1.5 per cent of GDP between 2009 and 2016.3 However, GDP in 2019 remained a quarter below its 2007 peak, and total investment had significantly fallen as a share of GDP since 2008 (see Chart 10). Employment remains low relative to the OECD average, particularly among women, and this translates into high poverty rates.

To improve productivity growth, Greece needs substantially higher investment in physical and human capital. Companies need to adopt new technologies, and government needs to improve skills provision and employment services to improve matching between job-seekers’ and employers’ needs.4

Greenhouse gas emissions

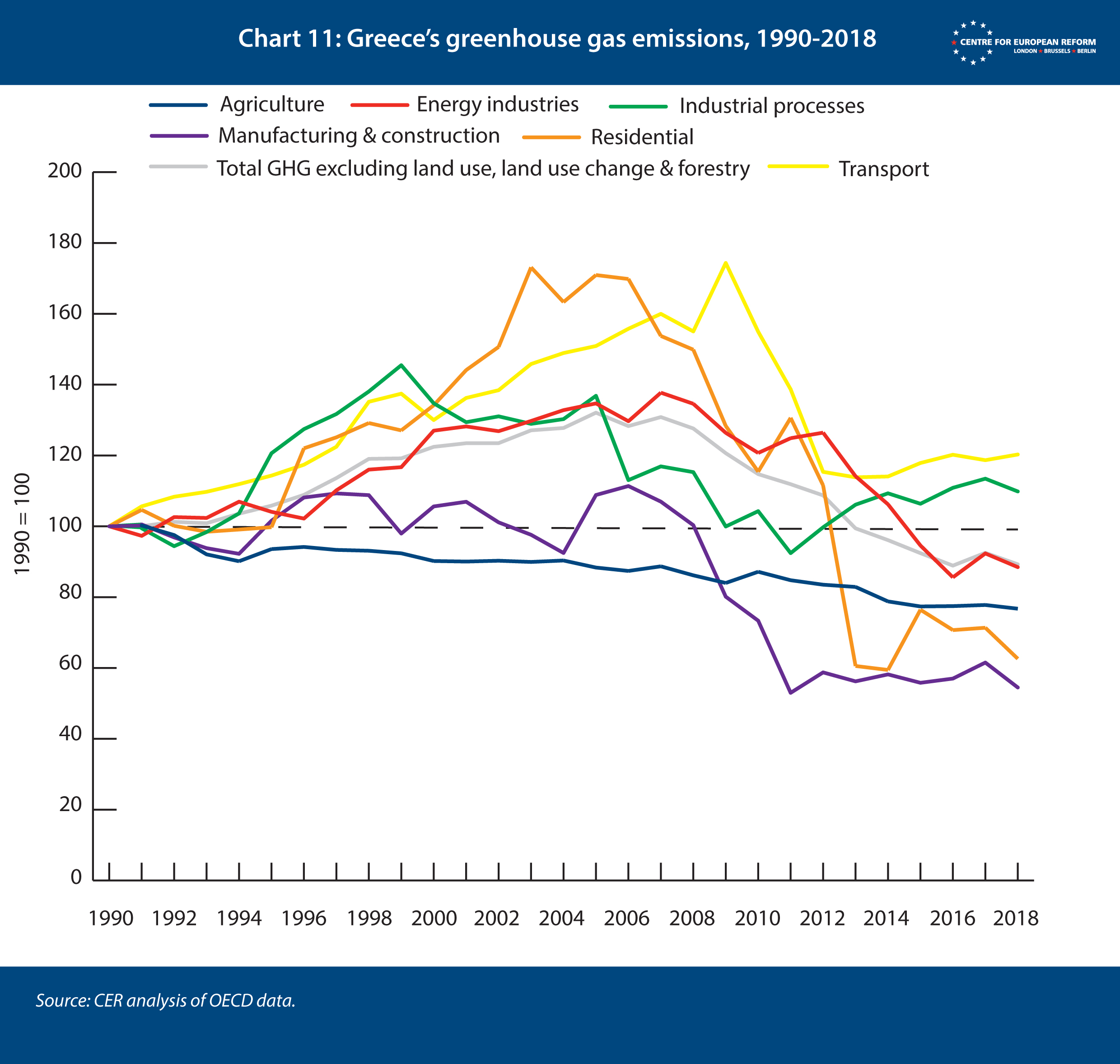

While Greece’s total greenhouse gas emissions fell by 11 per cent between 1990 and 2018, this was largely due to the economic depression of the 2010s (Chart 11). Transport emissions have increased by 20 per cent since 1990, though they are lower today than their pre-financial crisis peak. Manufacturing emissions have dropped by 45 per cent, mainly due to the slump. And emissions from energy industries and housing have fallen as the crisis curbed energy demand.

Coal constituted 38 per cent of total energy supply in 1990, but its share in 2019 had fallen to 15 per cent, having been largely replaced by natural gas and renewable energy. The Greek power sector’s carbon intensity (measured in CO2 emissions per kWh of heat and power) remains substantially higher than the OECD average, but it dropped by 26 per cent between 2005 and 2015 as coal and oil-fired generation fell.5 Greece exceeded its 2020 renewable energy target and it has announced that it will phase out lignite coal by 2028.6

Greece’s recovery plan

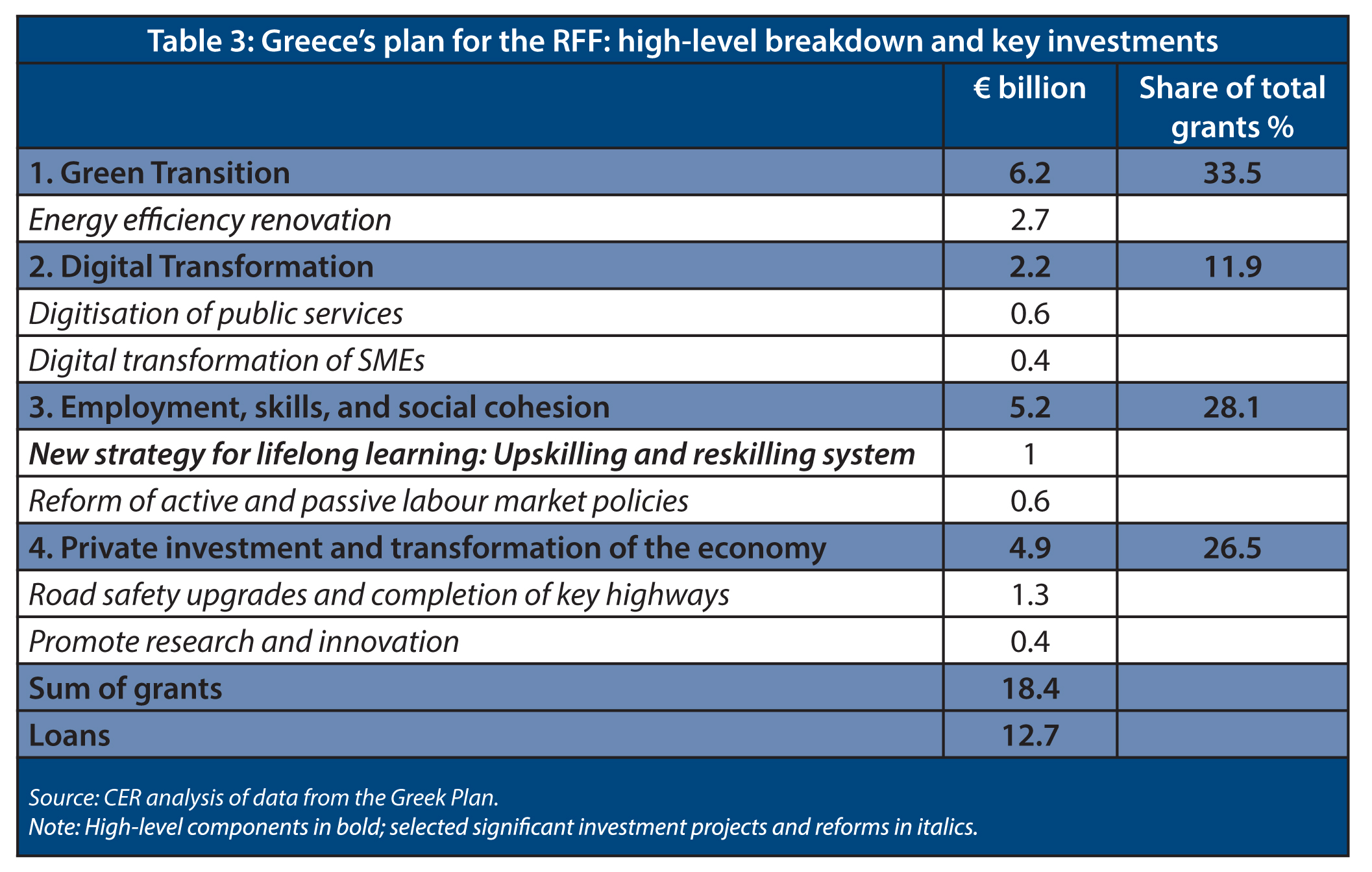

Greece is framing its recovery plan as a strategy to rebound from the COVID-19 crisis, and also to change the Greek growth model and institutions. For this reason, it is reform-heavy and plans to deploy both grants and loans from the RRF – respectively €18.5 and €12.7 billion – between 2021 and 2026. Investment and reforms cover four priorities: the green transition; the digital transformation; employment, skills and social cohesion; private investment and the transformation of the economy.

Energy efficiency renovations make up the largest investment – €2.7 billion – under the green transition heading – mainly in residential buildings, but the plan will also insulate public buildings and provide incentives for private businesses to do the same. Importantly, such investments are paired with the development of an energy poverty action plan, to provide financial support for households unable to heat their homes adequately (currently estimated at 18 per cent of the population).7

Other projects include making water management more efficient, by addressing water supply and irrigation, and improving and expanding wastewater treatment. On the climate resilience front, the plan also includes investments for reforestation, flood mitigation and forest firefighting.

Power sector investment focuses on expanding storage (€450 million) and strengthening the transmission and distribution system, to enable greater penetration of intermittent renewable energy. The plan will also finance the first carbon capture and storage facility in Greece.

The plan devotes about €550 million to electric transport, including the installation of over 6,600 electric vehicle chargers, but also support to e-mobility industries (such as electric car manufacturing and battery recycling). Road transport absorbs a sizeable chunk of funds devoted to ‘transformation of the economy’: road safety upgrades and the completion of multiple highways will be given €1.3 billion. While these are critical infrastructure, by comparison, only €211 million is devoted to improving cross-country and suburban railways.

As with most countries’ plans, digitisation investments are sizeable, with the most generous being €580 million for digitising public sector archives and services, followed by support for digital upgrades in SMEs (€375 million) and in schools. Digital infrastructure – 5G, broadband, submarine cables – receives €320 million. The government will give tax credits to SMEs investing in digital technology and in equipment for climate change adaptation and the circular economy.

In employment, skills and social cohesion, much of the plan is devoted to structural reforms. This includes €640 million for the reform of labour market policies, including an improvement in the coverage and distribution of unemployment benefits, and programmes that subsidise businesses to employ the unemployed. Over €1 billion is assigned to a new strategy for lifelong learning. Healthcare absorbs about €1.5 billion, involving upgrades of hospital infrastructure and investments in preventative public health programmes, as well as reforms of primary healthcare and the establishment of a home healthcare system. Some of the most ambitious reforms aim to make the justice system and the public administration more efficient, and to boost tax collection.

2: OECD, ‘Economic Outlook’, May 2021.

3: OECD, ‘Economic survey of Greece’, July 2020.

4: Bank of Greece, ‘Summary of the annual report’, March 2020.

5: International Energy Agency, ‘Greece 2017 review’, Energy policies of IEA countries, 2017.

6: OECD, ‘Greece 2020’, OECD Environmental Performance Reviews, October 2020.

7: ‘Greece 2.0. National Recovery and Resilience Plan.’, May 2021.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2021

This paper is published in partnership with the Open Society European Policy Institute.

View press release

Download full publication