Why the EU's recovery fund should be permanent: Country report - Spain

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Spain

As of July 2021, Spain had suffered over 81,000 confirmed deaths, with its worst wave in January 2021.1 Lockdowns were put in place in March-June 2020 and in October 2020-May 2021. This took a toll on economic activity, as GDP dropped by 10.8 per cent and unemployment climbed to 15.5 per cent in 2020.2

The government’s emergency fiscal measures totalled €85 billion as of June 2021, with €24.7 billion being devoted to unemployment benefits for temporarily laid-off workers (Temporary Employment Adjustment Schemes, or ERTEs).3 An additional €100 billion was devoted to government guarantees for loans taken up by firms and self-employed workers.

As of September 2021, over 80 per cent of the population had received at least one shot of the COVID-19 vaccine.4 The Banco de España, Spain’s central bank, forecasts 6.2 per cent GDP growth in 2021, with economic activity reaching pre-pandemic levels in late 2022.5

Long-term economic performance

While Spain’s post-financial crisis unemployment rate had peaked at 26 per cent in 2013, it was still at 14 per cent in 2019 – substantially higher than the eurozone average.6 As a result of high levels of protection for workers on permanent contracts, 25 per cent of the employed workforce has temporary contracts, over ten percentage points higher than the eurozone average.7 Many people on temporary contracts lost their jobs in the pandemic.

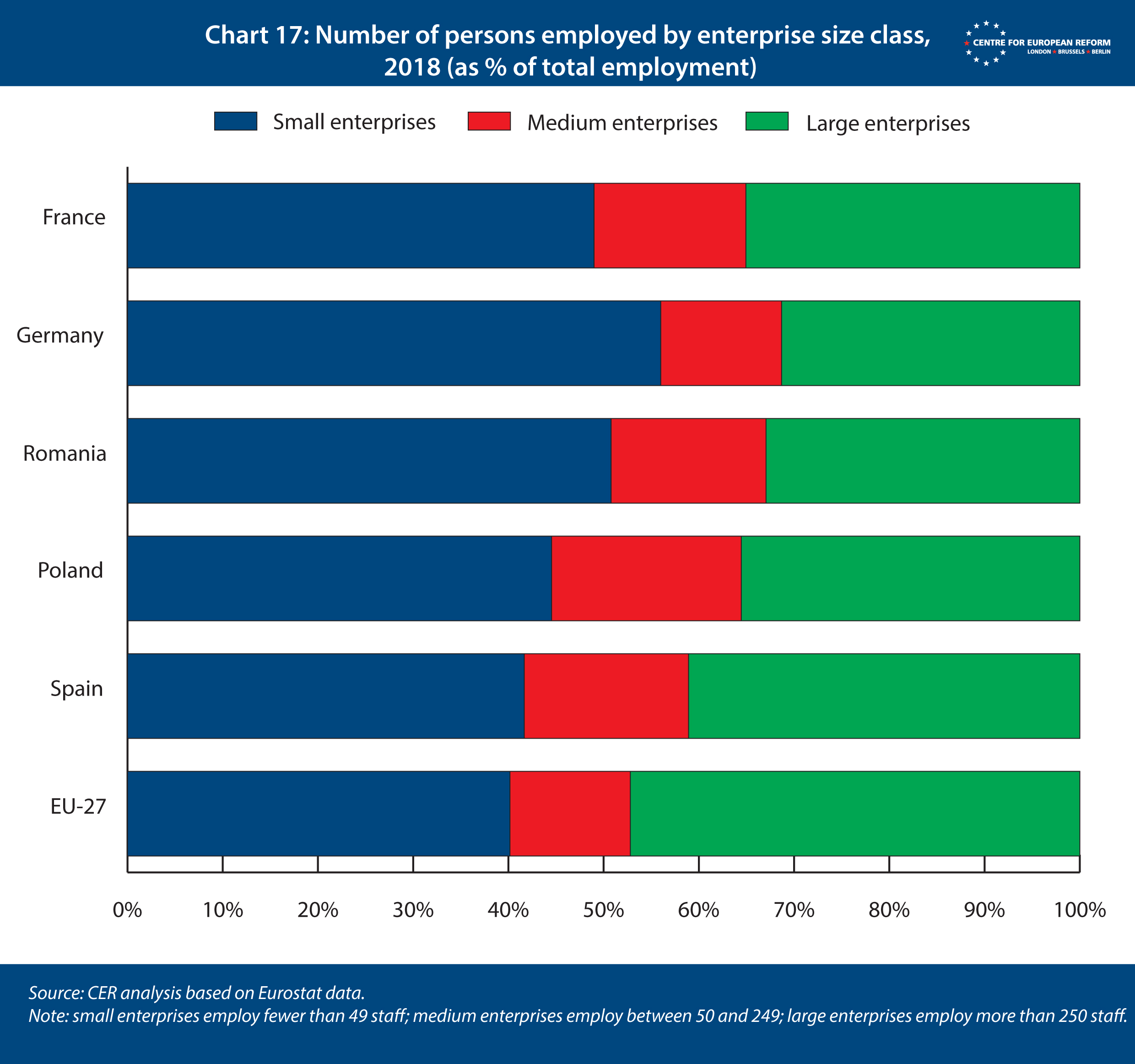

The Banco de España blames the small size of Spanish firms (see Chart 17) and relatively low skills and technological capital as the main reasons for low economic growth in Spain. Spain’s central bank argued that the government needs to redesign the education system, and raise investment in innovation.8

Greenhouse gas emissions

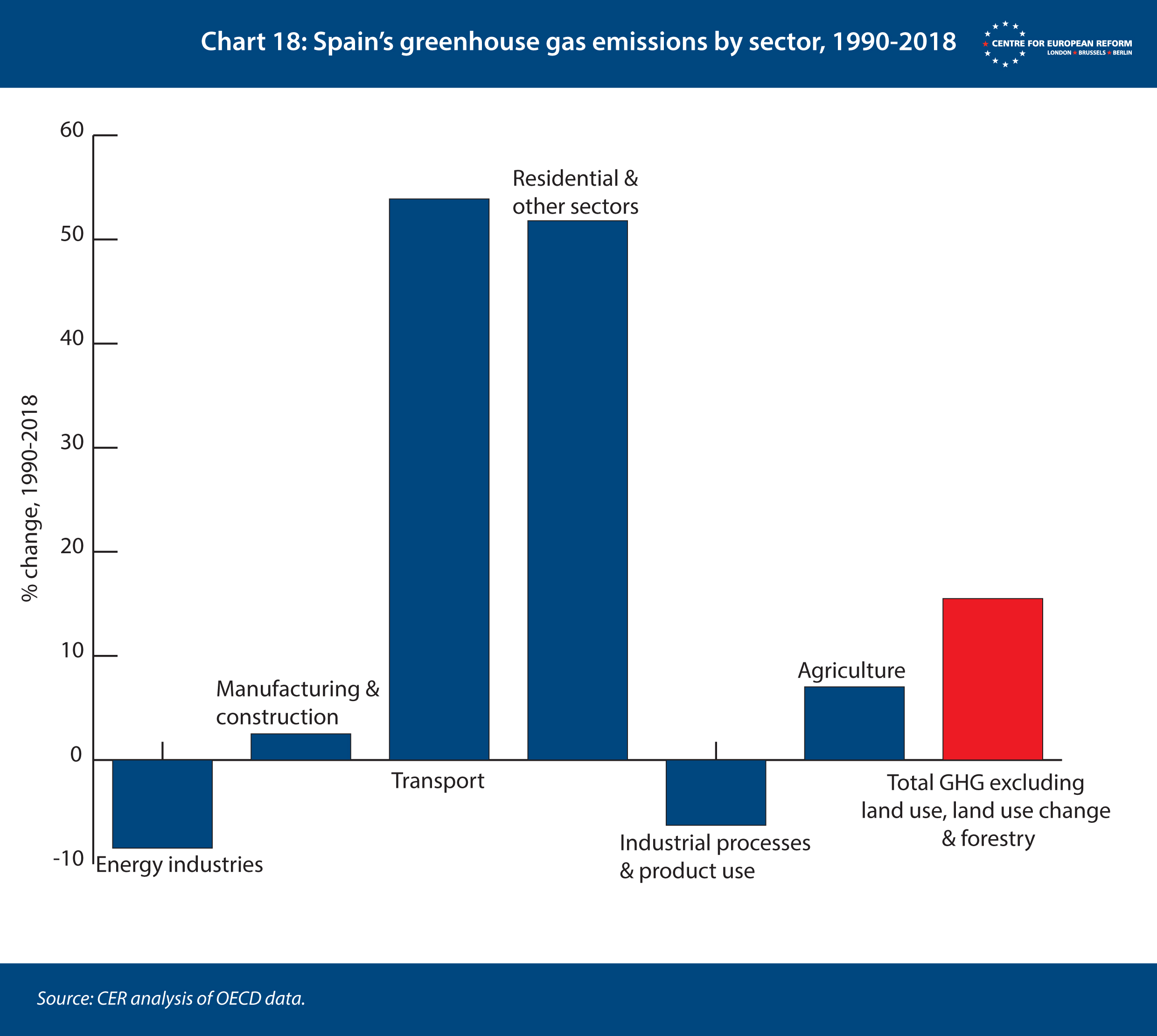

Spain’s greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 16 per cent since 1990 (see Chart 18). However, emissions peaked in 2007 and have since been falling, allowing Spain to meet its 2020 target.9 Per capita emissions, at 7.1 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (tCO2eq) in 2018, are lower than the EU average of 8.2 tCO2eq.10

Most emission cuts have come from the energy sector, whereas emissions in the transport and residential sectors have increased by over 50 per cent since 1990.11 In 2019, Spain met 18.4 per cent of total energy consumption with renewable energy, and it aims to increase this share to 42 per cent by 2030. Renewable energy should generate 74 per cent of electricity generation by then.12

Spain’s recovery plan

Spain plans to invest about €70 billion in grants from the RRF between 2021 and 2023, covering four broad priority areas: green transition, digital transformation, social and territorial cohesion, and gender equality: this assessment focuses on this early set of investments. An additional €70 billion in RRF loans will be used to finance special funds in 2021-2023 (for example supporting business recapitalisation and scaling start-ups), and the continuation of investment programmes beyond 2023.

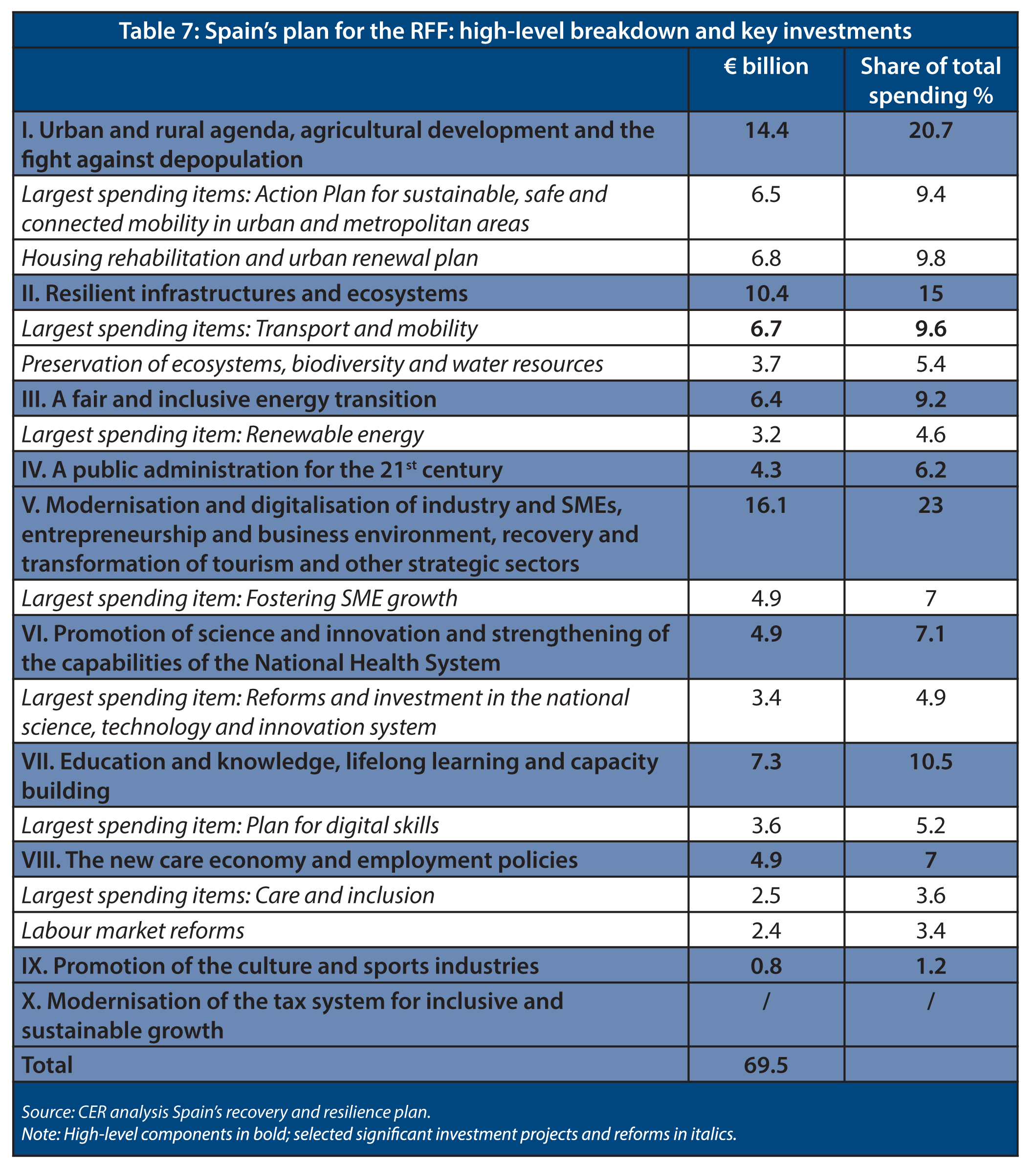

Spain’s plan groups investments and reforms into ten ‘lever policies’ (see Table 7). The result is a very reform-intensive plan. The overhaul of the fiscal system and public administration are the two most important sets of reforms.

As for investment, the area receiving most money is the modernisation and digitisation of industry and SMEs, with €16 billion, amounting to 23 per cent of funds. Sector-specific efforts include a focus on modernising key sectors – tourism, automotive, agri-food, health, aviation, shipping and renewables. Some of the funds also aim to support more niche innovations, such as 3D printing.

Green investments target sustainable mobility (both national and local infrastructure and the renewal of vehicle fleets), housing renovations and energy infrastructure. Smaller investments seek to protect and restore ecosystems and water resources.

While subsidies for electric cars are included, the sustainable mobility chapter of the plan (€6.5 billion) focuses on alternatives to the use of private vehicles such as cycling, walking and public transport, in an effort to improve air quality. The government has put forward housing renovation and urban renewal plans, with a focus on lower-income areas. This is a clever effort to deal with energy poverty in lower-income areas while improving economic and social conditions.

Support for renewable energy focuses on innovative sources and specific applications, such as integrating renewable energy generation with buildings, businesses and industry, and installing renewable plants on islands. Energy sector investment is also oriented towards storage and smart grids, highlighting their role in the clean energy transition.

Spain is investing €12.3 billion in education, skills and research, encompassing virtually all stages of education including lifelong learning. The biggest investment is a national plan for digital skills, which aims to create a network of centres for digital skills training, catering to both students and workers. A reform of vocational training aims to improve the skills of both employed and unemployed citizens. On research, the plan aims to improve governance and co-ordination within the system of public institutions focusing on science, technology and innovation, and to strengthen the connection between public R&D institutions and the private sector.

On social policy, the €4.9 billion budget is almost evenly split between care and inclusion, including reforms of social services and asylum, and employment. While employment-oriented measures aim to reduce the excessive reliance on temporary contracts, and increase particularly youth and female employment, relatively few details are provided on the strategies and investments to achieve this.

2: OECD, ‘Spain Economic Snapshot’, consulted in June 2021.

3: International Monetary Fund, ‘Policy responses to COVID-19’, website last updated on July 2nd 2021.

4: Our World in Data, Covid-19 dataset.

5: Banco de España, ‘Proyecciones macroeconómicas de la economía española (2021-2023)’, Boletín Económico 2/2021.

6: International Labour Organisation, ILOSTAT database. Data retrieved on September 7th 2021.

7: Banco de España, ‘Informe anual 2020’, May 2021.

8: Banco de España, ‘Informe anual 2019’, June 2020.

9: OECD statistics, Greenhouse gas emissions data: National Inventory Submissions 2021 to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, CRF tables), and replies to the OECD State of the Environment Questionnaire.

10: Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico, ‘Environmental Profile of Spain 2019’, 2020.

11: OECD statistics, Greenhouse gas emissions data: National Inventory Submissions 2021 to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, CRF tables), and replies to the OECD State of the Environment Questionnaire.

12: Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y et Reto Demografico, ‘Environmental Profile of Spain 2019’, 2020.

Elisabetta Cornago is a research fellow and John Springford is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform

November 2021

This paper is published in partnership with the Open Society European Policy Institute.

View press release

Download full publication